Dr Johnson’s definition of the essay -- a loose sally of the mind -- admirably describes the eighteenth century essay. A loose sally can expound tedious homilies, political beliefs, whimsical fancies, domestic brawls, lampooning established notions, self-righteous treaties, and almost anything under the sun. It is difficult to draw a line of demarcation in the genre known as the essay. An essay is noteworthy only if the essayist has the sensitivity to express a critical taste which is devoid of pedantry and vulgarity.

Of the prominent eighteenth century essayists, I find Pope’s work to be singularly devoid of humour. And when it comes to writing long sentences there are not many who can match him.

"The prostitution of praise is not only a receipt upon the gross of mankind, who take their notion of characters from the learned; but also the better sort must by this means lose some part at least of that desire of fame is the incentive to generous actions, when they find it promiscuously bestowed on the merriment and undertaking; nay, the author himself, let him be supposed to have ever so true a value for the patron, can find no terms to express it, but what have been already used and rendered suspected by flatterers."

Oscar Wilde was not enamoured of Pope’s poetry, and from what little I have read of his prose I cannot say that I have been enthralled.

*****

Philip Stanhope, the Earl of Chesterfield, also wrote essays but his fame rests on the letters he wrote to his son on the art of becoming a man of the world and a gentleman ("I would heartily wish that you may often be seen to smile but never heard to laugh while you live.") He was also a protector of men of letters. He was Johnson’s patron when Johnson began his monumental work on his Dictionary of the English language. After seven years of intensely hard work Johnson requested him for some financial help. The Earl flatly turned down the request which prompted Johnson to write his famous rebuke: "Is not a patron, my Lord, one who looks upon with unconcern on a man struggling in the water and when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help?"

It may not be out of place to mention that on the publication of Chesterfield’s letters, Johnson said that "they teach the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing master."

*****

In the middle of the eighteenth century the Rambler made its appearance. It was natural that after the Tatler and the Spectator had fallen into oblivion, a new journal would emerge to try and do for the Georgian era what its predecessor had done for the reign of Queen Anne.

As a conversationalist -- if you know your Boswell -- Dr Johnson has a "fund of generous wit". As a letter-writer he wields a trenchant style. In his essays his humour comes across even when he overwhelms us with words:

"… he that upon level ground stagnates in silence, or creeps in narrative, might, at the height of half a mile, ferment with merriment, sparkle with repartee and froth with declamation."

But when it comes to pricking the pomposity of a charlatan, his wit has all the irony:

"Dick Minim a self-styled critic who is wielding such power that he has his own seat in the coffee-house. He is admitted to rehearsals and many of his friends are of opinion that our present dramatists are indebted to him for his happiest thoughts.

He is the greatest investigator of hidden beauties and is particularly delighted when he finds the sound an echo to the sense. He wonders at the supineness with which their works have been hitherto perused, and that the wonderful lines about honour and a bubble, have hitherto passed without notice:

‘Honour is like a glassy bubble

Which costs philosophers such trouble

Where one part crack’d the whole does fly,

And wits are crack’d to find out why’

In these verses, says Minim, we have two striking accommodations of the sound to the sense. It is impossible to utter the two lines emphatically without an act like that which they describe, bubble and trouble causing momentary inflation of the cheeks by the retention of the breath, which is afterwards forcibly emitted, as in the practice of blowing bubbles…."

* * * * * *

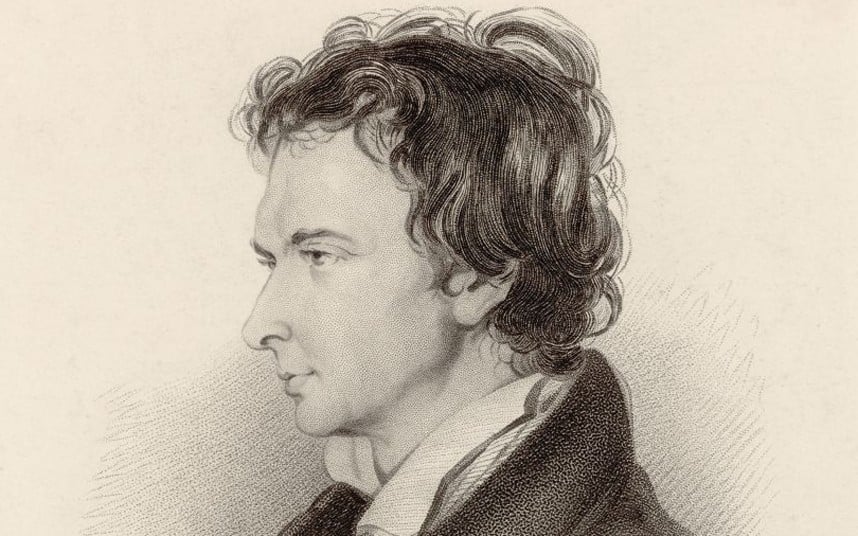

In Hazlitt’s essays -- this not to say that I am unmindful of Goldsmith and Leigh Hunt and Lamb -- a different spirit is apparent. As an essayist, his style is exuberant. He approaches his subject with originality and freshness. It was said of him by the critics of his time that Hazlitt’s taste "was not the creature of schools and canons, it was-begotten of Enthusiasm of Thought." "My Sun" he wrote "arose with the first dawn of liberty." After Addison, I prefer to read Hazlitt’s essays more than anyone else’s.

"One of the pleasantest things in the world is going a journey. I can enjoy society in a room: but out of doors nature is company enough for me. I am then never less alone than when I am alone.

I cannot see the wit of walking and talking at the same time. When I am in the country, I wish to vegetate like the country. I am not for criticizing hedgerows and cattle. I go out of town in order to forget the town and all that is in it. There are those who for this purpose go to watering-places, and carry the metropolis with them. I like more elbow-room and fewer encumbrances. I like solitude when I give myself up to it, I like solitude when I give myself up to it for the sake of solitude, nor do I ask for …………………………………..

‘a friend in my

retreat

when I may whisper, solitude is

sweet.’

Give me the clear blue sky over my head and the green turf between my feet, winding road before me, and a three hour march to dinner -- and then to thinking! It is hard if I cannot start some game on these lone heaths. I laugh, I run, I leap, I sing, for joy. Instead of awkward silence, broken by attempts at wit or dull commonplaces, mine is that undisturbed silence of the heart which alone is perfect eloquence.

*****

The essay in the eighteenth century traced the human life through all its mazes and one of the greatest services it did to English literature was to give impetus to writers like Richardson and Fielding who then lit the torch of the novel. In many ways the essay led the way to the perfecting of the novel which then ruled the nineteenth century.

(concluded)