In order to understand the societal trends that justify and perpetrate violence, George Orwell’s novel 1984, albeit set up in a completely different context than Pakistan’s, reveals some interesting comparisons

With the growing incidents of violence in Pakistan, there have been corresponding efforts to promote peace. Most of these efforts are conceived in the form of funded projects and are bound in logframes or theories of change, therefore the conceivers and designers of such initiatives are constantly grappling within the frameworks of problem trees, problem statements and identification of root causes to what leads to violence.

Often the focus seems to fall on poverty, inequality, increasing religious extremism on account of growing number of madrassahs etc.

But terrorism and organised crime should not be seen as the only forms of violence while we try to deal with the issue of peace and conflict. How violence is perceived and received at societal level reflects the collective consciousness and is perhaps the missing link in the analysis of violence, peace and conflict.

In the case of Pakistan, we witness a range of responses varying from lukewarm conditional rejections; justification and at times, even glorification of acts of violence and their perpetrators. Hostility towards the victim by putting the blame on him/her is also not that uncommon especially when a conspiracy theory related to religion is weaved around the victim’s plight.

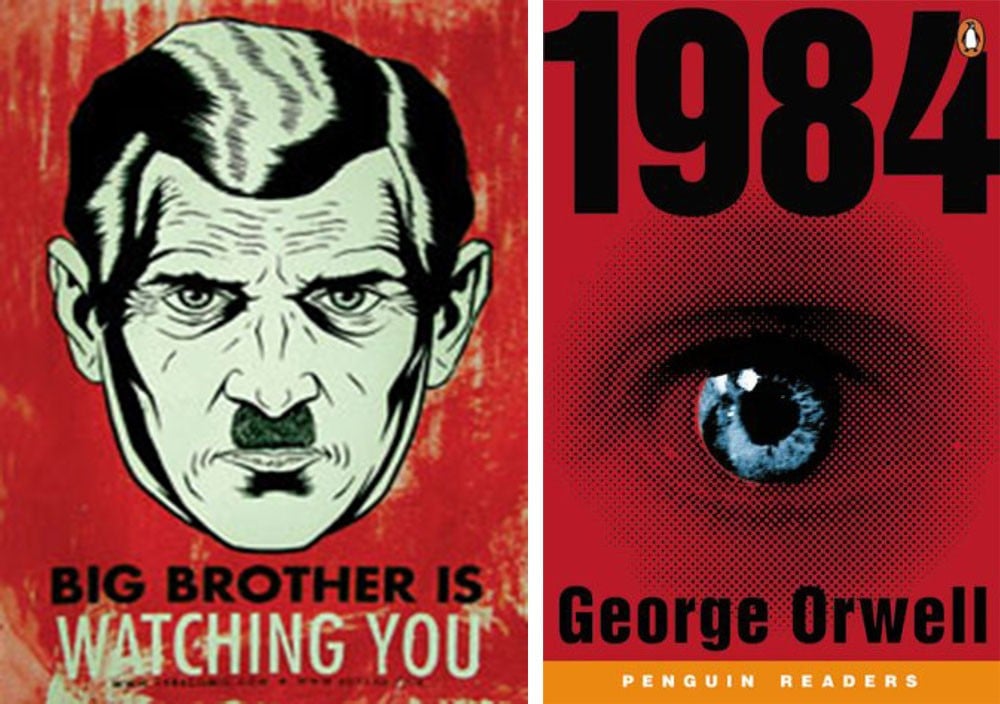

Incidents of mob violence, which is a manifestation of undirected anger wherein many participants do not even know or care for the reason why the violence was instigated, is also seen. In order to understand the societal trends that justify and perpetrate violence, George Orwell’s novel 1984, albeit set up in a completely different context than Pakistan’s, reveals some interesting comparisons.

The novel depicts the totalitarian regime of the Big Brother -- the leader of a political party of the revolutionists. The citizens of Oceania are grilled 24/7 to construct an absolute identity which is the only right identity -- a loyalist to the regime, a blind unquestioning patriot devoid of critical thinking.

The party is equivalent only to everything that represents the Big Brother and his army. Therefore, any dissent to this identity is presented in terms of disloyalty to the party which is tantamount to disloyalty to the country. To maintain the singularity of this identity, hatred and suspicion against an abstract notion of enemy -- an Other is nurtured. The image of the enemy is flexible enough to cover any form of dissent.

Other than the formal regulatory institutions like the Thought Police, each and every individual is trained to identify signs of traitors and blow the whistle. Children happen to become the best whistle blowers -- the most eager of volunteer regulators. There is a telescreen in every home that keeps on eulogising the Big Brother and transmitting messages of hate continuously.

For the citizens of Oceania, even the sense of pleasure is checked and curtailed: ‘Victory Gin’ is a ‘colourless liquid’ that tastes like nitric acid; chocolate is rationed and it is the ‘Party’s undeclared purpose to remove all pleasure from the sexual act’.

In this atmosphere of fear, suppression, hatred and suspicion, George Orwell shows the troubling acceptance of violence at societal level.

While watching a war movie, the scene of a man being shot while trying to escape the collapsing ship of refugees bombed by police provokes a roar of amused laughter from the audience. The hate speech is supposed to arouse the feelings of hatred towards the enemy of the party. "But the rage that one felt was an abstract, undirected emotion which could be switched from one object to another like the flame of a blowlamp. It was even possible, at moments, to switch one’s hatred this way or that by a voluntary act."

Pakistan also had its 1984 starting from 1977 when Big Brother’s Pakistani counterpart -- General Ziaul Haq -- overthrew the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and imposed martial law. The state-run television and radio served the purpose of the telescreen, hammering into the heads of the hapless hoodwinked people how the usurpers were the rescuers, the saviours of the country; and how thinking otherwise was a treason not only against the country but also blasphemous because Pakistan under Zia was synonymous to Islam.

Histrocially, the need of an ever-present enemy was supplemented by India and Hindu; but opposed to the rigidity of the enforced singular identity based on religion, there was an ambiguity and hence flexibility in the definition of enemy. The primary focus through the lens of faith meant that anyone who digressed from it or was perceived to digress from it was also deemed to be an enemy, hence any heretic, kaafir or a munafiq or a blasphemer were equally big enemies.

Thought policing controlled not just free thinking but also the experience of pleasure. The sensuous songs of Noor Jehan were chastised by Pakistan Television; performers like Nazia and Zohaib Hassan, persecuted on the charge of indecency; modesty and chastity became the most aspired targets for young women. The generation that was growing up at that time, just like in Orwell’s novel became the most vigilant guardians of that order and all that it stood for.

The sense of fear, insecurity, persecution, control and hatred against the enemy coupled with an unquestioning self-righteousness is what constitutes the psyche of the children growing up under ‘Islamised Pakistan’. It manifests in the tendencies whereby violence is not just justifiable but also glorified if carried out in the name of a sanctimonious cause. Mob lynching of accused blasphemers is reminiscent of Orwell’s undirected sense of cultivated hatred.

Keeping this background in mind, we could assume that efforts to uproot the causes of violence at policy and legal levels are bound to come to nought unless the societal effects of decade-long protracted venomous proselytisation are taken into account.

"Killing a man before killing the idea will only reincarnate him in a hundred avatars", tweeted Dr Asif Iftikhar (Fellow, al-Mawrid; visiting faculty LUMS) at the huge uproar witnessed at Mumtaz Qadri’s hanging. If our policy and decision makers fail to check and redress the real causes that abet and fuel violence, the problem tree bound projects would keep on leading to impartial solutions. Misleading binaries that minds are trained to believe like ‘War is Peace’ from Orwell’s novel would only be reversed when the costs of the ideals we are taught to worship are paid by our own blood; and when distant glory becomes imminent threat.

Hence we see mourning parents wonder how their innocent school going children turn into unwilling martyrs of a cause. Unfortunately, this might imply more violence before things turn for better. Can we do something to unlearn thought policing at individual and societal levels? The readiness to respond to this question will determine the future of peace in this country.