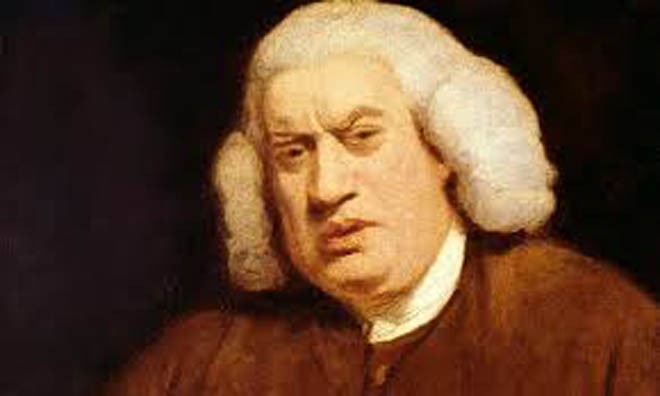

What is an essay? No one has described it better than Dr Johnson: "A loose sally of the mind; an irregular, indigested piece; not a regular and orderly composition."

An essay can be a short, discursive article on any literary, philosophical or social subject viewed from a personal or historical standpoint; or it can be a dissertation on the values of a society. The range of subjects for an essay is unlimited.

The rise of the English essay coincides with the decline of the stage in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Artificial comedy, the characteristic product of the Restoration age, had begun to reel under the onset of writers like Dryden and Steele.

Dryden is usually credited with having given modernism to English prose. Since he is also considered to be the founder of literary criticism, Dryden is regarded to be one of the pioneers of the essay, if only because he wrote in a colloquial style intended to appeal not to a small circle of the literati, but to a wider and more popular audience.

It is an interesting historical fact that the essay is closely linked with the history of clubs and coffee houses in London. Professor Lobban, in his study of the essay, writes that, "it was eminently natural for the early essayists, when they were on the outlook for a simple device, to avail themselves of this predominating feature."

The literary taste of London at the turn of the eighteenth century was almost entirely directed by the chief coffee house intellectuals. Most of the literary criticism that I have read suggests that the first half of the eighteenth century witnessed a vast improvement in the manner and customs of English society in effecting which the essay was not the least powerful factor. The popular doggerel of the time was:

"You may see what fashions are

How periwigs are curled

And for a penny you may hear

All novels in the world."

The high priest of the eighteenth century literati, Dr Samuel Johnson, thought that the English essay was the product of French and Italian influences. Later scholars believed that the only obligation the English essay owes to foreign influence is the essays of Montaigne. Dryden, who wrote before Johnson, admits that he learned the rambling style of a preface from Montaigne. Dryden, made a bold inroad into the stiffness of Elizabethan prose.

A large change had taken place in the nature of social life when Queen Anne ascended the throne of England at the very start of the eighteenth century. A new form of literature was needed to gratify the cravings of Queen Anne Society. It was the work of essay to supply the demand.

The first regular daily newspaper appeared within days of Queen Anne’s ascension. A couple of years later Daniel Defoe’s Review came out, followed by the tri-weekly Tatler. These newspapers greatly influenced the growth of the essay. The Review, for instance, not only invented the concept of the leading article, but also published fearless criticism of the topics of the day. After the Review, it was the Tatler that produced the transition from journalism to essay writing. Then came the Spectator, the famous periodical under the editorship of Addison and Steele.

* * * * *

When we think of the English essay we think of the eighteenth century and luminous names like Defoe, Swift, Pope, Johnson, Lamb, Hazlitt and, of course, Addison and Steele. I feel amused to remember that in my college days the weekly hour marked for English essay was referred to as ‘Addison and Steele’.

If the Tatler was the journal that produced the transition from journalism to essay, the Spectator was the periodical that gave maturity to the essay itself. Steele was the first writer to make the essay an instrument for exhibiting contemporary manners.

Of the two, Addison had the more important share in the partnership not because of his literary prowess and his superior grasp of the classics, but because of his sense of humour. Addison’s humour is tinged with irony and it had nearly always a certain solemnity which makes it all the more poignant. Addison’s chief merit lies in the power of his satire. According to the critic Lobban, "Irony in his hands, was like a fine rapier which can wound without at once being felt and no English writer has excelled him in the deft handling of the weapon." Here are some passages from his article, ‘The Tory Fox-hunter’:

"I was travelling towards one of the remote parts of England when about three o’clock in the afternoon, seeing a country gentleman trotting before me with a spaniel by his horse’s side, I made up to him. Our conversation opened about the weather in which we were very unanimous, having both agreed that it was too dry for the season of the year. My fellow traveller upon this observed to me that there had been no great weather since the Revolution. I was a little startled at so extraordinary a remark but would not interrupt him till he proceeded to tell me of the fine weather they used to have in King Charles the Second’s reign. I only answered that I did not see how the badness of the weather would be the king’s fault….

Supper was no sooner served in than he declared that he had always been against all treaties and alliances with foreigners. I took this occasion to insinuate the advantages of trade by observing to him that the lemons, the brandy the sugar, and the nutmeg were all foreigners. This put him into confusion, but the landlord, who overheard me, brought him off by affirming that for constant use, there was no liquor like a cup of English water provided it had malt enough in it.

My squire laughed hearty at this and made the landlord sit down with us. We sat pretty late over our punch and drank the health of several persons in the country whom I had never heard of, that they assured me were the ablest statesmen in the country, and of some Londoners whom they extolled to the skies for their wit, and who, I knew, pass in town for silly fellows. It being now midnight, he shook me very heartily by the hand at parling, and discovered a great air of satisfaction in his looks that he had met with an opportunity of showing his parts and left me a much wiser man than he found me…"

You cannot help admire the delicacy of Addison’s portraiture and the lightness of touch… the writing is all the more incisive because many such Tories (fox-hunters or not) still exist. One has only to look at Osbert Lancaster’s cartoons.

(to be continued)