Pakistan should release Indian national Hamid Ansari who has already spent more than three years in detention -- and the young journalist Zeenat Shehzadi who was trying to help him

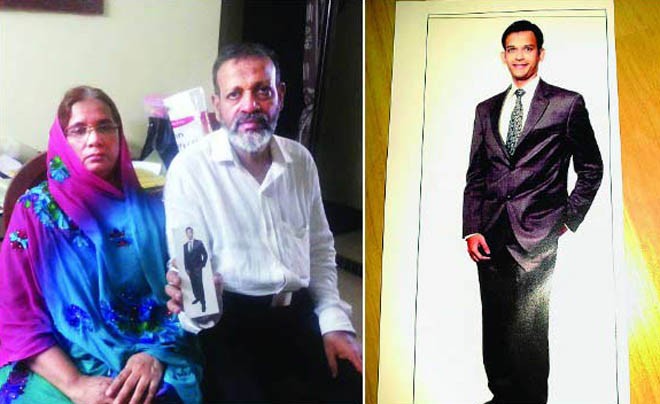

The anguish in Fauzia Ansari’s voice is palpable as we speak over the phone. She has not seen her son since he went missing on November 2012. The good news? At least now she knows where he is: Peshawar Central Jail, sentenced by a military court to three years imprisonment.

"At the time of his arrest, the only charge that could be brought against him was that he had illegally entered Pakistan. The maximum punishment for that offence is six months and Hamid’s detention period has already exceeded three years," writes I.A. Rehman, the respected journalist and Director of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.

So why is Hamid, a 26-year old Rotarian and MBA graduate who taught at the Mumbai Management College, in prison in Pakistan? One reason is that he is an Indian foolish enough to enter Pakistan without a visa.

Why he did that becomes apparent from hundreds of chat messages on Facebook that his parents, Nehal, a bank employee, and Fauzia, a college teacher, found going through his computer after he disappeared. He had not signed out of the account.

The chats reveal that Hamid was emotionally involved with a young woman in Kohat who disappeared from Facebook after telling him that her father was getting her married off. Hamid contacted other Facebook friends in Pakistan.

Some of them encouraged him to bypass the visa process -- even though he had a letter of invitation from the Rotary Governor in Peshawar. Instead, he followed the plan his Facebook friends had outlined for him, explaining how to cross over from Afghanistan into Pakistan at the Torkham Pass.

Telling his parents that he had a job interview in Kabul, he flew out from Mumbai on Nov 4, 2012.

His parents know the names of his ‘friends’ as well as the hotel he stayed at in Kohat for two nights before he disappeared. But they knew no one in Pakistan who would follow up these leads.

Based on what they found, they believe that their son was trapped into the course of action he took.

Of course that he was wrong to do so, as Fauzia admits in the mercy appeal she has recently sent to Pakistan’s president, prime minister, chief justice and Army chief.

Her appeal pleads for the period of punishment to be set off against the time Hamid has already been incarcerated. She shouldn’t have to ask this. International law requires it.

The distraught parents even approached the Supreme Court of India to get the Indian government to pursue the case with Pakistan. In February 2014, the court disposed of the petition, saying there was little the Indian government and even less the court could do.

The honourable court could have referred to an earlier judgment of 2012, when a two-member bench including Justice Markandey Katju had appealed to Pakistan in humanity’s name to release Indian prisoner Gopal Das. The judgement quoted a verse by Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Shakespeare’s famous ‘quality of mercy" speech from The Merchant of Venice. Then President Zardari had commuted the remainder of Das’ sentence, returning him to India earlier.

That Fauzia Ansari still doesn’t have a copy of the judgment sentencing her son speaks volumes for the chasm and difficulty of communication between the two countries.

Even those who help may find themselves in trouble, like freelance journalist in Lahore, Zeenat Shehzadi who was working on Hamid’s case.

A young woman from a modest background, passionate about human rights and freedom of information, Zeenat had obtained Fauzia’s number and reached her while the Ansaris were on pilgrimage in Mecca, about a year after Hamid’s disappearance.

To Fauzia, it was literally like an answer to her prayers.

"Zeenat told me that she would do what she could to help -- but not if Hamid had done anything wrong against her country," Fauzia told me over the phone from Mumbai. "I felt an angel had been sent to help me."

When she told Zeenat that she had been weeping and praying for help at the time of the call, Zeenat too was moved.

Fauzia sent Zeenat all the information she had. Satisfied that Hamid’s only wrongdoing was illegal border crossing, Zeenat agreed to help. Fauzia gave her power of attorney to pursue Hamid’s case, and occasionally sent money via a relative in Dubai to cover her expenses.

Thanks largely to Zeenat’s efforts, the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances looking into cases related to some 25 missing persons included Indian national Hamid Nehal Ansari in its list.

But since the morning of August 19, 2015, Zeenat too has gone missing. Some men in a white car (why is it always a white car?) picked her up from a bus stop near her house in Lahore. She was to appear before the Commission on Aug 24, 2015.

She had received a warning earlier after meeting the Indian high commissioner at a public event in Lahore on August 12, 2015. Plainclothes men had detained her and interrogated her for several hours. They let her go with a warning to not pursue Hamid Ansari’s case. She was shaken when she reached home but determined to pursue the cause of justice, says her younger brother Salman Lateef, 22. She told her family not to worry if anything happened to her, but of course they have been worried sick (literally) since her disappearance six months ago.

Her family managed to register an FIR at the Nishtar town police station, Lahore, with SHO Asif (FIR no. 1080).

"Zeenat is my priority," Fauzia told me when we spoke. "I feel responsible for her disappearance. She is in this situation because she was trying to help me. I wish she could be back home before Hamid."

It was Zeenat who showed Fauzia how to use Facebook and made a Facebook page for Hamid Nehal Ansari. It has not been updated since her disappearance.

Fauzia says that she and Zeenat talked often. "If she didn’t hear from me for 2-3 days, she’d ask if I was upset. When I had a bad accident, she told me to drink warm milk with turmeric," she adds. "She really became like the daughter I never had."

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances has set up a joint investigation team (JIT) to trace Zeenat and recorded some evidence, including eyewitnesses who saw Zeenat being taken away. Police have traced the vehicle, (HK 286) to an individual in Islamabad but express their inability to do more.

Police and security agency representatives in each JIT meeting refuse to confirm or deny that Zeenat is in their custody. Nor are they making any moves to recover her.

In Hamid’s case, there is room for optimism. The Pakistan High Commission in Delhi has forwarded Fauzia’s appeal to the President and other. The Indian High Commission in Islamabad has requested access to the prisoner that Pakistan is likely to grant. Fauzia’s appeal for a visa to visit Pakistan will probably be granted "on humanitarian grounds" -- she doesn’t have a sponsor in Pakistan that the visa protocol requires.

Had Hamid been any other nationality than Indian, it is unlikely that he or his family would have had to suffer as they have done. But then, as I told Fauzia, she should be grateful he was only awarded three years in the first place. India and Pakistan usually sentence each other’s cross-border spies to life, or worse.

As for Zeenat, my heart sinks to think of what she could have endured these past few months. If she has done something wrong, let a case be registered against her and the law take its course. If not, let her go. In either case, she and her family deserve better.