With the leash of the magical, Intizar Husain carried us into another world that was deeper, unfamiliar and unexplainable

The traditional fiction in this part of the world was dastaan and katha, both fantastical in their formal structure. While the beginnings of novel in Urdu was grounded in realism as it came down from the European tradition.

Cervantes’s Don Quixote, primarily allegorical in nature, was a take on the medieval fiction. Sarshar’s Fasanan-e-Azad, an Urdu burlesque narrative, was inspired by Don Quixote to following the picaresque tradition. Deputy Nazeer Ahmed‘s fiction, too, was based on the early European novels which was a continuation of the medieval romance, the moral tag being its integral part.

The fight between good and evil was the Christian moral vindication of the triumph of good over evil in medieval romance and Nazeer Ahmed, too, ended up painting the moralistic vision with local pigment, thus salvaging his work as being for the betterment of mankind.

Prem Chand, the super realist and master craftsman was more into the choices made in a society that was changing fast. His landscape was realistic and so were his characters and it often ended in the failure to make rational choices when stacked against the odds of traditions, customs, and system of beliefs.

The next generation of fiction writers aspired to a more layered and nuanced understanding of the human condition, thus rebelling against what they thought was a one dimension depiction of reality. Qurratulain Hyder’s Aag Ka Darya was obsessed with discovering the complexion of the subcontinent’s civilisation, the way it sprouted and then blossomed in thousands of years.

She did not begin with the arrival of the Muslims a thousand years ago but went beyond to dig deep enough to expose the roots that were very long, sinuous, entwined and parsed in the soil. There was so much else that it was not possible to unravel any further. It was as if the focus had moved gradually from discovering the nature of this complex mix to one that was continuously in the process of unfolding, of remaking, forming and reforming.

She went back and created characters of the same names in the epochs that existed in history, of eras long gone by to the times that she lived in. The eras, too, were in a way recreated by her to give a more wholesome feel to the complexity of their formation. The traces of the formative elements could be found in substantial quantity. Abdullah Hussein also went back in time but to a past being formed by the impact of European colonisation. The character types and social transformation created as a consequence then cast their long shadow in the contemporary era. It was a more sociological than incisive journey through the layers of evolving consciousness.

Intizar Husain charted a course different from the others, though it can be said that there were similarities. He was acutely aware of the significance of the past and its defining role in the formation of sensibilities. As he looked inwards at characters living in present times, pointing his analysing finger at both the fund of the consciousness of what had made them into what they were, it also earmarked the resources of coping with the challenges or the ways of the present. He found a constant tussle in the characters, neither a complete retreat of delving into the past nor a heroic confrontation with the present.

But then he was not alone as a whole movement was in the process of looking into the complexion of the human psyche and what really informed it. There was much that was being experimented and analysed in the name of psychology. Freud and others were unfolding the mysteries of the consciousness and the overriding relationship with the unconscious, and Carl Jung placed all this within the ambit of civilisation.

So, Intizar Husain went back initially a few decades to the years of his own growing up but, not fully satiated, went much further back into the realm of mythology and the experience that appeared to human consciousness as fantasy. This was literature that preceded the age of realism -- the latter, an import of the West that placed the character and action against the acid test of Aristotelian canons of credibility and unities, but the former, fiction in non-European ethos not bound by any such obligations of realism.

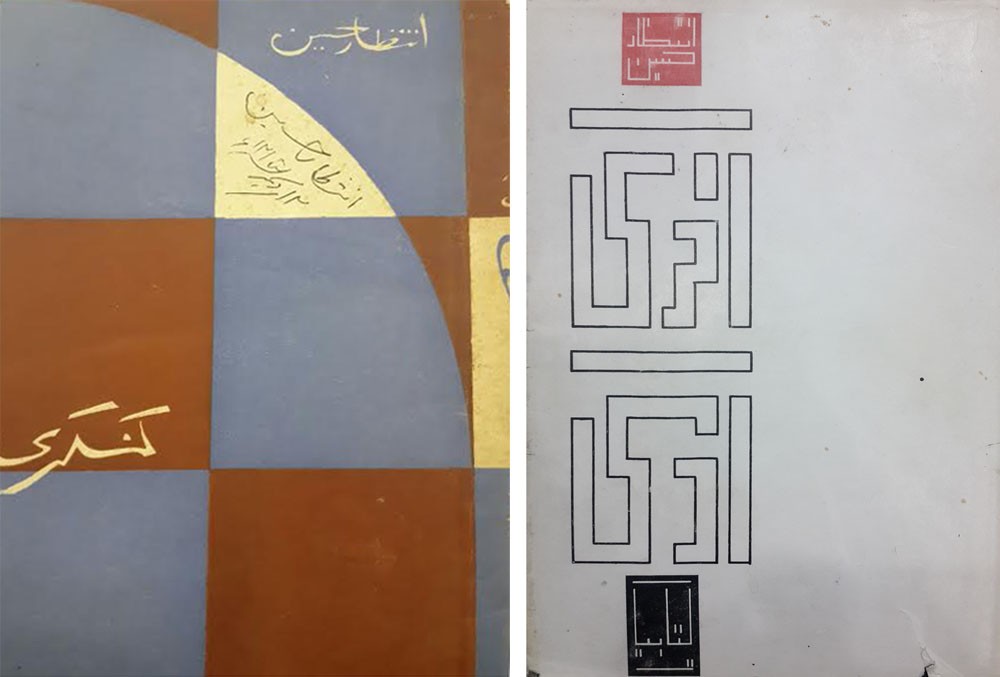

Read also: Quddus Mirza on Intizar Husain’s art of writing

In the world of mythology, phantasmagoria and the unexplainable the biggest challenge was to make it conform to human understanding. This delving deep into human consciousness and wanting to understand was done by Qurratulain Hyder and to a greater extent by Intizar Husain. It was in a way a continuation of the tradition of the dastaan which basically, through the fantastical overrode the moral circumference and created a landscape that was whimsical, unquantifiable and, hence, beyond the pale of establishing a value of good and evil. It was an exploration into the recesses of the human consciousness. It was more a psychic journey than an address to reach.

It may be said in the same breath that though the symbols and metaphors which are archetypal have a certain universality about them for they occur and recur in all literatures and other artistic expressions, the artistes and the writers are required to give them a local habitation and a name. The fiction of Intizar Husain was, thus, totally steeped in the contemporary locale, when he wanted it to be so.

And the ready reference to things that were there, experienced, seen, heard and observed lead into another realm which was not that obvious in the beginning. With the leash of the magical, he carried us into another world that was deeper, unfamiliar and unexplainable, while the familiarity of the local and the external appearance did not go away either. It was the constant interplay of the two that gave vibrancy to his work. The very crucial connection gave his writings a living vitality.

As far as the society and the characters within that social order are concerned, the inner force and complexity of subjectivity failed to find an adequate place in its objective societal construct. Ashfaq Ahmed had tried to strike a balance but his fiction petered out as forced in the one dimensionality of the received truth in its objective form. There was this constant unease, the feeling of not being there, a lack of adjustment that informed Intizar Husain’s fiction.

The Basti inhabitants were constantly wanting to re-plan and re-design the settlement and their habitation, and it led them a little later to a realisation that this pushing and shoving was forever. As long as people inhabited the settlement it was in a state of maladjustment and only by being driven into the sea Aage Samandar Hai this maladjustment could come to an end. The last option of being driven towards annihilation for a resolution, thus ending the constant tension and tussle is what informed his ultimate but tragic vision.