Most advance-stage cancer patients are denied treatment. Palliative care and hospice can prolong their life, improve quality of life and help them die without pain

Muhammad Hanif, 65, was not aware that his hepatitis symptoms had worsened and ultimately transformed into a cancer of liver.

Acting upon an advice given by a friend, he had stopped visiting the specialist and opted for herbal and homoeopathic medicines. It was only after his condition deteriorated and he was taken to the hospital that the truth dawned on him. His tests were done and it was discovered that he had cancer which was at an advanced stage.

The news came as a rude shock to him and his family. What’s more, the hospital where Hanif had gone refused to admit him on grounds that his disease was not curable. Over the next few days, his relatives tried to influence the hospital administration to take him in; to no avail.

Hanif was prescribed some medicines by the oncologist in the outdoor patient department and asked to return after a month for a followup. This shattered him. He had lived his life with grace and never wanted to become a liability.

Hanif’s is just a case in point as a large number of patients at stages 3 and 4 of cancers are commonly returned by the hospitals. To quote Prof Dr Shehryar, a renowned oncologist and President, Cancer Research and Treatment Foundation, "Every year, around 185,000 new cases of cancer are added to the existing pool of patients. Of these, only 29,000 get treatment at different facilities including Mayo, Sir Ganga Ram, Jinnah, CMH, Inmol, and Shaukat Khanum Memorial Trust Hospital (SKMT) in Lahore; Allied Hospital, Faisalabad; and Nishter Hospital, Multan.

"Has anybody tried to find out what happens to the rest?" he asks. "These people are left on their own.

"Their disease, even if incurable, can be managed well," he declares. "In fact, it is as manageable as hypertension, diabetes and arthritis."

Explaining his point, Shehryar says that of all the diagnosed cases, almost 30 percent are at the curable stages 1 and 2 whereas the remaining 70 percent are at the advanced stages 3 and 4. The latter lot is denied admission at the hospitals and the main reason for this attitude is the shortage of cancer hospitals in the country.

He laments the fact that there was only one dedicated cancer hospital in a country of over 200 million till December 29, 2015 when the second branch of SKMCH was inaugurated in Peshawar. "The international practice is that there should be a cancer hospital for every 5 million people in a country. In New Delhi, there are more than 10 cancer hospitals."

So, the question arises as to what is the practice in countries with developed healthcare systems regarding advance-stage cancer patients? The answer is that they have palliative care and hospice treatments for such patients. These disciplines are about managing the disease effectively.

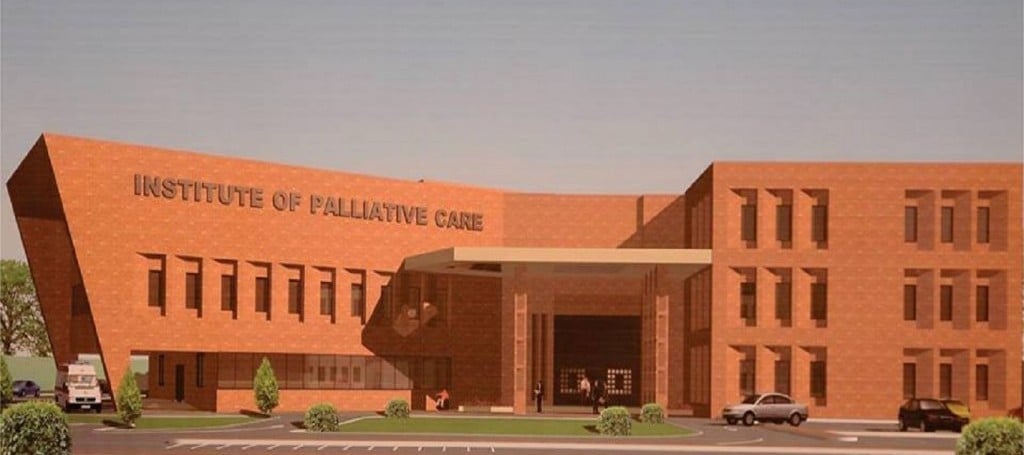

"We’ve never had a proper palliative care unit in Pakistan," he adds. "Thankfully, Lahore is going to have its first, fully functional, 100-bed institute of palliative care, probably by the end of this year, on Raiwind Road at a distance of 20 kilometres from Thokar Niaz Beg. No terminally ill patient shall be refused admission here. Besides, they shall be given free treatment. This will be the first such facility in Pakistan and the biggest in South Asia."

The said institute shall be run as part of the Trust’s 400-bed Cancer Care Hospital & Research Centre.

In this context, one is reminded of late Hassan Asif, a Pakistani student in Australia who received end-of-life care for skin cancer at a Melbourne hospice. Earlier, he was getting outreach palliative care at home but was moved to a specialist medical facility when his condition deteriorated. He was too sick to fly back to Pakistan. The Australian High Commission initially rejected his visa application but later on approved it on humanitarian grounds. He was very well aware of his condition and the fact that he was going to die soon.

"Hospice is also about managing death," says Dr Riazur Rehman, who is working as a senior consultant in the Department of Radio Oncology at Jinnah Hospital. He has also served in Malaysia where he was awarded at the state level for helping to establish a world-class palliative care unit and sent to Australia for specialised training in hospice treatment.

"It’s not like writing a prescription; it is like developing a whole system where you have a dedicated team of volunteers, nurses and doctors who are aware of the psychological and physical needs of the patients, their families who are trained enough to handle these end stage patients and support at private and state level."

Rehman says that a study conducted by his team found that 80 percent of cancer patients in Pakistan are at the last stage of the disease. Many are given the very expensive chemotherapy because of a lack of awareness and poor health facilities especially in rural areas where the majority population lives. "What these patients need is palliative care, especially in a country like Pakistan where there is no health insurance system.

"We need to set up hospice and palliative care units in all the tertiary hospitals in the government sector, as a first step, encouraging the society to come forward and provide care to these unfortunate people."

He says pain management is a major issue for cancer patients and can be done by using opiates like morphine and other drugs depending on the needs of the patients. Psychologists, religious personalities etc are also engaged in sessions with the patients.

"It is also true that the life of stages 3 and 4 cancer patients can be increased by 2-5 years and the quality of end stage cancer patients improved through palliative care and hospice treatment. But if they are turned away from hospitals, they die in days or weeks."

Rehman shall be heading the palliative care unit being set up on Raiwind Rd. The unit is being constructed on a 125,000 sq ft area at a cost of Rs43 crores. "The public response to appeals for donations has been great so far," he says.

The rooms at the unit are said to be equal to the standard of a 5-star hotel with facilities customised to suit the needs of the patients. They will be made in a way that sunlight can enter so that the patients who are bed-ridden do not lose the orientation of whether it is day or night at a particular moment of time.

He says there is a perception that in the presence of Shaukat Khanum Hospital there is no need for another hospital. "I would simply say that Imran Khan has set up an example to be followed and now the big corporates, philanthropists and the state must come forward and help to establish a network of cancer hospitals throughout the country.

"We have moved a request for a grant to the Punjab government and are hoping for a positive response. When we have it we will immediately buy machines and start free-of-cost breast cancer screening facility at doorstep."

Dr Riaz ur Rehman says they have trained one doctor and a nurse each from all 36 districts in palliative care and hospice and prepared a battalion of volunteers, many from colleges and universities, who will provide outreach care services to advance stage cancer patients in their homes.

Irfan, a student of accountancy and a volunteer under the project, says he decided to volunteer when he spotted a female cancer patient and asked her why she was crying. The lady who had a disfigured face said she was not crying for the fear of death. She was crying for the reason that nobody would like to see her face after she had died. "I realised the need for getting her regain her self-esteem before she died and decided to become a volunteer," he concludes.