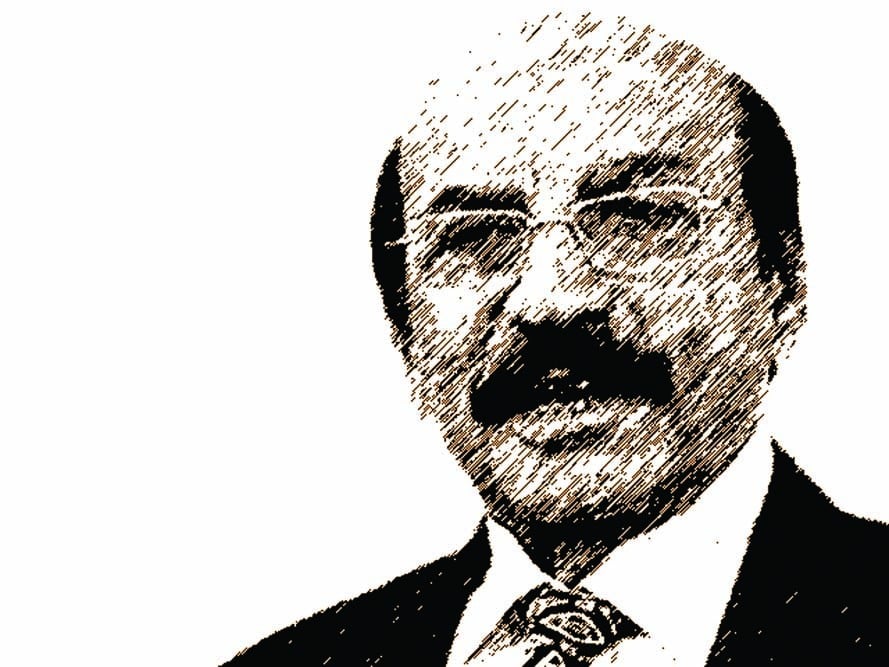

Braving the ceaseless cacophony of criticism for everything that is wrong in the province since 2008 is one man -- Syed Qaim Ali Shah, the octogenarian chief minister of Sindh

The Pakistan People’s Party’s (PPP) has been at the helm of Sindh government for eight years at a stretch now. Under its watch, the province has faced some of the worst bouts of lawlessness, allegation of corruption and natural disasters and the party’s attempts to rule the province can only be explained as a journey from one crisis to another.

From a steep rise in Karachi’s target-killings in 2009 to the many shortcomings in the rehabilitation of flood victims; from the dismal state of government-run schools in the province to the performance of law enforcement agencies under its command (not to mention the allegations of corruption at every level), the PPP’s governance of Sindh has been projected an endless nightmare in the media and the perception continues.

Besieged by countless horror stories of failures from Karachi to Kashmore and braving the ceaseless cacophony of criticism since 2008 is Syed Qaim Ali Shah: the octogenarian chief minister of Sindh, the man in charge.

Shah’s political career differs from the many bigwigs of traditional rural Sindh, where the socio-political leadership is taken as birthright that comes with one’s surname. He was born in a middle class family and trained as a lawyer. Unlike the Jatois, Makhdooms or the Bijaranis who have historically ruled the tribally-fractured province, Qaim Ali Shah does not belong to Sindh’s influential landed gentry. He made his place in the party over decades, proving his loyalty in a career now spanning almost 50 years.

It is interesting to note that the squiggly bureaucracy put in place to run the province is replete with corrupt officials at every level, but the chief minister, in his long political career, has remained relatively safe from allegations of corruption. Observers say it is no small achievement. "In Sindh, where a majority of powerful government officials are often accused of financial malpractices, the man at the top was never directly accused of any wrongdoing," says senior political journalist Mazhar Abbas, who has been a reporter in the province for over three decades. "It tells you a lot about his character."

However, many question the claim that the chief minister is actually at the top of Sindh government. But when it comes to the Sindh government’s many failings, he is the man to be blamed.

"He is one of the most soft-spoken persons in the cabinet and has proved his loyalty to the party time and again, including during Zia-ul-Haq’s days, when several top leaders either left the PPP or went AWOL [absent without official leave]," says Sohail Sangi, a veteran political activist from Sindh. "But Shah stood his ground and was the provincial president of Sindh during the toughest of times."

Shah entered politics in the late 1960s when he was elected as Khairpur’s district council chairman in Ayub Khan’s era. He was soon spotted by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and was one of the members of team that founded the PPP.

In the 1970 elections, Shah was elected member of the National Assembly from his hometown Khairpur and become Federal Minister for Industries and Kashmir Affairs. Since then he has won the National Assembly seat from the constituency seven times and for the first time became the chief minister of Sindh in 1988 for two years.

Experts say that apart from his seniority, which played a role in his appointment as chief minister for the second time in 2008, it was his polite demeanour that was certainly taken into account. When the PPP and Muttahida Qaumi Movement entered a coalition to set up the provincial government, a non-provocative person was needed to fill in the shoes. "Unlike many PPP leaders who often fall back on identity politics, raising the ethnic polarisation of Sindh to appease voters, Syed Qaim Ali Shah never resorts to such rhetorical politics and was acceptable to everybody," says Abbas.

But when it comes to delivering results, Shah has fallen way short of expectation. As Jibran Nasir, a youth activist whose video clip, confronting the CM outside a public hospital in Karachi last June, went viral, says, "Compared to the rest of the country, where you have a semblance of governance, the Sindh government pathetically lags behind. Go to any provincial department it is the same story."

The people of Sindh, says Nasir, have taken many of the public issues in their own hands. He cited the recent online campaign initiated by Pakistan Tehreek Insaf’s youth leader, Alamgir Khan Mesud, who is drawing the CM’s mugshot outside lidless manholes in Karachi with a tagline "fix it". "If a young man can fix all the open manholes with Rs 13,000 on one of the main roads of the city, why can’t the government with its billions of budget and a huge machinery do it across the province?" he asks.

Nasir notes when it comes to issues that do not directly concern the masses like the arrest of Dr Asim Hussian, a close aide of PPP co-chairman Asif Zardari, the whole Sindh cabinet jumps into action, protesting, passing resolutions. "We never see such flurry of political activity when the people of the province suffer," he says.

But in a party that is run with a clannish mindset by the immediate family of the chairman, how much power does the chief minister actually wield? Is it justified to blame Shah for everything that is wrong with Sindh today? From a constitutional perspective maybe yes, but in practical terms it is difficult to tell.

Historically, the Bhutto family [including the son-in-law Asif Ali Zardari and his family] are revered as the heirs of a legacy. So the leaders, no matter how senior, never really have much of a say in the running of its affairs. Many of the decisions that are owned up by the chief minister basically come from the high-command or people close to them, say observers.

"It has always been this way; senior leaders are given a certain amount of freedom but the last word usually from the top," says Sangi. "The attitude is more like as long as a Bhutto wants me to be the CM, I will remain the CM. It’s a favour."

In other words, the chief minister is the poster boy for the PPP’s many failures. And unlike other PPP leaders who can be relatively assertive, Shah’s polite attitude only makes the matters worse. As a senior leader, trained in the PPP’s tradition, Qaim Ali Shah almost has a rapacious ability to take criticism, which is a sure sign of a mature politician. But the quality is often read as insensitivity by many.

Abbas argues that Shah is a shrewd politician, and many of his overt gaffes in the media should not be interpreted as mere slipups but are positions taken after deliberations.

"It’s the bureaucratic juggernaut that often fails him or restricts his administrative capabilities, but certainly we cannot skip the fact that as the CM, he is ultimately responsible for anything that happens under his watch."