Retrieving Jinnah from the shackles of the religious right

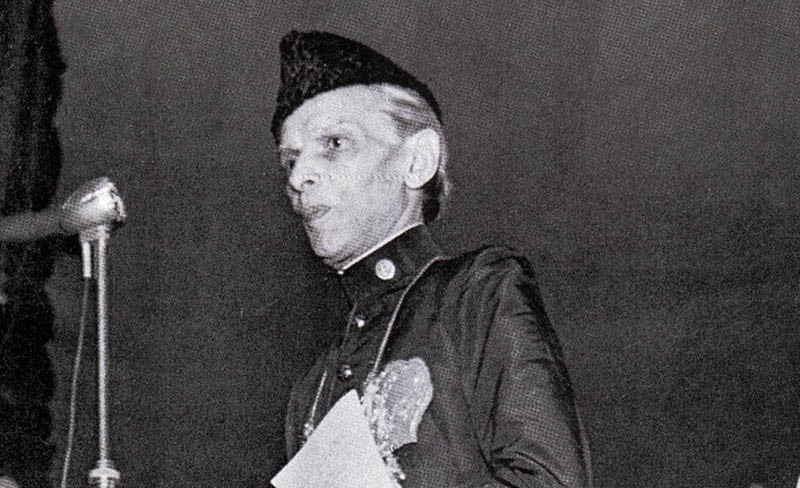

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s 139th birth anniversary offers us yet another opportunity to reflect on how he has been iconographed in Pakistan during the 68 years of its history. Iconography is a branch of art history, which studies the identification and interpretation of the content of images. The nationally-constructed image of Quaid-i-Azam, which is in wide circulation in the entire country shows him wearing a karakali cap, sherwani and chooridar pyjama, as if he represented the culture of UP Ashra’af.

He was a leader of the All India Muslim League (AIML) which had its resurgence in the 1940s primarily because he lured the Muslims of all hues to join that party. Thus AIML had among its ranks, the liberals, socialists, landlords, business magnates and some clerics. Quaid-i-Azam had to recruit some of the clerics so that the Deobandi diatribe against Pakistan could be blunted.

Ironically, right after the demise of Quaid-i-Azam, the least important and the most peripheral segment of those campaigning for Pakistan became the most important. Even within Muslim League, the socio-religious plurality that the Quaid vehemently emphasised eventually evaporated like a mist in the morning. Such unilateralism which found currency during the early phase of Pakistan’s history, subsequently, transformed the very perception of Quaid among the general public, too. He was re-invented thoroughly and while doing so his (modern/Western) past was completely obliterated.

In view of what has been said above, it will also be interesting to deliberate on the way the founder of Pakistan was variously represented by different interest groups, particularly the liberal-right and the religious-right. Here it will not be out of place to distinguish one from the other. The liberal right lends support to any cause considered to be for the betterment of the Muslims. In practice, however, the subscribers of such stream of thinking are modern. Another feature of them is their uncompromisingly anti-Indian stance.

Having said all that, it has to kept in mind that the cadres of the liberal right underwent a process of erosion. Many of them have switched over to the religious right. Religious right on the other hand, despite being a beneficiary of the fruits of modernism, keeps pressing for the promulgation of Shariah. For the last few decades, it has resorted to takfeeri and exclusionary tactics, invariably invoking a literalist interpretation of the foundational text(s). Its unflinching support for violence has made it into an existential threat for the state of Pakistan.

The iconographic image of Quaid-i-Azam which is ubiquitous in Pakistan provides representation of a typical Muslim leader aspiring to carve out a space for South Asian Muslims where he wanted to promulgate the edicts corresponding to Sharia. Quiad-i-Azam’s characterisation of a devout Muslim wanting to relocate the state of Medina in the North West of the subcontinent was unequivocally professed and fostered during the reign of Ziaul Haq (1977-1988). Then it became a core part of a Pakistani official narrative.

The Zia era provided a watershed moment because the representation of Quaid was re-done in the light of Islamism with fundamentalist (literalist) orientation. All of a sudden, Quaid was transformed from a liberal, Western educated Muslim leader who started his political career with Indian National Congress to a Muslim zealot, aspiring for Islamic renaissance.

Previously his iconographic image was monopolised by the liberal right and the daily Nawa-i-Waqt being its mouthpiece with several intellectual strands toeing the line of thinking that it championed. Its editor(s) like Majeed Nizami and before him his brother Hameed Nizami were the biggest stalwarts of that intellectual tendency, which was predicated on anti-Indianism. Meem Sheen, Z.A. Sulehri, Altaf Hassan Qureishi and Munnawar Mirza were some of the examples who spent their entire lives, propagating antipathy for India, which to their estimation subscribed solely to the Hindu ideology. They hardly had any consideration for the plural, secular ethos that India under Jawahar Lal Nehru was trying to project as the basis of their nationalism. For them Savarkar, the architect of Hindutva, and Gandhi, the one who lost his life because he was perceived as pro-Muslim, were two sides of the same coin.

Interestingly, that veteran breed of journalists cum scholars has proliferated an equally zealous generation of scholars. They are not only anti-India to the hilt but anti-pathetic towards America and the West in general.

The people whom I am branding as the liberal right made a common cause with the religious right (Ulema and religious parties etc.) in condemning the left. Surprisingly, the sectarian fissures did not become prominent enough to cause any concern. The fear of Russian bugbear left very little choice for them to assert their autonomous positions. Thus, they kept their ranks tightly closed. That mutuality between the liberal right and the religious right lasted until the Soviet Union rescinded its state ideology.

Once the leftist scare had become a saga of the past, religious literalism with the support from Saudi Arabia landed Pakistan into dire straits. Shia-Sunni schism eventually ripped the social fabric apart. Religious parties started espousing the cause of the militants. In such a situation, Quaid, his struggle and message became absolutely null and void. As Pakistani populace is coming under the influence of literalist (Madrassa-educated) Ulema, our founding father will fast become irrelevant.

Sunnification of the state or Saudiisation of the state is what, one reckons with certainty, Quaid-i-Azam never aspired for. Sadly, things don’t look promising. Such a situation will not end unless Quaid would be retrieved from the shackles of those representing the religious right.