In his recent collection of prose writings, Zafar Iqbal writes about his own experiences as a poet and not as a professional critic

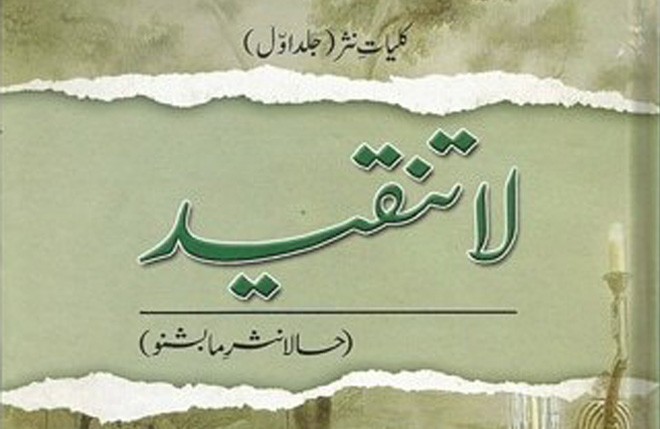

Zafar Iqbal’s collection of prose writings published under the title of Latanqeed further consolidates the point of view that he has always held -- that ghazal as a form of poetry has immense possibility of growth. It should be looked into creatively rather than being dumped in favour of other forms of poetry like nazm.

Zafar Iqbal is primarily a poet and a ghazal poet or a poet of the new ghazal and that criticism or prose writing is in relation to his poetry. This was at least the role of the poet/critic before a whole army of literary critics joined in the war effort of shelling canon balls on to the other side of the divide. Whatever Iqbal wrote was in relation to his own endeavour as a poet and not as a professional critic. His role as a columnist should be viewed in the same context because his columns too veer towards literary rather than focus on the political issues that have bedevilled the reading public.

What has been preferred now for more than a hundred and fifty years has been the nazm. During the 19th century, there was an effort from the top to write poetry in a new form as it was alleged that the major form, ghazal, had become dated. The ghazal had exhausted all possibilities and that the changing times demanded a new form. Efforts were made with this poetic initiation to write on themes that gradually gave way to another form, nazm which was a new form for the people and culture here but had a very prestigious place within the hierocracy of poetic forms in the West.

Since then nazm has been viewed as the major vehicle of change and expression of poetry in Urdu language.

For Zafar Iqbal, nazm was a foreign form; it was imported and the local poets started to stuff their sensibility into the mould of this new form. The preferred option should have been the exploration of the existing indigenous forms, like the ghazal, for a change of expression as a result of the change in sensibility. There was great possibility of the inner growth of the ghazal form. It was not fully looked into and was left aside resulting in the nazm exhausting itself too soon since it was not compatible with our local sensibility.

He builds his arguments on two counts -- one that the human experiences do not really change or that the quantum of change is not that much. He cites the stock experiences or themes in Urdu poetry to bolster his line of argument. The nature of the experience remains the same; what actually changes is the language, the expression, the idiom. It is language, according to him, that is the repository of contemporaneity.

What distinguishes the older poetry from the current one is actually the changed language and changed expression. There he stresses that what is required is to make the language or the diction of the ghazal as being from current times and the rush towards new and fresher experience is premature. He himself, in his poetry, made daring experiments with language while remaining within the formal structure of ghaza. He calls that range of experimentation as legitimate but the rest as venturing into someone else’s cultural and artistic domain.

Zafar Iqbal appreciates that because he was impressed by Russian formalists who focused on language and called it the only area worth studying. Similarly, he too has focused on language thinking the form and genre can take care of itself being of secondary nature. It is when the secondary become primary then he starts to have issues with it.

The old debates about Urdu, the Delhi-Lucknow divide, and the imitative role of Punjab have become history and fizzled away with Urdu being relegated in the places of its origins. Urdu for him has greater chances of growth if it draws from the fund of the local languages in Pakistan like Sindhi, Punjabi, Pushto and Balochi, not to mention many more dialects. He has incorporated words and phrases from local languages to enhance and widen the diction of ghazal.

But what is left undefined and not properly spelled out is the relationship of language and expression to change and then the relationship of that change with the formal structure in literature like that of ghazal and nazm.

It must be said that, where prose is concerned, Zafar Iqbal has a certain facility with language and he makes his point forcefully and without burdening it with the gobbledygook or technical verbosity. Actually, he has issues with the process or criticism that is over-laden with technical details and an expression that is not lucid and he should not be blamed for it.

In the near past, schools of criticism growing out of structuralism, post structuralism and deconstruction have added greater obfuscation to the schools that advocated new criticism and socialist realism. There is much in criticism that has to be liberated from the clutches of verbosity and profession jargon. Criticism too should be kind to the reader rather than make a case for its own erudition.