Some years ago I wrote a piece on the dismal state of our libraries. This was after I read that in a seminar on business management, in Karachi, the chairperson had suggested that what our libraries needed were not books but computers and CD-ROMs. He must have been influenced by Tony Blair’s mania for computers in schools. Mr Blair, better known as Bush’s poodle, was one of the worst prime ministers Britain ever had.

The influence of Blairist technophiles affected television in England in a big way. It prompted one ITV (Independent television) programming department to try to create the perfect programme entirely by computer. All the elements of current shows were fed into a piece of software, including locations, stars, characters and, of course, ratings. What emerged was horrible. It turned out to be a half-hour ensemble sit-com about bin men set in Manchester. It contained every cliché in the book.

The best dramatic presentations on television came out of BBC I and BBC 2 in the last forty years of the twentieth century. Classical, restoration, modern, contemporary, you name it, the Beeb presented one gem after another. These programmes were not recommended by market researchers after gathering data from polls, but because the enlightened producers of drama felt that the works they screened were part of an enormous literary heritage that ought to be aired.

But as things became more competitive and ‘ratings’ became the all important factor in programme-making, a new phenomenon called concept-testing came into existence.

Concept-testing (it would be hard to find a phrase less pleasing to the ears) was the brainchild of a researcher, David Brennan, who was working on the Broadcaster franchise bid on behalf of Tyne Tees TV network. He needed to know if any of the new programmes it was proposing to the Independent Television Commission would work. Brennan decided to ask members of the public if they would actually watch what was proposed.

The Independent Television Commission was formed in England to regulate the existing independent ITV networks (the independent in this context indicated freedom from the BBC rather than the government because that freedom is taken for granted). It was the Independent Television Commission that allotted franchises to the fifteen television networks that functioned in the UK.

Tyne Tees was one of the smaller networks covering a small area. Brennan’s system worked. Tyne Tees got the franchise and Brennan, having scored a huge success, moved, within a year or two, to run the whole of ITV’s programme research centre. By 1993, ITV had become more sophisticated in its use of research. Rather than put a new programme idea to a member of the public, ITV created a false listings magazine with its proposed new programmes interspersed with totally false fictitious ideas.

Brennan had now resorted to a new technique. He realised that if you presented a whole new programme idea to someone in outline for the way a commissioning editor would, it would be too conceptual. Instead, you gave them the same information a viewer gets when a programme is launched -- listings information and a trailer. Then you can ask why they chose it and what they liked about it without forcing them to focus on it.

The BBC, which had been willing to risk failure in pursuit of creativity, also relented and began concept-testing in the 1990s, but used it much less than ITV where every second of airtime had a commercial imperative to make money and bring in the right audience for the advertiser. With costs for location dramas hitting to well over £500,000 an hour, (today it is nearly twice as much), it was hardly surprising that broadcasters began to test ideas before they invested such huge amounts. BBC’s costs were slightly lower because they kept producing quality drama and could lure all the top actors eager to play the meaty parts offered to them, at a lesser price.

Critics of concept-testing kept saying that it led to bland programmes. When it is used on its own, it would not dictate whether something was made or not. The device was just one element of the whole debate about whether programmes should be commissioned on the basis of sampling public opinion or not. Some programmes that were made, as a result of concept-sampling, turned out to be huge flops. If research could really tell you exactly whether everything would work, you would need lots of well-paid programme executives. Interestingly enough, it was these highly paid executives who were the ones in charge of concept-testing.

Vast sums of money were invested in tv programmes because if and when a programme got top ratings, advertisers were willing to pay more for their ads. A thirty second advertisement during peak viewing hours cost the advertisers £250,000. This was the rate in mid-nineties. It would certainly be considerably more today.

*****

In our country we are now thoroughly addicted to television. The subject of books is discussed only in English newspapers. We have television galore and we don’t need any development analysts to advise our tv bosses what kind of programmes they should offer to the viewing public. When it comes to entertainment, our TV executives simply look at what is shown on hundreds of Indian Channels. They then instruct their programme-makers to imitate a similar soap opera (with every female, maiden or spinster, layered with make-up even when asleep) and a similar musical programme interspersed with crude comedy. The rest of the time is filled with verbal jousts by political analysts.

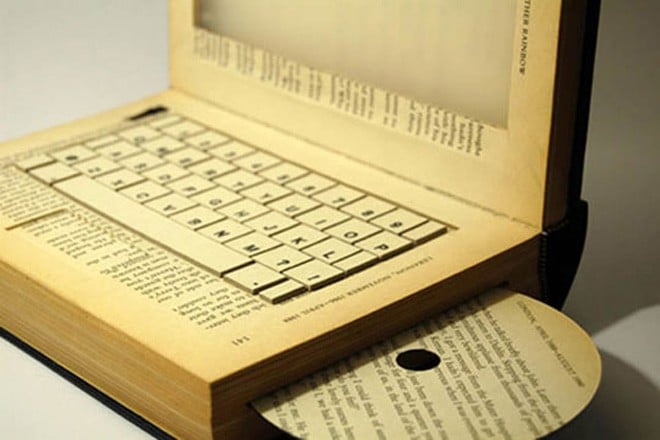

The business magnate who wanted to stock up our libraries with computers had obviously not been near a book. I do not mean a reference book, but a real book which gives refined delights of character and cadence, irony and allusion. A book affirms that we are part of something bigger than ourselves. In reading a book we are humbling ourselves before the author’s intention, absorbing ourselves in the possibility of seeing things differently.

*****

By the time we got into the 21st century it had been assumed that computers and thousands of tv channels that operated throughout the world had put books out of business. In America, there was widespread conviction that all books are dying a slow death. The New York Times (the Pope of all newspapers) had carried stories suggesting that the whole American publishing industry was going out of business.

A book is not just an information storage medium like tape or a floppy disc. It is not just something we use. We are one with a book. A computer these days is just one year old, and your daughter’s laptop will be archaeology by the time she leaves school.