In a recent exhibition at Rohtas 2, Lahore, Khadim Ali and Sher Ali focus on mythologies of the oppressed

In one of his essays, Intizar Husain points at the distinction between literature (or art) and ideology. He says that diverse and contradictory practices of creative expression can coexist in a society whereas one ideology seeks to negate, dominate or diminish another one.

We have witnessed this conflict of ideologies or clash of civilisations in our part of the world. For several years, Pakistan was an active participant in the affairs of Afghanistan’s civil war, fought in the name of democracy, freedom, faith. In the words of Slavoj Zizek "Forty years ago, Afghanistan was an open, technocratic, secular country. It is through its very involvement in international politics that it became fundamentalist…" It came to be ruled by militants of medieval mentality, and still is in danger of reverting to a Taliban regime.

Like a good neighbour, Pakistan has welcomed refugees from this war-torn country for many years. Along with immigrants, we have been blessed by two artists from that Republic. They both moved here due to different circumstances - one owing to persecution of the Hazara community during the Taliban rule and the other is a foreign student at the Beaconhouse National University (BNU).

Both have enriched the cultural and artistic fabric of this country. Khadim Ali’s family travelled to Quetta when it was difficult to survive in the ‘Sunni’ society of Afghanistan. Born in Balochistan, he was enrolled at the National College of Arts as a local student. It was only during a discussion about his works and certain references in his art that his contemporaries became aware of his link with Afghanistan. Sher Ali joined BNU as a SAARC student representing the present state of Afghanistan.

Knowing their background, one is familiar with the difference in their approaches. Khadim Ali studied miniature painting and has developed an individual vocabulary, drawing influences from the literary and pictorial tradition of Rustom and Sohrab battle illustrated in various illuminated manuscripts. Sher Ali, much younger than Khadim, produced works in multiple formats during his graduation at BNU, which were exercises and attempts to explore new mediums, materials and methods without a connection or burden of history or geography.

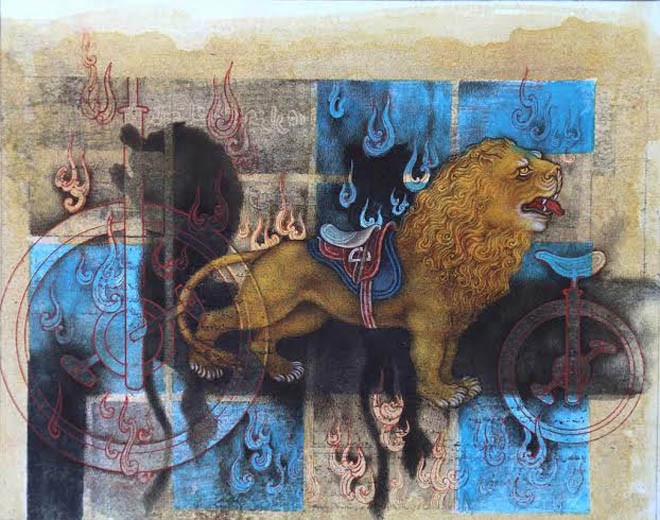

However, in a recently-held exhibition Mythologies of the Oppressed at Rohtas 2, Lahore (Dec 19, 2015-Jan 2, 2016) one comes across a different Sher Ali. Here both him and Khadim Ali are showing works created in mixed media and gouache on paper. The size as well as the style of rendering and the choice of imagery do not distinguish one Ali from the other; to the extent that one starts to speculate on the characteristics of ‘national art of Afghanistan’. In his four works on paper, Sher Ali has portrayed lions trapped or tamed in circus and draws them in different acts such as jumping through the circular rods of fire etc.

On a simplistic level, one can make a guess about Sher Ali’s preference to paint lions (because the word Sher means lion in Urdu and Farsi). On another level, the artist’s choice to focus on a beast that symbolises the state, any state for that matter, shows his concerns. As a lion is supposed to be the lord of the animal world, it is associated with several kingdoms and countries. For example, it appears in the emblem of the British Empire, on the flag of Sri Lanka and is the electoral sign of ruling party in Pakistan. At the same time, an animal identified with royalty, power, elegance and independence is often seen performing strange tasks at circus shows. Tricks like passing between burning wheels, standing with four legs balanced on a narrow stool and carrying the riders on its back reduce the status of the dominating beast.

Sher Ali has used this aspect of converting the metaphor of bravery into a meek entertainer not without a political context. Lions posing as if humans in a group around flames, the same ferocious creature with a rider mount on its spine next to singular-wheel cycles, or lying on ground while two men perched on one-wheeled cycles move on its body imply how nature is conquered but as farce.

One is reminded of a miniature from Company School in which colonial rulers are hunting tigers in India -- a work of art that can be viewed as the documentation of an ordinary occurrence or read as a symbolic depiction of British triumph over native forces, usually represented by Bengal tiger. In a similar way, Sher Ali chooses the lion to refer his homeland ("The lion nation, Afghanistan has been a site of near constant colonial struggle in recent history…." from both artists’ statement) and how the country has been subjugated to various forms of tyrannies and transformations.

Even though Sher Ali was not trained in the discipline of miniature painting, his works follow the aesthetics of the genre (border, scale, rendering etc.) and complement the art of Khadim Ali, the other participant of the exhibition. Khadim Ai has been employing the figure of demon, derived from the Shahnama, in order to denote the multiple types of discriminations. Like Sher, Khadim Ali is a Hazara and has thus experienced hatred and cruelties and feared the threat of extinction and genocide while living in Quetta. So the image of demons fighting among themselves or with others becomes a vehicle to narrate the fate of his people who, due to their facial features, are identified and marked as targets for their religious beliefs.

Khadim Ali investigates this dimension in which "minorities have become increasingly demonised by the establishment" (from the artists’ statement), by painting demons in settings which recall the conventional compositions of miniature paintings. His inclusion of golden clouds, halos and Persian script is an attempt to link the present with the past in which multiple histories exist side by side. Like the silhouette of Bamiyan Buddha being the ghost image behind the intricately-rendered blend of a man and goat in his paintings. The demolished sculpture now survives as a hallucinatory memory in our minds but for Khadim Ali and his community, the tyrants who bombarded Buddha are the same who persecuted and executed an innocent community for being a different sect (Perhaps, due to this connection, the artist has made an outline of canon in the background of his characters).

Khadim Ali’s decision to illustrate the plight of his people is commendable but, for a number of years, his imagery has remained the same. His skill, ideas and concerns are remarkable but similar visuals and vocabulary make one wonder if oppressed in the title of exhibition also refers to painters enslaved by a certain style.