In his recent show at the Lahore Art Gallery, Mohammad Ali Talpur, the viewer loses all sense of time and space trapped in the unfolding of visual formats

First he strips the language of its meaning and then removes the sound from it. The art of Mohammad Ali Talpur is about exploring and excavating the secret of script. Currently on display (from Nov 25-Dec 26, 2015) at the Lahore Art Gallery, his new works reveal the artist’s concerns and confirm his command on pictorial vocabulary.

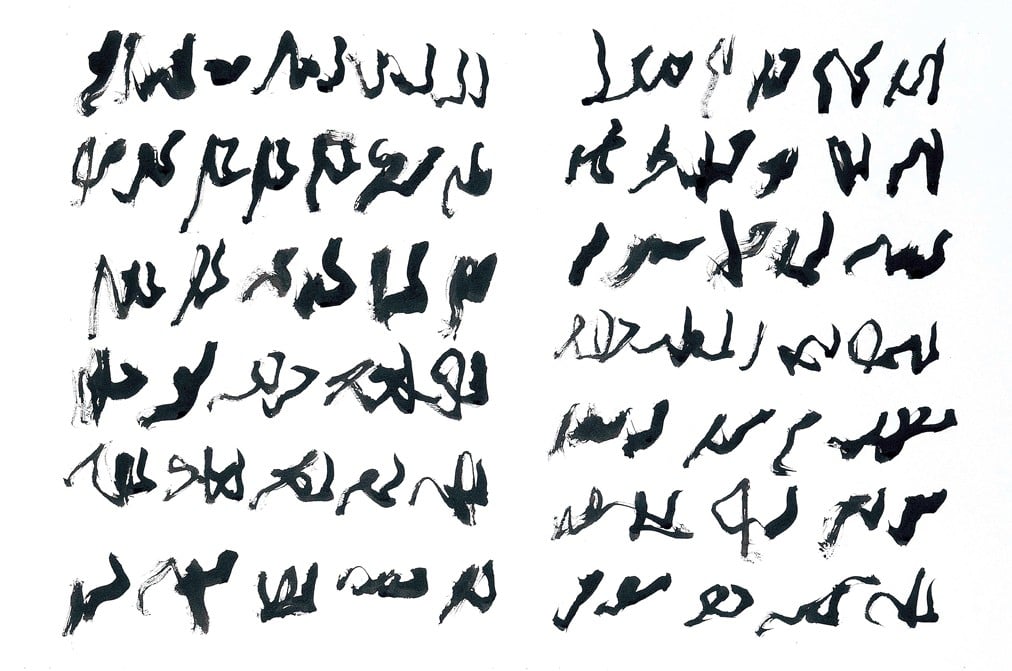

On a first glance, the works can be segregated into two groups -- on the basis of scale as well as the method of image-making. Large paintings on canvas are constructed in a specific scheme -- almost in a mechanical manner with sharp lines, clear edges and meticulous layout. The other part of his solo show includes works on paper with calligraphic marks, loosely rendered with ink and brush. In these works, one finds lines arranged as if on a singular page, two leaves of a book, or in paragraph-like compositions.

The two bodies of works are apparently separate, since one category signifies a certain methodology of making, time spent in execution, and precision; while the other suggests a sense of spontaneity, quick scrawl and randomness. Yet, the two are connected because both relate to one entity - language, rather to its manifestation in written form. All of his work is about alphabets, either as singular but repeated units or together like in a manuscript.

On a basic level, the two kinds of handling can be compared to two ways of writing - one, typing on a computer in which no matter what you write or how emotionally you express, it is printed in a perfect format which often denies the involvement of a human hand; two, the custom of transcribing a text in longhand, in which along with the content of the text, the act of writing it is also a part of the message (in some cases the most important message). The two visual formats indicate the way an artist seeks and blends the source of language and the act of art-making.

In our surroundings, when an individual is enjoying the art of writing, we normally describe his creations as calligraphy. Essayist, literary critic and sinologist Simon Leys in his essay on Chinese calligraphy ‘One More Art’ observes "By its very etymology, ‘calligraphy’ means ‘beautiful writing’… What the Chinese called shu, however, simply means ‘handwriting’; the word is often paired with hua, ‘painting’ and, in this context, to speak of ‘beautiful writing’ would be as preposterous as to speak of ‘beautiful painting’."

If we bring the matter to our context, in Urdu, the substitute of calligraphy is khushkhati, which does not imply beautiful writing (as generally and wrongly understood) but lettering that pleases and makes one happy (like the term kush-shakal actually means pleasant face). The choice of word confers how the act of writing in an artistic or prefect scheme is not about conveying beauty but carrying an element of happiness or feeling of sublimity. It demonstrates that the visual outcome is not crucial but the experience of making and the chance of encountering it is more important. The state in which one writes words (often sacred text) is self-satisfactory, instead of a desire to get appraisal from outside.

This aspect of making, which can be defined as meditation, in a way is the key to unfold the art of Talpur. However, meditation must not be confined or limited to religious or spiritual experience because one can get the sensation through other means. Being in front of Mohammad Ali Talpur’s large canvases, one loses all sense of time and space (an essential characteristic of meditation) as the imagery reverberates in a way that a viewer is trapped in the unfolding of visual formats. A viewer standing in front of a large canvas of Talpur witnesses the magic of art because the physical object in front of him, a six by eight feet canvas, suddenly starts to expand, to alter its rectangular dimension, to change its flatness of surface and to guide the gaze of a viewer lost in the maze of marks, lines and shapes.

With Talpur, meditation is not a metaphysical indulgence but a physical act made possible by the architecture of his imagery. Variations on a single letter of alphabet, Aleph, the works are conceived and constructed as complex structures that engage a viewer with their interplay of spatial tensions, and make him oblivious of his physical, cultural and social surroundings.

One remembers the first letter of Arabic as described by Jorge Luis Borges in his short story The Aleph "He indicated that an Aleph is one of the points in space containing all points." In Talpur’s works, one is aware of the artist’s emphasis on the purity of verbal or visual experience since the two are in reality the same. One looks at the web of shapes which are initially derived from the letters of Urdu or Arabic alphabets, but their composition is like a piece of literature in which a reader loses the sense of his environment because these transpose a spectators to other impossible realms.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Talpur’s work is that despite its particular link with the practice, tradition and history of writing, it liberates one from superficial cultural connections as it relies on pure pictorial phenomenon. A person in the presence of Talpur’s paintings may have the illusion of dislocation, something that is evident in his other more ‘painterly’ works as well.

These works, although composed in shades of greys, stimulate a sense of chromatic world in which subtle shades are recorded. But, by and large, it is the flow of text that attracts and glues a viewer’s gaze to his surfaces. Seeing his works created with the twist of brush (a substitute of traditional reed pen), one feels the freedom, ease and elaboration of an artist’s touch. Because even though he is inspired from calligraphy, Talpur negates the notions of readability. In that sense, he asserts another aspect of our art. It is a way of rejecting the literalness besides extending the notion/function of art -- since it relates to sensory endeavours which have the power and possibility of affecting worlds beyond decipherable words.

Here one remembers Simon Leys, quoting an anecdote of a famous Chinese painter/calligrapher of ancient period. Some villagers went to him and informed about their suffering due to a man-eating tiger. To solve their problem, the painter wrote on a large banner: Tigers are not welcome here.

This belief in the power of image from archaic China can be witnessed in the work of Mohammad Ali Talpur which communicates that no meanings are welcome here, except the meaning of ‘visualness’ in art.