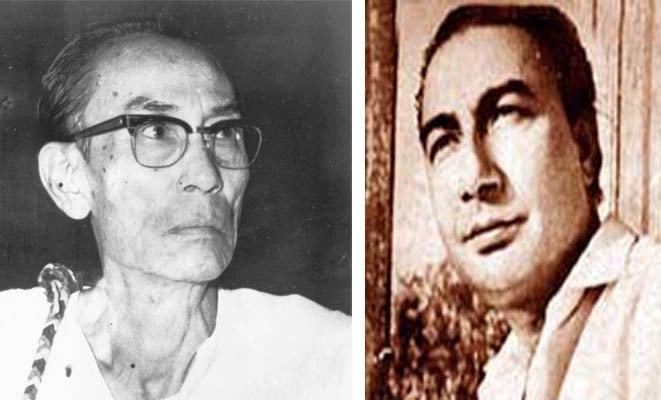

S.D. Burman, a great music composer for film in the subcontinent, and Sahir Ludhianvi, a poet par excellence, made a creative pair in Bollywood

Both Sachal Dev Burman and Sahir Ludhianvi, a successful and creative pair, died in the last week of October, albeit with a gap of five years. Both worked in fifteen films together and proved there could be a marriage of good poetry and composition which enhanced the overall impact of the final outcome.

Their falling out also took place because both wanted to be more important. Sahir thought that poetry took precedence over composition while for S.D. Burman it was poetry that was written to suit the musical requirement. Ironically, when Sahir was taken to Burman for the first time, the latter was not impressed by the poetry of Sahir for he did not really know Urdu or Hindustani to the extent of appreciating the subtleties of poetry. He was awed by Sahir’s ability to write verses instantly and with great deal of facility. As Burman composed, Sahir wrote what suited the musical composition, and the two ended up by working together and ratcheting up the general level of film music in the process.

Many think that S.D. Burman was the greatest music composer for film in the subcontinent. He was versatile and he also kept pace with the changing trends in music and composed accordingly, while hardly ever compromising on quality. Sahir Ludhianvi was generally perceived to be a very good poet who made his transition to film lyricism quite successfully. It was generally assumed, since the days of the theatre in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, that good poets did not lend their verses for compositions in the theatre.

Similarly, good poets did not offer their verses to be sung by the dancing and singing girls in the salons. The poetry or lyrics written for the salons or theatre were meant to be doggerel for those who wrote not what they thought should be written but what the situation demanded or required. Conceived as made to order and losing its primacy, poetry was thus placed on a secondary footing.

Almost all poets as indeed the man in the street hold on to this general assumption that music is nothing else but poetry composed or set to music. To a musician or a composer, on the other hand, words are only meant to be reference points that add a little concreteness to the absolute abstraction of the musical sound. To most composers, words are reductionism in nature compared to the overarching universality of the sur or the note. The absoluteness of the sound that defies connotation works over and above the limitation imposed by words.

In Europe the high classical music was instrumental while here the lyrics in the classical forms were written by the vocalists themselves (Tansen-Nemat Khan Sadarung-Bare Ghulam Ali) for they were meant to serve the musical idea. It was only in theatre or in dance that word and composition came together in probably equal measure to serve the ideal of theatre or dance performance.

Most of the poets stayed away from films but in India, at one point, it was thought legitimate that films should be made the conduit for spreading the idea of an egalitarian order. Lenin, too, favoured this mass medium as part of the outreach programme to access the masses. The films were joined by major writers/poets like Sahir, Majrooh, Jan Nisar Akhter, Kaifi Azmi, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Khawaja Ahmed Abbas, and Manto etc. to spread the message, so to say. The film songs took the poetry and stories of these poets to the man in the street.

It is debatable whether the people were affected in any intended and positive sense but it certainly did raise the general level of poetry and scripts. Film poetry was no longer considered an enterprise of failed poets who wrote poetry for films because they were hardly recognised as front rank poets by the literary community itself.

The partnership between Sahir and Burman started with Naujawaan in 1951, became popular and acceptable with Baazi and ended with Pyaasa by the end of the decade which many consider to be one of the best films made by the popular Bollywood industry. Its outstanding lyrics by Sahir are composed in equal measure by S.D. Burman and some of the greatest numbers were created.

Unfortunately the two fell out quibbling as to what came first, the word or the note. Sahir was very particular about his or the poet’s name being mentioned in the same breath as the composer and the vocalist. He insisted that the name of the poet too should be printed on discs, gramophone records and announced on the radio because the name of the vocalist and that of the composer were done so.

There was a time when no name was mentioned -- of the composer, vocalist, lyricist but only of the name of the character in the film on which the song was picturised. Lata Mangeshkar took strong exception to it in the late 1940s and early ’50s and since she became so popular in a short span of time her wishes could not be ignored by the radio walas and record companies. Sahir also wanted equal payment to what the vocalist got and he was so popular that it was acceded to as well. So he got in thousands while in the earlier phase the poets were given a pittance or just told to come another time.

After the falling out, Sahir wrote for other composers like Roshan, Ravi, O.P. Nayyar and Jaidev while S.D. Burman continued to compose film songs till the very end. If anything, the loss was that of the final output. It must be said that the film songs have enjoyed an autonomous status heard by those who have no idea of the film, the situation or the character. The rich heritage of music in the subcontinent secured this autonomous stature of the film song and it survived the films in which it was meant to serve a specific purpose. The film songs have been heard for their own sake by successive generations all over the world.