None of the early amendments to the constitution was to grant more democratic rights to people. The aim of these amendments was to curtail judicial powers and destroy any possible opposition to the federal government

In 1958, National Awami Party had been a favourite to win the first general elections in both East and West Pakistan; and that was one reason why the elections were never held and martial law was imposed. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was trying to curry favour with the likes of Maj-Gen Iskander Mirza and General Ayub Khan, the National Awami Party was trying to raise the flag of democracy, secularism, and provincial rights.

Though NAP had seen a split in 1967 when Maulana Bhashani and Wali Khan formed their own factions after the separation of East Pakistan, the Bhashani faction had become irrelevant in the rump Pakistan. Now again in the 1970s, against Bhutto’s repression and violations of fundamental rights, NAP -- led by Wali Khan -- was the only progressive force in the Pakistan that was being steamrollered with constitutional amendments.

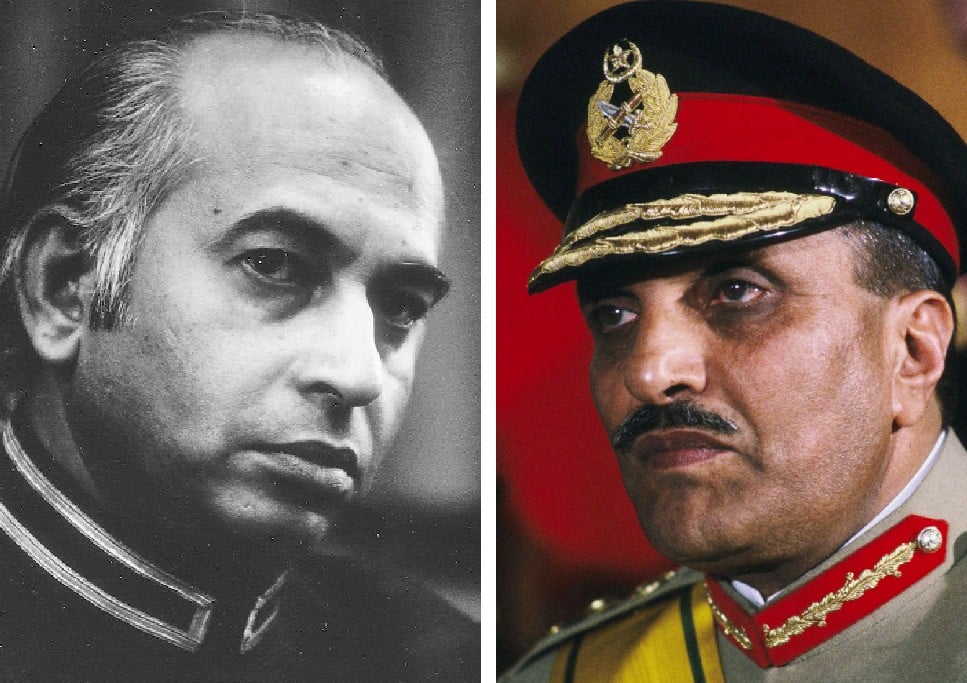

Being himself from a smaller province, Sindh, ZA Bhutto could and should have understood the aspirations of other smaller provinces i.e. Balochistan and the NWFP (now KP). Instead, Bhutto stood by the Big Brother and tried to draw his strength from the army and from his own creation of 15,000-strong Federal Security Force (FSF). In addition to Balochistan and the NWFP, Wali Khan was also popular among the progressive forces in Punjab and Sindh, and Bhutto did see him as a major political threat.

With NAP banned and all its properties and funds forfeited to the federal government, the true meanings of the amendments came to the fore. While drafting the amendments, Bhutto had carefully selected every word to support his future actions. He was bent upon destroying democratic forces that could stand him in good stead against anti-democratic forces that ultimately toppled him.

When the case was heard in the Supreme Court of Pakistan, the then Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman -- who had earned a respectable name in his judicial career and as head of the Hamoodur Rahman Commission -- for some mysterious reasons overruled Wali Khan’s objections against two judges on the bench who were well-known for their proximity with ZA Bhutto.

It is surprising that a judge of Rahman’s caliber -- who himself hailed from East Pakistan and had closely observed the consequences of declaring political leaders as traitors -- was unable to see the ruse in Bhutto’s machinations. It is even more startling that -- even if Wali Khan and some of his colleagues were deemed to be sentenced -- the entire political party that had had an illustrious background in the struggle for the restoration of democracy against military dictatorships when Bhutto had been in collusion with both Generals Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan was terminated with ruthless force and Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman upheld these actions.

Whereas the Supreme Court’s acceptance of press reports and intelligence officers’ statements as admissible remains questionable, the court’s observation that Pakistan comprised just one nation and did not have any nationalities was purely a statist and centrist prejudice, especially when Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman himself had investigated the fallout of such assertions in East Pakistan. He tarnished his own image with this last major judgement of his otherwise impressive career.

There was not even a single note of dissent. All judges were unanimous that NAP was indeed a threat to this country. One wonders how Wali Khan could be released within weeks after ZA Bhutto’s removal by General Ziaul Haq -- a self-proclaimed defender of Pakistan ideology.

Just two days after this verdict, Justice Hamoodur Rahman retired and Justice Yaqub Ali was sworn in as the new chief justice of the Supreme Court.

As if all this was not enough, ZA Bhutto introduced the Fourth Amendment to the constitution further curtailing the writ jurisdiction of the High Courts under Article 199 in cases of preventive detention. Now the courts were not allowed to grant bail to a person or to prohibit such detention. A presidential ordinance was promulgated that disqualified NAP office-bearers from membership of national and provincial assemblies. With a parallel ordinance special courts were established to try anti-state activities.

After these changes, no high court had the jurisdiction to come to the aid of political victims and could not grant such people bail during detention. The whole process of the Fourth Amendment was so cunningly handled that the other two elements of the amendment were projected to dilute the more destructive ones: six special seats to the minorities were allocated in the National Assembly; and in Punjab Assembly minority seats were increased from three to five.

The opposition members who wanted a discussion on the Fourth Amendment -- especially regarding the curtailment of high court jurisdiction -- were physically removed and almost defenestrated by the security staff. The opposition leaders who had this distinction included big names such as Maulana Mufti Mahmood, Prof Ghafoor Ahmed, and Mahmood Ali Kasuri. After their defenestration, the Fourth Amendment was passed without any opposition. Interestingly, the PPP majority could have passed the amendment even without such mean tactics, but probably it had to become part of our history.

The Fifth Amendment was introduced in September 1976, amending 16 articles and the First Schedule of the Constitution. This amendment further restricted the powers of the high courts under Article 199. Now for the first time the judges themselves were affected by these changes in several ways: the term of the chief justices of supreme and high courts were to be determined not solely by age but also by a fixed period as an alternative. Now it was evident that ZA Bhutto wanted to secure changes in some of the appointments.

Another provision of this amendment was that now the government had the power to transfer a judge -- without his consent -- from one high court to another and no reason had to be given and no consultations in this matter were required even with the chief justice.

Again, this amendment bill was also sugarcoated with the establishment of separate high courts for Sindh and Balochistan, and that was projected more prominently than the restriction on the high court jurisdiction to grant interim bails. Abdul Hafeez Pirzada was federal education minister in ZA Bhutto’s cabinet. He vociferously attacked judiciary for encroaching upon the legislative and executive functions. He was of the opinion that if the judiciary deviated from the constitution it would be subversion and high treason. Even ZA Bhutto himself announced on the assembly floor that an independent judiciary did not entail its supremacy over other organs of state.

With this amendment in place, the judges were constantly under threat of transfer if they did not oblige the government functionaries. Now even the chief justices of high courts could not refuse elevation to Supreme Court for fear of compulsory retirement. Though it was the only amendment passed in 1976, the Fifth Amendment totally subdued and tamed the superior judiciary. The chief justices of Lahore and Peshawar High Courts -- Sardar Iqbal (father-in-law of Ayaz Sadiq) and Ghulam Safdar Shah -- were forced to quit after completing their four-year term even when they had not reached the age of superannuation.

After Justice Sardar Iqbal’s retirement, Justice Maulvi Mushtaq was the most senior judge of the Lahore High Court but ZA Bhutto bypassed him to appoint his favourite Justice Aslam Riaz Hussain as the Chief Justice. This favouritism cost Bhutto dearly when Justice Mushtaq used insufficient evidence to sentence Bhutto to death after his removal from power by General Zia.

In 1977, the last two amendments were introduced by ZA Bhutto; the Sixth Amendment in January, in the last session before the general elections; and the Seventh Amendment passed by his new and controversial assembly in May, as a last-ditch attempt to save his government.

The Sixth Amendment was specifically brought in for giving a chance to Chief Justice Yaqub Ali to continue after his superannuation. Through this amendment, ZA Bhutto blatantly made a mockery of the constitution: not long ago he himself had deprived the judges of their chance to continue after completing their four-year term as chief justice even if they were as young as just 55; and now Bhutto wanted to allow Justice Yaqub Ali to continue after the age of 65, on the pretext that he had not completed his term as the chief justice.

The amendment was passed and Justice Yaqub Ali continued as chief justice, only to be removed by General Zia, when he overturned the amendment to appoint his own favourite Justice Anwarul Haq so that he could get the decisions that he wanted.

The Seventh Amendment made provision for a referendum since Bhutto did not want a reelection after the opposition rejected the results of March 77 general elections. Bhutto could neither hold a referendum nor a reelection, for General Ziaul Haq toppled him in a bloodless coup on July 5, 1977.

Now General Zia would start his own mutilations of the constitution; but the fact remains that Bhutto himself mutilated his own constitution as much as he could and as a result antagonised all his potential companion in the journey to a stable democracy. It is a sad reality that none of the early amendments discussed above was to ensure or grant more democratic rights to the people. The aims of these amendments were to curtail or restrict the judicial powers and to destroy any possible opposition to the federal government.