A forty year record of the achievements of Sheikh Sharif Sabir, the great Punjabi scholar, researcher, editor, poet and lover of language

Sheikh Mohammad Sharif Sabir, the great Punjabi scholar, researcher, editor, poet and lover of language passed away on October 1, 2015 at the age of 87. His landmark work of editing Heer Waris Shah made him renowned in both West and East Punjab. It took him over ten years to complete this work. Earlier, he had already written a book of poetry and edited Pooran Bhagat of Qadiryar, and translated parts of Gulistan and Bostan of Sheikh Sa’adi into Punjabi. He edited Sultan Bahu’s poetry collection Abiat-e-Bahu, the monumental work of Mian Mohammad Bakhsh Saif-ul-Maluk, the poetry of Bulleh Shah and had just completed editing of the poetry of Baba Farid before his demise. Being also a scholar of Persian and Arabic, he undertook a Herculean translation of Data Ali Hajweri Gunj Bakhsh’s Kashf-al-Mahjub from Persian to Urdu. He was commissioned by the Auqaf Department.

The early eleventh century Persian of Data Sahib and the associated matters of religion daunted even the world-renowned Persian scholar Nicholson who had left some parts untranslated. There were some obscure idioms and complicated matters of Shariah but Sharif Sabir managed a complete translation in six years.

Funding is always a major problem for publication of Punjabi books. His other three major works on Bulleh Shah, Sultan Bahu and Mian Mohammad Bakhsh’s Saif-ul-Maluk (as mentioned earlier) were sponsored by Syed Ajmal Hussain Memorial Committee.

I had the honour and pleasure of knowing him for forty years. His simple rural background and job of an ordinary school teacher never handicapped him socially. He was lively and humorous and was the best company if you shared his love for the language. His bicycle kept him mobile and he would mysteriously disappear once the matter in hand was done. "Master Sahib, where did you disappear yesterday evening when I got up to fetch a pen? " I rang up his home and "We had concluded the discussion!" was his stock answer.

He always carried his satchel with the current project in hand and would start reading and writing when the company he was in was engaged elsewhere. The subjects were always academic, primarily of language, whether it was Punjabi, Urdu, Persian or Arabic. Every aspect of language interested him .With his Auqaf Department connection, he also got a chance to lecture at the Quran Academy. A student once thought he should test him. "Sir, will Ganga Ram go to heaven?" "Yes!" said Sharif Sahib, "if you study the Book carefully, you will get the answer and the answer is yes."

He had the sensibility of a nineteenth century man. He was singing or composing in his head while others prattled away. He would be tapping whenever there was music playing in the background.

He was never pretentious about his knowledge or work. "I have done some plumbing over this verse and you may read it thus." Sometimes, this plumbing could get venturesome and if the other party was contentious, he would say, "I will do some mantras (taweet dhaga in Punjabi) and get back to you."

Normally the mantras were done in the company of Najm Hosain Syed, whose opinion and company he always sought. But he did not always agree with Najm Sahib.

His liveliness was best known to his students in the class. He would sing and clap and even dance if the lesson could be rhymed. His student Nisar recalled how he would dance and rhyme while teaching English to students of class five. While teaching English to elementary classes, he privately did a Masters in Persian and went on to teach Persian and Urdu at Lahore’s Central Model School. He was promoted to be a language specialist and taught at the Central Training College before his retirement in the 1980s.

He was happily married and was a loving husband and a caring father. He doted on his four sons and two daughters. One of his bright and handsome sons committed suicide. Only a stoic like Sharif Sahib could withstand that shock. "He did what he wanted with his life. We are to be blamed for not knowing his mind and its pain." Of the other three sons, one went on to become a colonel, another a professional banker and the third an engineer. Daughters are happily married too. But like many middle-class children, they emigrated to the United States of America. Last year, they took Sharif Sahib there. He would make long phone calls to me, saying "Colonel Saab please get me out of here." When I asked him where would he live, he said, "I will go back to my village". He was talking of the village that he left nearly seventy year ago.

None of his close relatives was alive, yet he came back a few months ago. He was working on what was to be his last project -- the poetry of Baba Farid. As most of Baba Farid’s more authentic poetry is found in Granth Sahib, no Sikh source could help in editing; they cannot change the words of their Holy Book. He wanted to contact my Sikh friends in New York but I warned him against it. "What is the harm in discussing?" "They might kill you Sharif Sahib." Defying death, Sharif Sabir did it and the book is already in the press.

Death finally caught up with him in the village when he developed a chest infection. He was brought to Fatima Memorial Hospital in Lahore but it was too late. His attendant told me I could come and see him but that he does not recognise people nor can he speak. I took Najm Hosain Syed Saab along. He uttered "Achha!" and then started crying. But this was not the enthusiastic lively "Achha!". He passed away later that night. He was buried near a friendly saint’s tomb in Narang Mandi. May God bless his soul.

Since his area of work was popular classical literature, he had many critics especially after Heer Waris Shah which nobody had touched earlier except Sheikh Abdul Aziz Bar at Law. The latter edited only by giving his preferred text from a comparison of various earlier editions and attempted no modification or correction of his own. There was a major problem of spellings after the changes in some letters by Fort William College in the Urdu script. The new spellings opened more than one possibility.

And where angels feared to tread, many fools rushed, in adding their own lines. The popular edition of Asli tay waddi Heer (The Real and Master Heer) was of Piran Ditta of Targad Wali. It is still the most sung of whatever little singing of Heer is left. From my childhood in the village, like everyone else I would hum Doli chadian maarian Heer cheekan, or Gia bhaj taqdir day naal thootha or Heeran wich jahan day lakh hoyan. All these passages were Piran Ditta’s own. He added religion and sentimentality which were popular obscurantisms. If I ever reported these critics, Sharif Sabir would say, "Let us see the other plumber’s work. Keep a note of these". In one exceptional case, he accepted the change by saying "This man knows the mantra".

The critics have not been generous though. People did not know much about Sharif sahib’s background or knowledge. He held no office and won no award worthy of his calibre.

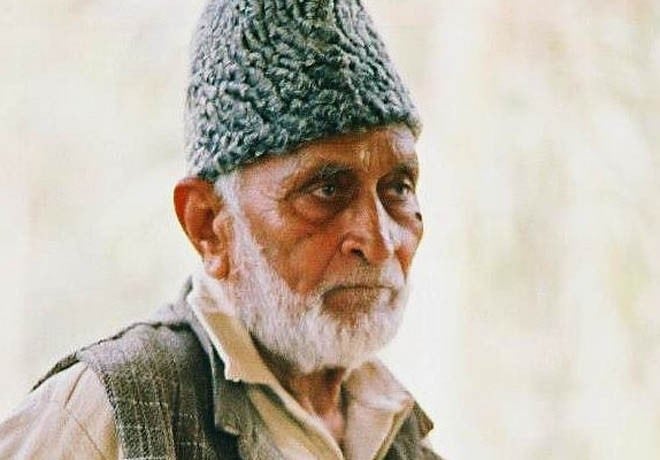

Sometimes a picture does capture a man. This portrait of Sharif Sabir by Akram Warraich moves me to tears. The real Sharif Sabir never stood up; he did not have the time and was too busy teaching. Do you see a caged lion in this portrait? That’s him.