Narrating the tragedy of Karbala in various forms

Among the major poets of Urdu, the one who got closest to drama was Mir Anees in his marsiyas. It would be erroneous to call his poetry, his greatest works, as drama. At best, these can be called dramatic narratives, in the tradition of the dastaan, the form this region was more familiar with. Critics like Zahida Zaidi have pinpointed the dramatic elements in his poetry, yet falling short of calling it drama.

The dastaango was primarily one person, who narrated the dastaan and in the course of that narration assumed the roles of the various characters. He had great facility with the text or he had a memory that was sharpened to retain vast amounts of material with the ability to move from one role to the next while also holding on as a narrator to the basic thread of the tale.

Generally, among the Muslim world during the medieval period theatre was not patronised by the courts. It was only with the growing European influence in the eighteenth and nineteenth century that theatrical activity as we know in the current sense picked up in those lands. India was no exception to this general trend.

After the gradual demise of the Sanskrit Theatre, the many aspects or parts of the theatre were incorporated into religious ritual. For centuries Ram Lila and Ras Lila quenched the thirst of theatre through the high dramatics of the enactment of tales or episodes from religious mythology. With greater European influence, theatre in its more formal sense was instituted in the port cities of Calcutta and Bombay. The influence of the growth of theatre on music and the other art forms in the heartland of Delhi, Lucknow, Banaras has not really being properly measured. Many of the top ustads like Abdul Kareem Khan two timed in his fast changing cultural scenario. They on the surface remained great ustads while moonlighting in the more lucrative environs of the professional theatre.

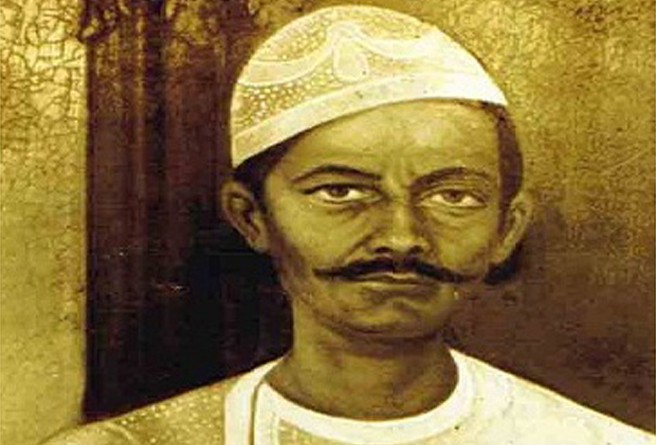

But it is known that Wajid Ali Shah, deeply interested in theatre, wrote and had plays staged under his patronage in Awadh. He must have continued with his interest once he was imprisoned in Matya Burj outside Calcutta, adding a very rich strain to the evolving culture of Bengal in the nineteen century. Playwrights like Amanat Luchknavi, hailed as the first playwright of Urdu with his Indar Sabha, were not even considered worthy of any attention by the practitioners of high poetry like the ghazal, masnavi, and the musaddas and rubai. These were seen either as failed poets or tukbands who had found an outlet in a lesser genre like theatre.

It is likely that Mir Anees was exposed to this theatre and he may have borrowed aspects or parts of it. Still he did not aspire to write a play on the tragedy of Karbala, building on the elements of the dramatic narrative form embedded especially in the masnawi and musaddas poetic poems. He did not travel much either, probably only journeyed to Azeemabad and to Hyderabad Deccan and it is not known whether he went to any of the growing port cities where a more polyglot culture was taking shape under the patronage not of the royalty but the new mercantile class.

The question has often been raised as to why great drama has not been written here and the answers are many and some quite intriguing. According to Allama Iqbal, drama could not be written because it embodied a process of depersonalisation while the entire stress of our traditional heritage had been on the empowerment of the person. Iqbal himself was against drama because he thought that it did not let the writer or the protagonist retain his singular integrity. The greatest quality in a playwright which in the eyes of Keats was negative capability became a disqualification in the eyes of Iqbal.

To many critics drama can only be written if there is a fundamental conflict and because there is none in our society, real drama has been held in low esteem even by the poets and writers themselves. The origins of drama in the West was in Greece where they based their tragedy on a fundamental conflict which defied a resolution, and the resolution, if any, sharpened the various levels of contradictions which were inherently irreconcilable. In our society, in the face of the conflict resolution based on the tenets of religion, the conflict has never attained that cosmic universal character. Drama draws its sustenance from a conflict which is actually a pseudo conflict, at best a test of will, of determination and of sincerity. The passing of the test restores the balance, and if it does not, then the fault lies with the character, his inadequacy and lack of capability. It is the weakness of character, interpreted as the machinations of the devil or the victory of the evil; in which case drama becomes an instrument of reform. In the middle Ages in Europe, this kind of theatre was called the Morality Play. The other types prevalent then were the Miracle Plays and the Passion Plays, all emphasising the primacy of some religious value.

In the Muslim World there has been a problem with presenting religious figures on stage; actually even the pictorial representation has been shrouded in great controversy. It is said that in Iran some kind of a theatre with actors took place where the entire battle was enacted. Called Tazia, (different from the replica of the mausoleum that is known as Tazia in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent) it was a celebrated form that continued well after the end of the Safavid rule into the reign of the Qajar Dynasty. A kind of a Passion play, it was seen by many as atoning for the sins and excesses committed. In the Indian sub continent Passion play is without the personages in the shape of actors, it is all a symbolic representation which falls more in the realm of poetry than theatre.