He became the interpreter of Iqbal's worldview, and chose to be slightly on the liberal side of the hordes of interpreters, who rode the bandwagon of Iqbal, especially after the creation of Pakistan

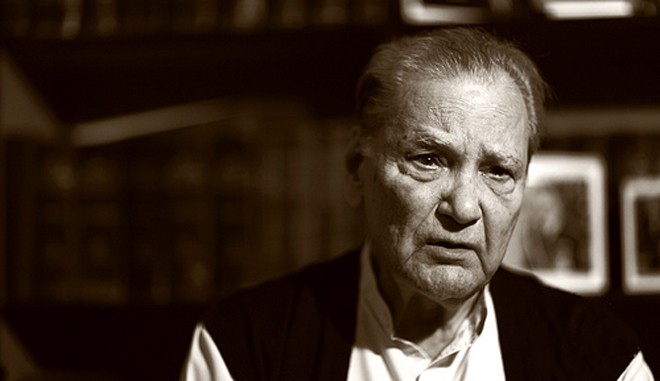

All his life, Javid Iqbal struggled to move away from the very long shadow of his father. He was not a run of the mill scholar but the flowering of his scholarship was always cankered by the unbearable pressure of conformity that this society exerted on him.

It should not be forgotten in the first place that the instant recognition that he received and the focus of attention that he became was also because he was the son of Allama Muhammad Iqbal. All eyes were on him because the elder son of Iqbal, Aftab Iqbal, had developed deep differences with the father that were also reflected in him espousing an ideological position that was different.

The problem with Iqbal has been that there are many Iqbals -- one the official Iqbal, the other Iqbal who is unrehearsed, and for the family yet another Iqbal who is the father, also the father to a son whose mother he left. He is principally a poet and poets defy conformity and relish in abandonment. But Iqbal deified as a buzurg had to use poetry as a means of disseminating a message.

Javid Iqbal progressively became the interpreter of his father’s worldview, and to the relief of many, he chose to be slightly on the liberal side of the hordes of interpreters who rode the bandwagon of Iqbal, especially after the creation of Pakistan. They relentlessly hammered him in shape in accordance with whatever shape they desired the new social order and the state to take.

This was a great disserve to the man (Iqbal), who broke a few taboos in his life, and wanted the Muslim comity, especially in the Indian subcontinent, to be forward looking; ridding itself of the chains of taqleed that sanctify blind following of what the elders or predecessors had chosen for themselves.

Javid Iqbal as he wore on in years also became bolder and championed the Iqbal who took the initiative of propounding ijtehad, a path of discovering and finding new solutions to new problems that inevitably emerge in a fast changing world. The older solutions did not appear to be relevant or applicable and so newer answers were required.

Iqbal took the revolutionary position of opting for the nation-state as a possible solution than to side with those wanting to migrate to lands of Muslim rulers, those who wanted the revival of caliphate and those who wanted an independent India retraced on the lines that had obliterated with the end of Muslim rule in the subcontinent. Those solutions of the past which refused to link territory to peoples’ struggles living in a certain area was what rendered their politics ineffective. Espousing the democratic ideal was the natural consequence for arriving at people’s verdict and it had to replace the religious revolutionary/fervour touted as the only legitimate means of decision-making in all fields.

He was a good writer of prose and many who took part in plays on radio or heard them testify to Javid Iqbal’s ability to pack enough tension to become an effective piece of drama. But after a while he abandoned that route and took to writing prose pieces that were quasi-philosophical, quasi-aesthetic and quasi-political in character.

It became difficult to pin him down as a writer. He was encyclopedic and wholesome, more in the manner of a sage, who presents a well-rounded viewpoint in totality rather than concentrate on the affirmation of a certain specialised vision.

Like his father, he also took a few steps in active politics, and like the father, he was not successful as a political activist, rather more as a political thinker. He got a few thousand votes against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s overwhelming numbers.

When elevated to be a member of the higher judiciary from where he retired after serving his terms in the High and Supreme Courts, he was not remembered as a very innovative judge and his judgments do not stand out as breaking new ground.

Some of his own thoughts about the fast changing world can be garnered from the number of questions that he posed to his late father in his autobiography Apna Gareban Chaak, that he wrote in the last few years, but he was not able to expound a whole worldview because of the limits set by being the son of Iqbal. Whatever he did, it got merged into the larger picture of what the father had said or wanted and at best became an interpretation or an explanation of the father’s position.

Iqbal Studies too suffered because it has been aligned to a state, the state that progressively became more conservative in its outlook, albeit with spurts of great liberal phases. But, on the whole, it was meshed in the crisis that is principally intellectual and is now surfacing as a political one in most of the Muslim world.

As he grew in years, he became less circumspect about his views on religio-political outlook and took up positions that he was not really known for in his early life. It could also be that the entire tenor of society had become so conservative and backward-looking that some position relevant to the spirit of the age had to be taken.

It was different during the 1970s, when a liberal position seemed reactionary in an age ablaze with socialist zeal. But though he spoke for social justice, he stayed a studied step behind in his view about the revolutionary change mouthed a dime a dozen by many timeservers. He spoke for much that was cultural in nature and hence of common roots and heritage, and sided more with those wanting an inclusionist approach than one that drum beat the second coming of the past greatness of Islamic civilisation. He was too well-read and informed about being self-certain.

In these difficult times, mired in zealotry, his voice was one that advocated tolerance and large-heartedness as against narrowness fired by self-righteousness.

The article has been updated to reflect the correct spellings of Javid Iqbal.