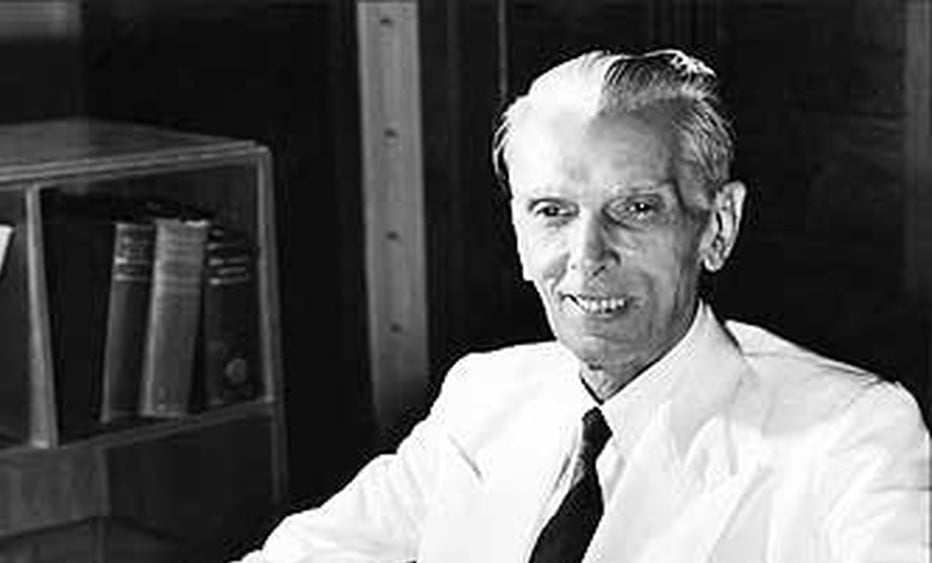

What was Quaid-i-Azam’s vision of Pakistan?

Of the several enduring issues that plague Pakistan since the Independence, one is the persistent failure to grasp the notion of Quaid-i-Azam’s Pakistan. The questions that rattle us are: What sort of Pakistan did the founding father envisage? Was Pakistan meant to be an Islamic polity with shariah being the supreme law of the land? Or, was it destined to be a secular state with a Muslim majority?

These have led to dichotomy of opinions among politicians, political commentators and common Pakistanis.

For people on the right, Pakistan was meant to be an Islamic polity, a country destined to be ruled according to Islamic shariah. "What Pakistan means? There is no God but Allah," is still a popular political slogan. The Rightists root their argument in history leading up to the founding of a new state in 1947. They point to the communal base of All India Muslim League (AIML) -- a political party responding to the needs of Indian Muslims, the party’s invoking of Islamic slogans -- "Islam in danger" and among others Jinnah’s several speeches anchored in Islamic imagery.

In his speech on March 23, 1940, the historic session of Muslim League at which the resolution for the creation of Pakistan was passed, Jinnah remarked, "the Hindus and the Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literatures…Very often the hero of one is a foe of the other…" On March 22, 1940, in a strong communal language, Jinnah opposed any independence which bestowed a permanent minority status on Muslims.

Referring to Hindus numerical superiority vis a vis the Muslims, "three to one," he said, "We come back to the same answer: the Hindu majority would do it, and will it be with the help of the British bayonet or Mr. Gandhi’s ‘Ahimsa’ [strategy of nonviolence]? Can we trust them anymore?" Jinnah’s reply was a clear no.

Responding to Gandhi’s notion that Hindus and Muslims were brothers, Jinnah noted, "The only difference is this, that brother Gandhi has three votes and I have only one vote."

"Islam in danger," was the league’s slogan during the 1945-46 elections in Punjab. It relied on support from pirs to issue fatwas that anyone who did not vote for league would cease to be Muslim. Such political opponents as the Unionist Party Prime Minister Khizar Hayat Tiwana were branded as infidels and traitors to the cause of Islam.

However, liberals entertained a different world view. For them, Jinnah had envisioned a pluralist Pakistan, one where irrespective of one’s religious position one will be the equal citizen of Pakistan. To them, Jinnah’s western lifestyle and his several speeches preceding Pakistan and afterwards bear testimony to the effect that he perceived Pakistan as a Muslim majority state and a secular democracy.

Speaking in the wake of Macdonald communal award in August 1932, Jinnah viewed Indo-Muslim differences through political prism only. "Religion should not enter politics", he said. "This is a question of minorities and it is a political issue", Jinnah observed.

Similarly, on August 11, 1947, in his presidential address to the constituent assembly of Pakistan at Karachi, Jinnah said, "you may belong to any religion or caste or creed -- that has nothing to do with the business of the state …Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is their personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state," Jinnah continued.

This article advocates not taking Jinnah’s messages on face value. Leading us astray, these messages lead us to a confused Pakistan which we live in since the Independence. That even after 68 years, we cannot decide what Quaid-i-Azam’s conception of Pakistan was. In fact, the founding father’s objective was the creation of a Muslim majority state where the community’s socio-economic and political interests could be secured. The means he adopted to realise his goal were often contradictory. Since Muslims were a disparate lot -- religious and secular, feudal and middle-class -- uniting them required Jinnah to deliberately employ vague and often contradictory messages.

A pragmatist politician, Jinnah valued the end more not than the means he employed. In the end, overcoming a bewildering array of challenges to his dream, Jinnah won us Pakistan. Once independent, the diverse lot of people demanded the kind of Pakistan they believed Jinnah had promised them. Then the reality betrayed everyone in Pakistan. Today’s Pakistan is neither a religious polity nor a secular state. With opposite forces, it has become a concern for every citizen.

Perhaps, presently, our salvation lies in revisiting Jinnah’s perception of Pakistan, which demands us to move from a subjective reading of our history to an objective analysis.

In a final analysis, Jinnah did not envision a shariah state though he would not have objected to the state to be influenced by religion.