From a two-room school in a Sindhi village to the pinnacle of education, a step by step account of Ibrahim Joyo’s educational journey

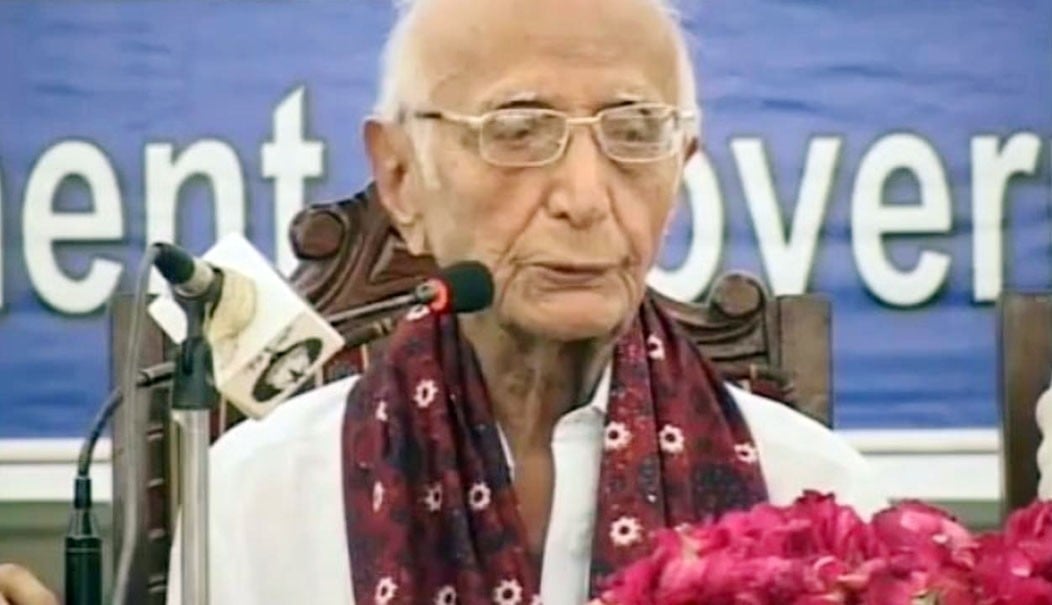

Recently the 100th birthday of Ibrahim Joyo was celebrated and glowing tributes were paid to him. After the death of Sobho Gianchandani last year, Joyo remains probably the only eyewitness to the events of 1920s in Sindh. A lot has been written in the Sindhi press about his life and achievements but the mainstream media -- both print and electronic -- has overall remained more involved in stories about Ayan Ali and DJ Butt, hardly having any time and space for intellectuals of Joyo’s caliber.

Rather than narrating the course of his life, one is more inclined to draw some lessons from Joyo’s adventures in education in the pre-partition India. What is it that inspired him? How the teachers and head-teacher worked? Where did Joyo spend his time as a student? When did the decline set in? And, who was responsible for that?

Those who are interested in all aspects of Ibrahim Joyo’s life, may read a comprehensive book by Mazhar Jameel, Ibrahim Joyo: Aik Sadiki Awaz. Though the book is repetitive and spans over 750 pages, it is probably the most detailed account of his life and times so far.

On Joyo’s education journey, we begin with his first teacher in school, Tekan Mal, a Hindu young man who lived around 20 miles away from the school. The school was in Joyo’s village, Abad, near Kotri in present-day Jamshoro district. In a marvelous sketch of his teacher, Sain Tekan Mal -- My first teacher, Joyo writes with relish about his first mentor, who shaped Joyo’s childhood in a form that not many teachers of today can even think of.

From Joyo, we come to know that the two-room school was a garden for his teacher where he planted seeds of knowledge and nurtured the minds of his students. The teacher would leave for his village on Saturdays, and come back on Monday mornings, always laden with different types of sweets and a host of bread and other confectionaries for children at school. He would tell his pupils about how Amma (mother) had prepared gifts for them. The teacher would also bring some herbal medicines, prepared by his father back home, to school and would always keep some concoctions to cure cough among children and some ointments to treat any cuts and bruises. The teacher’s benevolence was not confined to his school alone, the entire village benefited from his generosity and humanity.

We are talking about a village in Sindh in 1920s, where a teacher becomes a role model for his pupils by his complete dedication to his school and its children. The school had only the first four grades, mostly focusing on literacy and numeracy with only a couple of textbooks. Every week a barber would come to school for children’s hair and nail cutting and would offer sweets in exchange for good behaviour while he did his job. If children had dirty teeth, they would be given Miswak -- a tree twig for teeth cleaning.

Since there were no ballpoints or fountain pens, the teacher would carve out pens from reed for his students and teach them how to sharpen them, a masterful craft in its own right. In addition, making black ink from lamp soot was another skill imparted by the teacher who would mix appropriate amount of water in the soot collected by each pupil at home over a period of days. The resultant paste would be dried into a powder which in turn would be made into ink. The teacher would call each student to check the written work and then write a new lesson for each of them separately. The only language that was taught at school was Sindhi and the teacher would spend extra time with slow students after the school hours. There was no homework and no burden of books and copies. Appropriate time was allocated for children’s play and everybody would sleep early and was up at dawn. There was no uniform and hardly any pupil had shoes.

Once in a while the teacher would take his pupils on a picnic to the river or to the Kirthar Mountains. The picnic was not only fun but also a learning experience as Tekan Mal, the teacher, would explain the water management system of rivers and canals. Similarly, the teacher would show his pupils various types of stones and talk about their similarities and differences.

According to Ibrahim Joyo, his Hindu teacher would teach less from the textbook and more from the everyday life experiences. He would stress that all human beings should be respected and treated well, be it a prince or a pauper.

Joyo passed his fourth-grade exams in first class and two books were presented to him as a gift from the Department of Education; one was a book of moral stories and the other was the Mirza Qalich Baig’s Sindhi translation of a German book, Basket of Flowers. Tekan Mal was so proud of his student that he kept telling everyone about his student’s achievements.

Then after one year at another school, Ibrahim Joyo was taken to Sann where GM Syed had established an Anglo-Vernacular (AV) School that combined Sindhi education with English language teaching and did not charge any fee. In 1927, Joyo started his AV School in Sann where the head master was Paras Ram and the class teacher was Faiz Muhammad. Joyo speaks so highly of his teachers at AV School in Sann that one feels like visiting that alma mater of Joyo. In addition to Sindhi and English, there were options such as Arabic, French, and Persian. GM Syed had also opened a centre where Arabic and Persian were taught without charging any fee. During summer vacations there were extra classes for students who could not perform well in exams.

GM Syed would invite intellectuals such as Mirza Qalich Baig and Fateh Muhammad Sehwani to his school where they would interact with children and leave a lasting mark on them. Joyo recalls that whenever GM Syed would go out of Sann, on his way back he would bring sports kits or pencils, copies and caps for children.

GM Syed facilitated Joyo to get admission in Sindh Madrasa-tul-Islam (SMI) where, based on his performance, he got full scholarship. In the library, he had full access to English, Persian, Sindhi, and Urdu books which quenched his thirst for knowledge and learning. At an early age, he read many of the classics of world literature. Joyo spent four years in SMI and obtained first class second position in his matriculation examination conducted by Bombay Board. It is worth mentioning here that after occupying Sindh, the East India Company had placed Sindh under the command of the governor of Bombay, as Sindh became part of the Bombay Presidency.

After Joyo’s matriculation, his grandfather wanted him to start a job but again GM Syed came to his rescue and arranged for his admission to the DJ College, Karachi. The DJ College had been established by a philanthropist, Dayaram Jethmal, who was a renowned lawyer of his time and later also became a judge. His brother, Mitharam, had built a hostel for students which is still famous in Karachi as Mitharam Hostel.

The college had a competent principal, Narayndas Bolchnad Bhutani. Joyo’s subjects to study were political economy, civics, world history, logic, and philosophy. In addition, he also opted for advanced studies in English and Persian languages. The faculty at the DJ College had dozens of scholars such as Hotchand Mulchand Gurbaxani (1883-1947), a novelist and an expert in Persian language as well as a connoisseur of Shah Abdul Bhittai’s poetry; Prof TM Advani who later became vice chancellor of Bombay University; Prof LH Ajwani, an essayist of repute in both English and Sindhi, and author of a History of Sindhi Literature; Prof Mangharam, author of Sindhi Nasur ji Tarikh; and others. With teachers such as these, Joyo was basking in the light of learning. He devoured dozens of books and the best part was the teachers’ emphasis on going beyond the prescribed textbooks, which kindled in Joyo a lifelong passion for reading and writing.

The college was co-education with only 10 to 15 per cent of the class comprising girls. The class was a cornucopia of Christian, Hindu, Muslim, and Parsi (Zoroastrian) students, all interacting with each other, learning about their religious festival and dos and don’ts; respecting diversity and cherishing the opportunity to be part of a college that excelled in harmony and peaceful coexistence.

There were monthly lectures in the college auditorium where renowned personalities were invited to talk about their favourite subjects and participate in a lively Q&A session. Ibrahim Joyo distinctly remembers attending lectures by Mahatma Gandhi, Sadhu Vasvani (1879-1966) -- an educationist who started Mira movement of education, set up in Sadhu Vasvani Mission in Hyderabad, Sindh, and later moved to Pune, India, in 1949. Vasvani preached harmony among all religions and encouraged social welfare activities by students. He believed that no religion taught hatred and there were common strands of humanity in all creeds.

Joyo also became a regular visitor of Theosophical Society lectures and discussions in Karachi. Theosophical Society was initially established in New York in 1875 but later moved to India and Karachi in 1896. It believed in universal brotherhood of humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or colour; and encouraged the study of comparative religion, philosophy and science. Joyo gained immensely from these discussions at the Theosophical Society and gradually evolved into a believer in humanity rather than in any one religion.

The discussions at the society encouraged Joyo to read more; and he read Shakespeare’s plays and the translations of French and Russian literature, history, sociology, philosophy, and most of all he remembers reading History of Intellectual Development of Europe by J W Draper first published in 1864. He also read writers as diverse as from Plutarch and Rousseau to Chekhov and Brecht.

Joyo did his graduation from the DJ College in 1938 with distinction, and the same year joined the Sindh Madrasa as an assistant teacher. After two years, he was sent to do his Bachelors of Teaching (BT) degree in Bombay. At that time every school, be it government of private, was bound to send its untrained teachers to do this two-year course after which the teacher was bound to teach at the same school for at least five years -- failing which they had to pay to the school all the expenses incurred on their degree.

Now we stop to ponder over what we now see in the education sector in Pakistan generally, and in Sindh particularly. Go and try to find a teacher like Tekan Mal, you are likely to find ghost teachers instead; make efforts to locate political leaders such as GM Syed who held education close to his heart, you are bound to meet politicians who run education empires earning billions; use a microscope to detect a college teacher who is a scholar and author, you will at best end up with a teacher having a book of third-rate poetry to his credit; lastly go and look for a college student who has read anything worthwhile about intellectual development.