Every August the themes of Indian Partition and Pakistan’s independence are brought under scrutiny with renewed penchant. This time, too, several articles were carried by newspapers, voicing divergent opinions on these themes. The general tone and tenor of the write-ups was typically ultra-nationalist, as spawned in the media and textbooks. Blinkers of ideology render the viewing of these events as markedly blurred and partisan.

The populist discourse about Partition in Pakistan places the blame and onus of the massacres and pogroms on Sikhs. Books like Khak aur Khoon by Nasim Hijazi provided further credence to Sikh involvement in the communal malady, unleashed in 1946-47. Hijazi’s role in fomenting the communalised sensibility among the Pakistani literati has been immense.

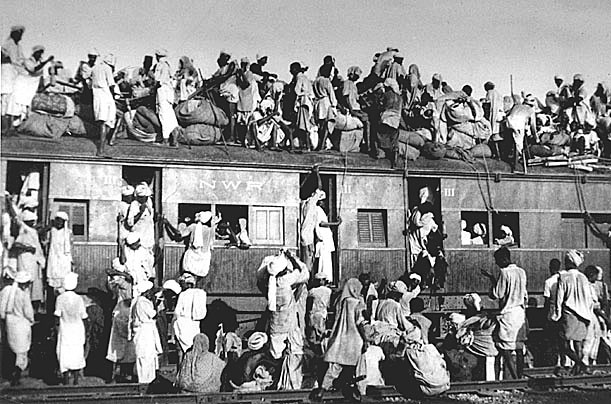

But let us revert to important questions like how did the frenzy trigger off, culminating into one of the biggest genocides in history? That is one of the several questions which is answered differently on both sides of the geographical divide.

Pakistani version underlines Sikh leader Master Tara Singh’s act of brandishing the naked sword at the footsteps of the Punjab Assembly, threatening Muslims with large scale bloodshed in the case of any advancement towards the creation of Pakistan. What led Master Tara Singh to making such a haranguing pronouncement has never been unravelled by Pakistani scholars. Sikh accounts, on the other hand, trenchantly castigate the Muslim League’s designs -- of carving out an Islamic state in which Sharia would be promulgated.

Sikh leaders were particularly incensed because in the socially and culturally plural setting of Punjab, establishment of any monolithic political system would have been catastrophic. In such a case, non-Muslims would be afforded the status of zimmis which obviously was not acceptable to either of the two communities (Hindus and Sikhs). That probably was the perception that led the Sikhs to join Indian National Congress.

Ian Talbot, Nanda and Raghuvendra Tanwar point to the fact that the Punjab was largely peaceful until the ministry of Khizar Hayat Tiwana was allowed to function till early March 1947. Afterwards, the situation deteriorated fast. One can draw an inference that in the multi-communal province like the Punjab, Tiwana though heading the rump of Unionist party, nevertheless, had greater tenacity and acceptance than the parties representing Muslims and Hindus.

Another important question pertains to the impact that the Punjab had to endure of direct action which aggravated the communal tension not only in Bengal but also in Bihar. So far, its repercussions on the Punjab have not been studied in any serious manner.

More important are the Sikh massacres in Rawalpindi and Multan which seemed to have embittered the relationship between the two communities. While sifting through the Mountbatten Archives housed in Harley Library, University of Southampton, I came across many letters of Sikh leader Baldev Singh, addressed to the Viceroy and Governor of the Punjab both, in which Sikh massacres at these two cities are recurringly mentioned. Similar sort of representations were made by Giani Kartar Singh, another Sikh leader from Lyallpur.

One may surmise that Master Tara Singh’s mother was one of the victims of Rawalpindi riots and that partly explains his indignation for the Muslims. Some reports from the British officers strongly suggest that the communal violence in fact started from Rawalpindi/Kahuta and then spread out to the length and the breadth of the province.

However, one cannot turn a blind eye towards the villainous role of the Sikh princely states like Patiala, Nabha and Faridkot that conflagrated the sentiments of animosity between the Sikhs and the Muslims. Patiala state’s army personnel certainly had a role in triggering Muslim Sikh riots in Amritsar which subsequently disturbed the communal camaraderie in Lahore. One horrendous consequence of that tension was the way Shah Alam Market, Lahore (mostly owned by the Hindus) was set ablaze by the Muslims. Besides, some documents in the Mountbatten Archives make a clear reference to the traces of arms and ammunition having been smuggled from Faridkot to Lahore which were later distributed among the trouble-makers.

While deliberating on the gory event of Punjab’s partition, it will be pertinent to underline the proposal of the Sikh leadership. While cognisant of their small number in the province, the Sikhs had put forward a proposal of according primacy to property along with numerical strength of any community. Besides Lahore, they laid claim over Lyallpur (currently Faisalabad) and Montgomery (now Sahiwal) because a big majority of the large landholdings belonged to the Sikhs. These two, the most fertile of the colony districts, were brought under the plough mostly by the Sikh tillers; therefore, they claimed to have a right over these lands.

They also referred to the share of the revenue tax that Sikhs were depositing in the state coffers which, according to their estimation, was far greater in volume than what Muslims had been generating for the British government. Sikh leaders vehemently pleaded before the Viceroy Lord Mountbatten as well as before the Governor Keith Jenkins to give serious consideration to the Chenab Formula while drawing a dividing line. It meant the two divisions of Rawalpindi and Multan were to be handed over to the Muslims where they had overwhelming majority. On the other hand, the Punjab up till river Chenab ought to be conceded to the Sikhs.

All these proposals were obviously not entertained. However, parts of districts of Ferozepur and Gurdaspur were included in East Punjab allegedly to appease Sikhs. Here, too, it is important to note that in Gurdaspur, Ahmadis were counted as Muslims; therefore, the latter constituted a majority by a very small number. Now that Ahmadis have been declared non-Muslims, Pakistani historians should review their stance regarding that particular district. Having said this, Pakistan’s stance on Ferozepur cannot be disputed.

Finally, one may assert that despite sixty eight years having elapsed since the Partition, many questions about that event still need clear and objective answers.