Dear All,

The notorious ‘Cambridge spies’, the highly ranked British luminaries who turned out to be Soviet spies, have had another name added to their number, thanks to documents declassified last week by the British intelligence service MI5.

It all reads like a John le Carre novel really -- first the discovery in 1951 that two highly placed intelligence and diplomatic official Guy Burgess and Don Maclean were actually Soviet agents, then a few years after their defection to Moscow, the discovery and defection (in 1963) of the ‘third man’, their flamboyant colleague Kim Philby, and then the discovery that there was a fourth high ranked spy who turned out to be a leading art historian Anthony Blunt, the ‘Keeper of the Queen’s Paintings’ and recipient of a knighthood for his services (to the arts).

In fact, the British intelligence had known about Blunt’s espionage since 1964 but only acknowledged this officially in 1979 after it was revealed in journalist Andrew Boyd’s book Climate of Treason. The establishment adopted a similar strategy in the case of the fifth member of this batch of spies, John Cairncross. He confessed to investigators in 1964 yet this too was not acknowledged till 1979, after he was directly confronted by journalist Barrie Penrose.

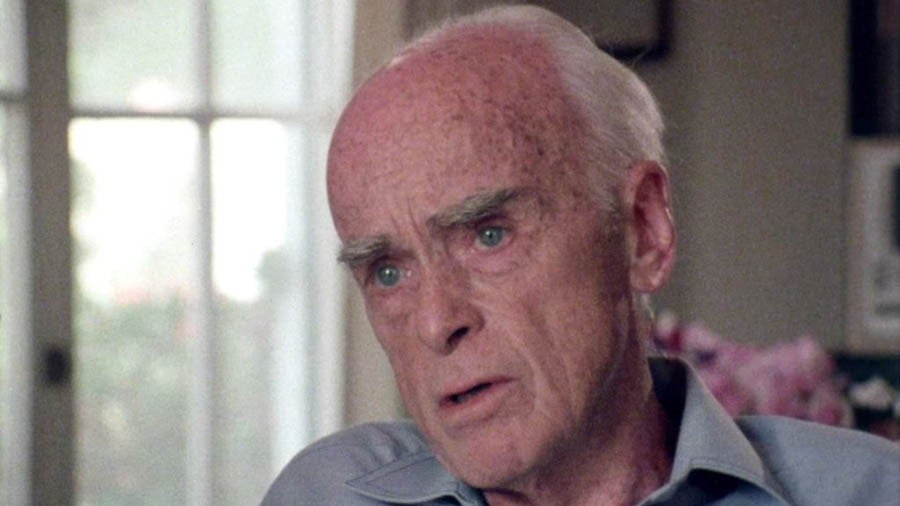

Now, following this recent declassification of documents, another man is revealed to have been a contemporary of the Cambridge Five group of spies: another flamboyant character named Cedrick Belfrage who was in New York between 1942 and 1944 as the deputy "to the most senior British intelligence official in the Western Hemisphere", during which time Belfrage passed on to Moscow information on US and British undercover work.

The interesting thing about Belfrage is that he was a spy "who hid in plain sight": he had been a member of the communist party in the 1930s, had set up a communist paper in the ’40s, and in the 1950s was denounced by the McCarthyite show trials. But when picked up and questioned by the FBI, Belfrage cleverly used the murkiness of his work to his advantage: he admitted that he had passed documents to the Soviets but insisted that he had worked on MI6 orders and that, in fact, the documents had been ‘meaningless bait’.

This double-agent obfuscation was rather clever because when the FBI asked the British for clarification and verification of Belfrage’s claims, MI6 responded by saying it could not give any information on Belfrage as this would go against their intelligence-sharing principles. Possibly, they preferred to avoid embarrassment by not admitting that they had, in effect, employed a known communist sympathiser in their organisation in the US. In any case despite this lack of clarity about his aims, Belfrage was deported from the US and went on to lead a colourful life doing, among other things, work as a celebrity journalist and a much lauded translator of South American fiction. He married five times and died in Mexico in 1990.

The story of the Cambridge spies, the British agents at the heart of the establishment who were actually working for Moscow during the Cold War, just goes on and on. As we get some new revelation every few years we realise that not only are their personal stories utterly fascinating, the way the British Intelligence chose to deal with their own men who had betrayed them with such ease is no less.

The plot thickens…

Best wishes