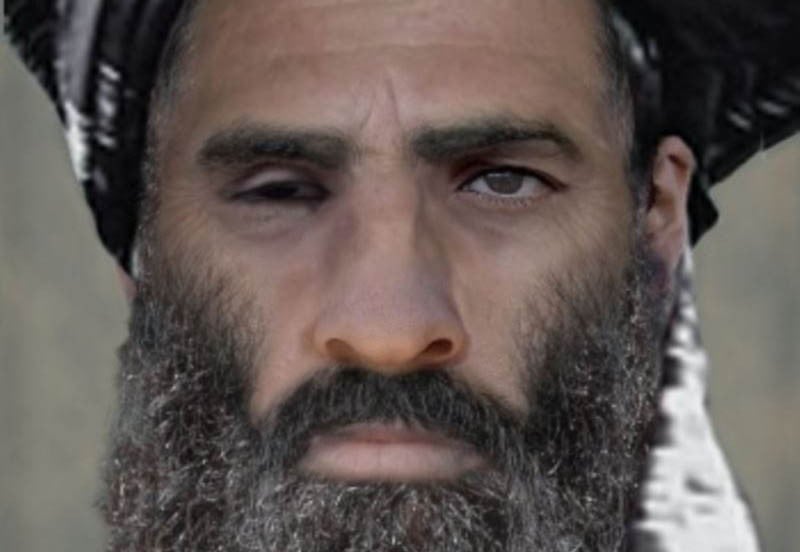

The announcement of Mulla Omar’s death signals the end of an era as the founder of the 21-year old movement is no more and a new man, albeit someone tried and tested, is stepping into his shoes

The secret was finally out even though the Afghan Taliban movement tried until the end to keep the news hidden that their supreme leader Mulla Mohammad Omar had died more than two years ago.

Taliban had continued to deny Omar’s death, but indirect confirmation came when his deputy Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor was chosen as the movement’s new head. The Taliban Rahbari Shura (Leadership Council) in a secret meeting on the evening of July 29 also selected Sirajuddin Haqqani, head of the Haqqani network, and a religious scholar Mulla Haibatullah Akhundzada, as his deputies.

Haqqani’s elevation to the post could cause problems because the Haqqani network has been declared a terrorist organisation worldwide. However, the Haqqani network was represented in the July 7 peace talks in Murree between the Afghan government and the Taliban and apparently no objection was raised by Kabul or even the US diplomat who attended the meeting along with two Chinese diplomats as observers. On their part, both the Americans and the Afghans would be relieved if the Haqqani network, considered by the US as militarily the most powerful Taliban faction, were to disarm and join the political mainstream under the terms of a likely peace agreement with the Taliban movement.

According to sources, the first time Omar’s death was publicly announced was at the gathering in an unannounced place on July 30 in which Mansoor was introduced as the new leader. Fateha was offered for Omar when Mansoor told his audience that he has indeed passed away. The next step was for Mansoor to accept the "baiyat" from Taliban elders, military commanders and ordinary members, accepting him as their new "ameer" (head) and pledging loyalty to him.

This signalled the end of an era as the founder of the 21-year old movement was no more and a new man, albeit someone tried and tested, was stepping into his shoes.

It was obvious Taliban wanted to keep Omar’s death as a closely guarded secret and they managed to do so for exactly two years because they were concerned that such an announcement could demoralise their rank and file, particularly the fighters, at a time when the drawdown of Nato forces from Afghanistan had begun and also possibly lead to a battle of succession.

In the end though, the leakage of the news of Omar’s death triggered differences in the Taliban movement as the anti-Mansoor camp began consultations to challenge his leadership and promote the cause of Omar’s son Yaqoob as the new leader in place of his late father.

Finally on July 30, Taliban formally admitted Omar’s death through their spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid and said he had died on April 23, 2013. He said Omar died due to illness, but didn’t disclose the nature of his illness. It was obvious Taliban had been forced by circumstances to reluctantly concede his death. The statement didn’t say anything about Mansoor’s elevation to the position of the Taliban movement head.

This wasn’t the first time that Omar’s death had been speculated, but the denials by the Taliban movement were less forceful this time and certain Taliban members too were asking difficult questions regarding the absence of any proof of life to establish that he is alive. Never before had the Taliban leadership been under so much pressure to provide evidence to its own rank and file and to the world that Omar isn’t dead.

By now, a few facts have come to the surface, but more are awaited. It seems Omar died in Pakistan and his body was shifted to Afghanistan’s Zabul province and buried at a secret location.

There is still no clarity with regard to the circumstances of his death. However, a controversy was generated in the wake of the recent allegation by the small Taliban splinter group, Fidayee Mahaz, that Omar was assassinated on the orders of Mansoor in his capacity as the de facto head of Taliban movement with the help of his aide Gul Agha. Though Mansoor’s camp rubbished this claim, the situation took a new turn following the reported claim by Mohammad Yaqoob, Omar’s eldest son, that his father was martyred. Yaqoob had joined the Taliban factions opposed to Mansoor and was emerging as a serious contender to become the ameer (head) of the movement in place of his father. However, Mansoor moved quickly to scuttle his chances by managing to seek the support of Taliban shura members to become the new head.

Despite Mansoor’s elevation as the Taliban movement head, he still would have to contend with the factionalism in its ranks and overcome differences that erupted due to the controversy surrounding the circumstances of Omar’s death. Mansoor is resourceful enough to tackle the opposition, though it is obvious he doesn’t have the status and popularity that Omar commanded among the Taliban as the founder of the movement.

Mansoor was obviously the top contender because he was personally picked up by Omar as his deputy and led the Taliban movement for the last many years, including the two-year period when Omar had already died. Yaqoob had emerged as his main challenger due to the unparalleled popularity of his late father among the Taliban and the outpouring of sympathy for his family following Omar’s apparently mysterious death. Yaqoob’s shortcoming was his young age as he is just 26 years old and his lack of fighting and administrative experience.

The name of Mulla Abdul Ghani Biradar, who before Mansoor was the Taliban deputy head and a friend of Omar, was also mentioned as the likely new leader of the movement. It was speculated that he could become a compromise candidate in case the disagreements between the Mansoor and Yaqoob camps aren’t resolved. The fact that he has been in custody of Pakistani authorities for the last several years was a disadvantage because he has been away from the scene for quite long.

The absence of a strong leader like Omar could affect the working of Taliban movement and slow down the Taliban fighters, who launched their annual summer offensive in April and dramatically increased attacks against the residual, 14,000-strong US-led Nato forces and the almost 400,000 Afghan security forces. However, Mansoor ran the show in Omar’s absence for two years and even before that when Omar had to go underground to avoid being killed and captured. Omar was one of the most wanted men in the world as the US had announced $10 million head-money on him.

Omar, a village cleric of humble origins who fought against the Soviet Red Army in the 1980s and then challenged the Nato forces following the US invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, had kept the Taliban movement intact and converted it into a formidable fighting force. In his capacity as the "Amirul Momineen" (Commander of the Faithful) of the Taliban, his followers obeyed his every order and fought in his name. This cannot be said of Mansoor or any other Taliban leader.

Already the change in Taliban leadership has led to postponement of the second round of peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government that was to be held on July 31. As some Taliban leaders said they first want to put their own house in order before talking to Kabul. Also, the talks would involve give-and-take if these are to move forward and Taliban won’t be able to offer concessions to the Afghan government unless Mansoor is able to consolidate his position as Omar’s successor.