Our classical music is basically melody and rhythm. There is no harmony in our music, that is to say, it does not have a combination of simultaneously sounded musical notes. Any harmonic implications you hear are purely incidental. The one vocal -- or instrumental -- compositional form held in common through our subcontinent is the Raga. And a Raga is fixed, unchangeable number of no less than five notes put together to form a musical scale. Each Raga has an ascending and descending structure.

The history of the Raga goes back to more than two thousand five hundred years. The classical music we hear in our country today has acquired its present form after the arrival of Muslims in India. I am over-simplifying musical history only to make the point that "Raga business," as my friend Ibrahim Jalees used to call it, is not nearly as off putting as he thought it was. Any tune, any hit number, any folk song has its roots in a Raga.

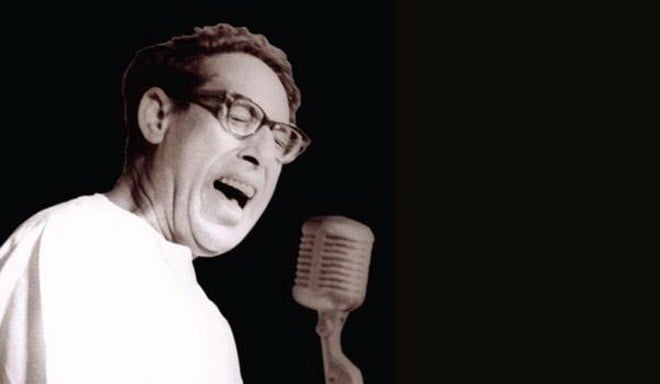

The classical singing in Pakistan today, be it on radio and television or in a live concert, is an exercise in frenetic outpouring. True, the performer begins with an alap (the slow and gradual unfolding of a Raga) but only as a formality. All too soon he seeks the sustenance of the percussionist. It is conceivable that on television he is rushed for time, but even in a live concert where a classical vocalist sometimes sings for well over an hour, he is more interested in showing off his pyrotechnical ability, which is lamentable.

Our music is mostly vocal and the ‘solo’ nature of all our musical contemplation gives it an esoteric flavour. Instrumental technique has been largely directed to produce vocal effects. When a great sitar maestro like Vilayat Khan who has mastered the art of gayaki ang plays, his instrument talks not in the manner in which a cello produces the composer’s note but as though it is uttering the words of a lyric.

Instrumental or vocal, our music should always have, in the background, the so-called drone known as the Tanpura. It is difficult to describe the true place of this instrument in terms of Western (Classical) musical experience. On the face of it, it produces nothing more than an elongated Ummm… Its sound is continuous and unchanging from the beginning of the performance to the end. The Raga which is being sung against the Tanpura makes it notable as an ambience. Musical forms leap out, live transfigured for an instant and are quenched.

Time was when our classical musicians used to take great pride in their Tanpuras. The fact that they don’t, any more, speaks volumes for their lack of sensibility. It is sometimes seen in the background held by an indifferent minion, but its purpose seems to be more ornamental rather than to be an accompanying instrument. (On television you see two such minions holding the tanpura, but the sound recordist, or perhaps the producer, makes sure that its sound is never heard).

The great performers of the past exercised the utmost care in selecting a Tanpura for their use and tuning it with incredible skill and precision. Singers like Srimati Bai Narwekar, Fayyaz Khan, Kesar Bai, Amir Khan et al, drew from this undifferentiated ocean of sound the little cornices and casements and the fretted architecture of their art. More: from the Tanpura they obtained the assurance and the faith that they were truly connected with the source of their musical illumination. It was in the swirling sound of the Tanpura on the crest of which they were perched that they travelled through the complex rigmarole of rhythmic patterns with logic and inevitability which was sometimes astonishing to behold.

I often regret that our classical musicians do not pay enough attention to silence during a performance. Depending upon the nature of a Raga, a performance may have many moments of prescient silence. The stillness in a highly receptive state of mind is sometimes more evocative than the parts that sounds play.

Listen carefully to Ragas like Abhogi Kanra and Sree performed by that great maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. The stillness is sublime as it hovers over the alap; it lurks about the nooks and corners of the Raga, always eminent, just behind the quivering grandeur of Abhogi or the dying fall of Sree.

There is a peculiar notion in our country that the greatness of a vocalist is to be gauged by the length of his performance. Even discerning listeners when describing a concert say, "Ustad Haider Baksh outsang everyone else, he sang Raga Poorya Kalyan for two and half hours."

Length has nothing to do with our classical music. It is, if anything, a social custom like marriages. The ritual of marriage in Karachi or Lahore takes days to conclude while a Latvian or a Swiss is married in half an hour. Both, the Latvian or the Pakistani live long and happy -- or unhappy -- married life according to their lights.

The musical experience is a timeless experience; its timelessness is its chief contribution. How long a classical singer sings for depends upon his attitude toward his art. If pre-occupied mainly with the form of his art rather than its content, he could take several hours, but this would be very much like the guide describing the history of every stone in a monument so that the tourist does not see the monument but is filled with its chronicle from basement to turret. A twenty minute recital of Raag Marwa by Amir Khan Indorewalay can be so intensely moving that one is transported into the realm of beyond.

The creativity of an imaginative and sensitive musician comes to the fore when he is able to evoke a sense of yearning among his listeners. His improvised meandering transcends them. They go into ecstasy as they experience an inexplicable sense of pathos. Let us not forget that suffering and its interpretations have been one of the keynotes of Eastern contribution to human experience.

Our sublime musician sits cross-legged with only a Tanpura holding him up while a Sarangi follows his voice and a percussionist waits for his nod. The sublime musician cannot go back to correct what he has sang for even as he sings, he is, at once, the composer and the performer. He cannot rub out a trill or put in a staccato (as Beethoven and Brahms could). He has to live from moment to moment, here and now, with no pages of score before him. Thus it is that he creates the illusion that his entire performance is extemporised.