The State Bank of Pakistan’s interest rate cut is considered essential for economic growth, which would eventually benefit everyone, including the small savers. But, this has not happened so far

The State Bank of Pakistan’s interest rate cut of May 2015 was a significant achievement for Finance Minister Ishaq Dar and his team at the ministry. The new, seven per cent rate was not only pitched as a significant improvement over the previous eight per cent, it was also a step closer to the IMF-mandated 6.5 per cent. But lost somewhere in the din over newspaper headlines -- 42-year low! Lowest ever! Business-friendly! -- seems to be an understanding of what the rate cuts are doing for the economy.

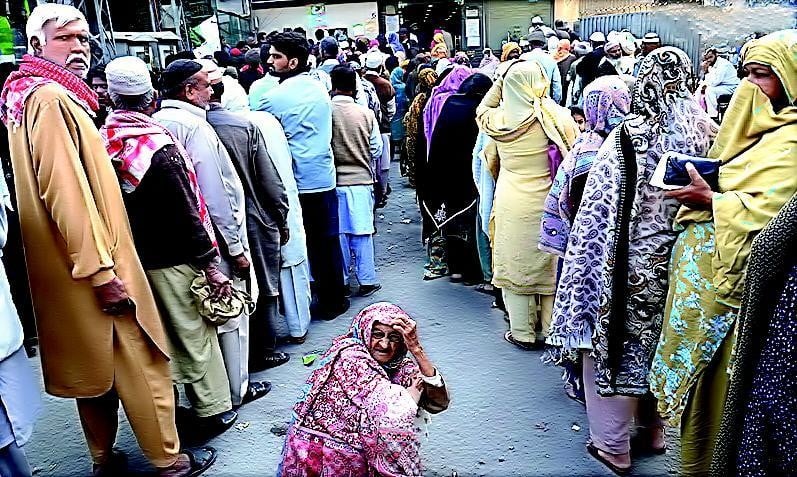

From the high of 14 per cent in November 2010, interest rates in Pakistan have been waning steadily. Be it the PPP or the PML-N, every government has ceremoniously celebrated each cut. Those who complained about the hit taken by small savers -- widows, pensioners and others who relied on income from investment to bolster their salaries -- were ponderously told that the cuts were essential for economic growth, which would eventually benefit everyone, including the small savers.

This has not happened so far.

From November 2010, the key policy rate has fallen by seven per cent or 700 basis points. But official figures show that GDP growth (with 2005-06 as the base) has gone up from 2.58 per cent in FY 2009-10 to just 4.25 per cent in FY 2014-15. This is clearly not the stuff Asian Tigers are made of.

The last two financial years offer an even more startling indication of how this growth-interest rates trend has shaped up. In June 2013, the discount rate was cut from 9.5 per cent to nine per cent but inched its way up to 10 per cent over the course of the financial year. Growth was a moribund 4.03 per cent and credit to the private sector during this period was 378.9 billion rupees. But the discount rate lost another 300 basis points from July 2014 to date. And the impact on growth? Just 4.24 per cent while credit to the private sector has slumped to 163.8 billion rupees.

Clearly, the cuts alone are not doing it for the business community.

Realistically speaking, how could they? Traditionally, big business hunkers down in an election year because they’re waiting for the new government to settle in. And the Nawaz government was too busy battling militancy, the riotous PTI and a resurgent military establishment to be of much use to the business community. Even those who may have been enthusiastic about investment and job creation had the drive beaten out of them by the roiling blackouts and the run on the rupee.

And so the elephant in the room remained unseen for another two years.

The problem with using interest rates to woo businesses and investors is that it presumes a causality that does not exist in Pakistan at present. The theory that lower interest rates will inspire businesses to invest works when first, other circumstances are propitious and second, banks want to lend to businesses and corporations. For too many years now, banks have focused primarily on the one client whose credit standing is gold and who offers competitive returns on investment: the government of Pakistan.

On the face of it, the PML-N government seems to be tightening its belt: from a fiscal deficit of 8.2 per cent of GDP in FY2013 under the PPP government, the size of the deficit went down to 5.5 per cent in FY 2014, five per cent in FY 2015 and is targeted to come in at under five per cent during the ongoing fiscal.

But the government borrowing numbers are far less austere. During fiscal year 2014, the federal government borrowed Rs169 billion from the scheduled banks alone while total government borrowing clocked in at Rs374 billion. In fiscal year 2015, however, the federal government borrowed Rs 1.3 trillion from the scheduled banks, with the total size of government borrowing coming in at a stunning Rs1.1 trillion.

With a seemingly insatiable appetite -- government borrowing from banks has increased by approximately 640 per cent in just one year -- is it any wonder that the government of Pakistan is the preferred client of banks all across the country? Or that these banks prefer low-risk, secured return government paper to pesky and problematic investors in a highly insecure business climate?

And this is the elephant no one wants to acknowledge.

To be fair, the government’s addiction to living beyond its means is neither new nor peculiar to the PML-N. As the latest Economic Survey intones ponderously, the 8.2 per cent fiscal deficit of FY 2014 owed to "delays in implementation of tax reforms and expenditure overrun due to loss making PSEs, security related expenditures, untargeted subsidies and higher interest payments. Due to persistently high fiscal deficits, endeavours to achieve fiscal policy objectives such as sustained economic growth along with declining debt services, alleviating poverty and investing in physical and human infrastructure were severely hampered in the past owing to absence of enough fiscal space to cover the rising public expenditures." Except this is the problem every finance minister runs into.

Theoretically, government paper -- the treasury bills mopped up by the commercial banks but especially the National Savings Schemes (NSS) so beloved of the small savers -- should carry the lowest returns: where the borrower is the sovereign of the land and can print currency at will, the risk of default is negligible. But current rates on NSS instruments vary between seven per cent and 10 per cent while the minimum rate on bank savings is four per cent. While the social security aspect is a worthwhile argument -- pensioners and widows should have financial security -- their needs should not be used as a fig leaf for the government’s inability to live within its means.

By leveraging its position as sovereign, the government is essentially crowding out banks and other financial intermediaries in deposit mobilisation and other prospective borrowers in bank borrowing. Why would a saver put their money in a bank when an NSS instrument offers a higher return? To compete with the GoP in mobilising deposits, the banks would need to offer higher rates of return, lend at even higher rates. And to repay bank loans carrying such exorbitant rates, prospective clients would need to engage in far riskier businesses that would yield the highest returns. Is it any surprise that banks are choosing the government over all other borrowers? Or that policy rate cuts are not translating into economic growth?

The true cost of this flawed intervention strategy is borne by the financial system but these effects will manifest themselves only when businesses resume interest in investment and expansion. Already, in line with global trends, many corporations have turned to bonds and other such instruments to finance their plans. As this retail bonds market grows, it will obviously eat into the profitability and the prospects of the banks, which will be forced to redefine the financial intermediation business as they’ve known it so far.

Till then, the banks and the government will continue with the pretence that policy rates affect growth. As for the small savers? They already know the NSS is the best game in town.