With very few training institutes around, new theatre groups are filling the gap for young enthusiasts -- not without their set of problems

‘Revival’ is a buzzword these days. It’s mostly thrown in at a mention of our local film industry. But theatre in Lahore, it seems, is also at a point where it is experiencing a sort of a revival.

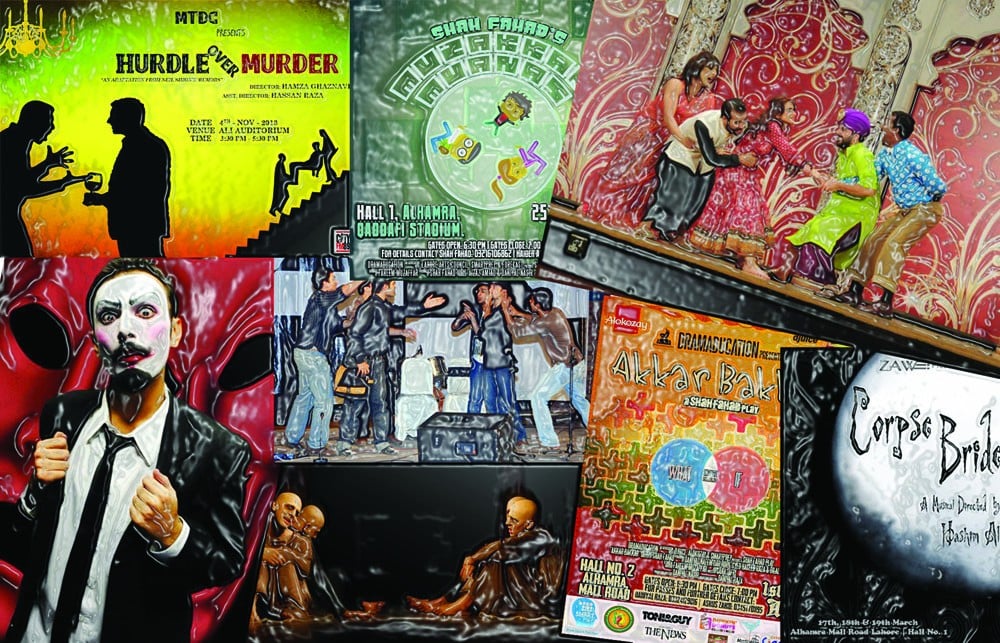

Over the past few years, a lot of people -- mostly young, 20-something -- with a passion for theatre, have become associated with the field, be it as actors or props managers or prompters or directors. A number of theatre groups have sprung up, though most of these do not boast so much as even an office space -- they, usually a bunch of likeminded friends, gather at each other’s place and discuss projects in creative all-nighters.

Consider Dramaducation, for instance -- a private theatre production house, started in 2011 by Shah Fahad, a FAST graduate who is best known for his various comic avatars in the many plays that he has directed and acted in. "Earlier, we would decide on a meeting place and rehearsals venue," he tells TNS. "It would usually be STEP Institute of Design. Today, we do most of our pre-production work and rehearsals at Olomopolo, our regular partners.

"We are hoping to get our own space by next year," he declares.

Under his banner, Fahad not only produces plays but also trains aspiring actors. "For example, we get LGS students who can think of no other hands-on training place in the city. Yes, there are institutes such as BNU which teach Theatre Studies but if you want to learn it independently, there aren’t many venues."

Fahad works with "a regular team of 30-35 people… four directors and writers. The backstage crew is also permanent."

But he insists that "putting together a play is no mean feat. Period.

"Personal funding can be exhausting."

Another well recognised stage actor, Faheem Muzaffar seconds Fahad but adds that there is something addictive about theatre, "Call it fascination or whatever, but it keeps most of us young, independent theatre actors going.

"What is more fascinating than performing before a live audience? It gives you an adrenaline rush," he says.

Both Fahad and Muzaffar agree that theatre is one of the most difficult of performing arts. "Unfortunately, theatre in Lahore has come to be associated with the cheap Punjabi stage shows that are performed after 10pm at the same venues," says Shah Fahad. "They are packaged in vulgar dances and crude humour. But trust me, the city has seen some quality plays in the recent past, especially those produced by new comers. These weren’t big productions, so getting financial support or sponsors was very difficult."

Muzaffar believes "an amateur production or not, we have to always rely on sponsorships and ticket sales. The problem is that hardly anyone wants to watch a ticketed play in Lahore. Sponsors we manage to get, though. Eventually, we reach a break-even point. There are rarely any profits to reap. All we gain is contentment."

"Considering Lahore’s rich cultural and literary history, it is sad to see that theatre is not growing as much as it should have," says Hamza Ghaznavi, a theatre actor and director, who recently graduated from Lahore School of Economics (LSE). There is an obvious sense of disappointment in his words.

He believes "established groups such as Ajoka are not the only answer, as they usually cater to niche audiences. They produce plays on hard-hitting socio-political issues. Most of these are repeated year after year, but with different set of actors and crew. This does mean budding artists have an opportunity but such groups or institutions are only few and far between; they cannot accommodate a large number of theatre enthusiasts out there."

Ghaznavi also pinpoints the need "to explore different genres that would appeal to larger audiences."

In reply to a query, he says, "Lahore lacks proper infrastructure needed to host plays. Other than Alhamra Arts Council, there are no many suitable venues where the activity could be carried out."

"Most halls are a technical and aesthetic disaster," adds Muzaffar.

All these people agree on the fact that the major issue is one of commercial viability of theatre. As Ghaznavi puts it, "Karachi has an audience for theatre that doesn’t mind ticketed plays. Lahore’s case is quite the contrary.

"It’s only when the Karachi groups come to Lahore for performances that we see full houses despite the ticket prices being as high as Rs1500-2500. Check out Nida Butt [of Mama Mia fame] or Dawar Mahmood [actor-director of such hugely successful plays as Pawney 14 August].

"The ticketing culture needs to be cultivated in Lahore," he insists.

Hamza Ghaznavi also laments the fact that Shah Sharabeel was Lahore’s answer to Karachi’s Nida Butt but he has now shifted base. "This is quite discouraging for new comers."

According to Muzaffar, "When you are starting, the charm of the art is motivation enough. But overtime, you need money to put a project together. The financial crisis can stifle your passion."

For Shah Fahad, "Commercial success matters also because it means you can come back and start another project. Big names bring with them big sponsors and also help you to market your play better."

There are groups such as LAAL whose declared focus is on "using artistic media to spread ideas for a progressive Pakistan," (words of Younas Chaudhry, an important part of the group).

"However, the need for entertaining plays runs parallel to the need for ‘responsible’ theatre."