The world of some great artists imagined by one of the most original fiction writers of our times

Writers and visual artists are often considered distinct from each other, even though there have been constant connections between the two at various levels. Some artists are known for their works of literature while some writers have also expressed through the medium of visual arts. A few are equally proficient in both realms such as William Blake, Gao Xingjian or Ram Kumar, to name a few.

There have been other bridges between the two modes of creative expression as several authors have extensively and regularly written on visual arts. Compared to the works of trained (or untrained but ambitious) critics, the texts of literary authors on art offer a refreshing view and new version of things -- mainly because they are able to infuse an unusual aspect into writing on art. Therefore, their writings offer an exciting approach and extraordinary insight along with the pleasure of reading.

Many writers have engaged in writing on art, with Baudelaire being the most prominent from the age of Modernism, and several others including Apollinaire, Andre Malraux, Octavio Paz, John Updike, Yves Bonnefoy and Roberto Calasso. A recent book published on May 7, 2015 by Julian Barnes adds him to the list of the illustrious authors who have shifted their discipline and focused on a separate art form. Keeping An Eye Open is the collection of his essays on artists written from 1989 to 2006, initially for various publications, like Modern Painters, Guardian, London Review of Books and Times Literary Supplement. The first chapter of the book (on Gericault) is from Barnes’s novel ‘A History of World in 10 1/2 Chapters’. The last one was for ‘Hodgkin: Writers on Howard Hodgkin’ published by Irish Museum of Museum of Modern Art. But all of these seem relevant and valid when read in a sequence.

One presumes that a man of letter like Barnes, twice winner of Man Booker Prize and known for his novels and short fiction, would have attempted writing on artists from an outsider’s position. Surprisingly, his commentary and analysis are thorough and reflect a deep understanding of the issues and concerns of pictorial practices; almost a professional’s approach.

In some pieces he talks about artists and their contemporaries, especially the relationship between Manet and Zola, and how the work of one influenced and inspired the creativity of other. While writing on Manet, he observes: "His most famous ‘literary’ painting -- of Zola’s Nana -- is not at all what it seems. He portrayed the courtesan when she was still only a minor figure in the serialisation of Zola’s earlier novel L’Assommoir. Huysmans, in a review of the picture, announced that Zola was going to devote a whole novel to Nana, and congratulated Manet on having ‘shown her as she undoubtedly will be’. So you could say it was Zola who ‘illustrated’ Manet, rather than vice versa."

This passage signifies how the interaction between the two disciplines was a normal occurrence in Paris of Modern Age. In his essay ‘Delacroix: How Romantic?’ Barnes discusses in detail the journals of French painter who "was twenty-four when he began the Journal on 3rd September 1822. It opens with a simple declaration and an alluring promise:

‘I am carrying out my plans, so often formulated, of keeping a journal. What I most keenly wish is not to forget that I am writing for myself alone. Thus I shall always tell the truth. I hope, and thus I shall improve myself’."

Barnes comments "You can see why some believe that all private journals are at some level intended to be read by others."

This aspect is not peculiar to the text of Delacroix: one recalls the example of Franz Kafka who asked his friend Max Brod to destroy his manuscripts and diaries after his death but perhaps knew that his closest friend won’t respect his last wish. Hence, one is aware or conscious of the audience in whatever one writes.

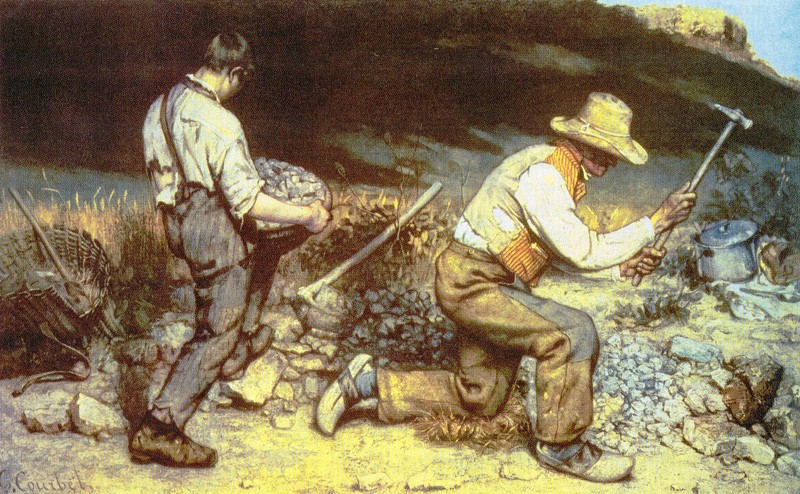

This is the case with artists too: many painters throughout history have been keen on showing, or rather showing off, their work to the viewers. An apt example is that of Gustave Courbet. Barnes mentions that Courbet "created, or adapted to his use, the persona of the boisterous, belligerent, subversive, shit-kicking provincial; then, like some contemporary TV personality, he found that this public image had become indistinguishable from his true nature. Courbet was a great painter, but also a serious publicity act. He was a pioneer of self-marketing".

One can identify several artists of our times who are following the example of Courbet -- by recording their selfies constantly and posting these and other activities non-stop on the social media. However, Courbet’s life was full of unexpected events and upheavals: "If French state didn’t crucify Courbet, it certainly did its best to break him: his property was requisitioned, his pictures were stolen, his assets sold, his family spied upon." He left Paris for Switzerland "but renewed turmoil in France kept him an exile until his death that December" (1877).

Not only Gustave Courbet but other artists too are represented as ordinary mortals rather than larger-than-life characters. For instance, Edgar Degas and other artists are shown as men of many contradictions, particularly while quoting comments of their contemporaries and competitors.

But, apart from this, what impresses the reader is the sheer insight of the author in the mechanics of visual arts. In his essay ‘Manet: In Black and White’, Barnes discusses the making of three versions of The Execution of Maximilian by Manat. He writes in depth about the painter’s method of constructing an event that was reported without providing any photographic documentation in the beginning. He also elaborates on the painter’s preference for using multiple shades of black, and how the painter employs minimal means to attain maximum impact.

Moving away from the periods of Realism, Impressionism and Post Impressionism, Barnes has commented on subsequent artists such as Rene Magritte, Claes Oldenburg, Lucian Freud and Howard Hodgkin. But his approach is different from the author of Madame Bovary as: "Flaubert once said, in reply to a journalistic enquiry about his life, ‘I have no biography’. The art is everything; its creator nothing." Barnes, on the other hand, blends biography with analyses of art in order to formulate remarkable portraits of the makers of works of visual arts. He reflects: "How long do we spend with a good painting? Ten seconds, thirty? Two whole minutes?" However what is created by Julian Barnes in Keeping An Eye Open does demand a longer time -- not just for reading these pages but to live in the world of those real beings imagined by one of the most original fiction writers of our times.

(The book is available at Readings Lahore)