In a recent group show at Alhamra Art gallery Lahore, a number of artists took a remarkable position of deviating from representational visuals

In 1899, while posing for Paul Cezanne, the Paris art dealer Ambroise Vollard dozed off. The painter was angry: "Wretch! You’ve ruined the pose! I tell you in all seriousness you must hold it like an apple. Does an apple move?" Not only apples, but other objects, plants and human beings never stirred in the canvases of Cezanne, one of the greatest exponents of modern art.

Now after more then a century, things of all kinds are moving in all directions, as was seen in a recent exhibition (May28-June 6, 2015) at Alhamra Art Gallery Lahore. Here, a tree was uprooted and suspended inside the gallery space. Barren with no leaves, the brown branches, trunk and roots were a few inches above the ground. Normally when we look at a plant (unless it is a stem in a beautiful bottle) we always connect it with gravity as well as its link to the soil. However, the work titled ‘Unanchored’ by Sarwat Rana, more than defying these notions and associations in a clear or direct manner, delved in a space that lied in-between reality and artistic intervention. The scale of the piece, the choice of using a found object, and the selection of an existing tree that, ironically, appeared more like the idea or archetype of tree were a few characteristics that made Rana’s work unusual and extraordinary.

The particular piece of sculpture was part of Built In, a group show curated by Aamna Hussain. Based upon the concept of geometry, the exhibition consisted of works by artists who have not shown extensively, yet their works offered their pictorial quests and development as serious professionals. The curator shared her theme -- of finding hidden geometry in art -- and her preference for artists who are employing elementary shapes and basic forms to construct their imagery. The display included sculptures, installations, mixed media works on paper and paintings.

An important aspect of this show, besides the curator’s careful and clever selection of artists and exhibits, was to realise how a number of artists have been deviating from a recognisable and readable pictorial vocabulary. In a society that is too concerned about meaning, story and content, the act of shifting from representational visuals is a remarkable position. The culture’s craving for identifying and comprehending everything is so strong that each word in our languages must mean something.

For many viewers, a work of art that does not show or suggest a human figure, elements of nature, identifiable items and readable script is meaningless. The concept of abstract art being paired with the West, in comparison to representational imagery that is believed to be local and indigenous, has some basis if we forget the long past of Muslim, Hindu and other non-European civilisations, and believe in ‘abstract art’ to be an evolved phase of Western art history.

In many cultures, existing outside the mainstream European art, non-representational art forms were practiced to the level of perfection. Geometry or sacred shapes were the source to draw visuals which do not have apparent meanings but have latent content and codes. Examples can be found in the objects produced in Muslim architecture, Hindu and Jain paintings, Turkish and Persian miniatures and Japanese aesthetics among others.

So a work that had geometric forms held a complexity of interpretations. But today an artist who belongs to the tradition of Non-European aesthetics, yet is trained in Western art history and practice, blends the two and creates works that allude to multiple sources and ideas. At the exhibition, Built In, this approach was visible, especially in the works by Mina Arham, Minahil Hafeez , Sadia Farooq, Manisha Jiani, Ghulam Hussain, Abbas Ali, Sajid Ali Talpur and Moattar Zafar. Mina employed a basic technique to create connecting, continuous and panoramic views of urban constructions in black and white. The simplification of rendering and the selectiveness of vision added a layer of subtlety in these otherwise urban landscapes.

Identical approach toward geometry was visible in the works by Minahil Hafeez, Sajid Ali Talpur and Manisha Jiani. The former two added small marks to compose basic shapes which, like music, had an impact of depth on the spectators, while Jiani overlapped rectangles of various greys on a canvas which signified the memory of absent canvases. Her work consisted of marks of edges of paintings, as if put on a wall for too long, conveying her concept about the phenomena of exhibiting art, gallery business and marketing.

Two other works indicated artists’ desire to experiment and explore their formal concerns. Both of these, the paper weave by Ghulam Hussain and triangular marbles by Sadia Farooque, were displayed on the floor, thus offering more of a visual experience rather than a ‘finished’ product.

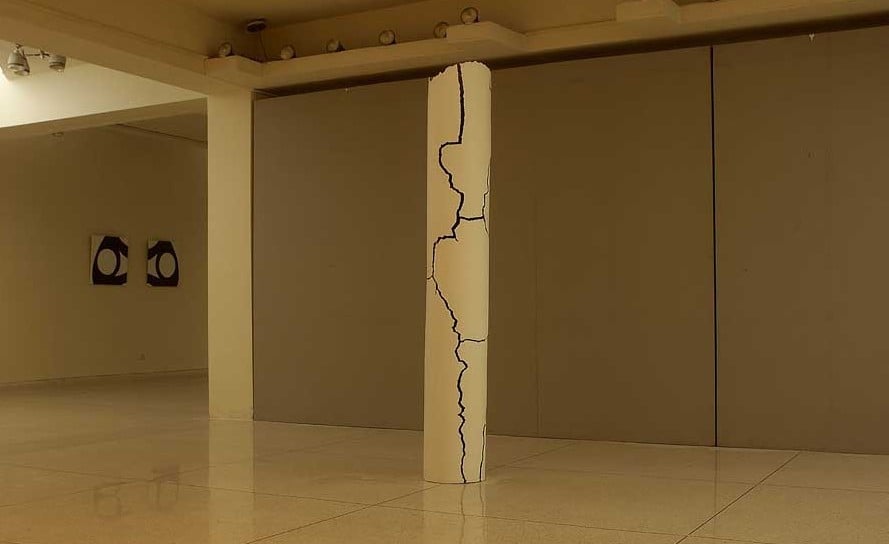

The openness in the two works, especially of Farooque, which could be arranged in any order, coincided with another sculpture (Endless Knots) by Sarwat Rana. She picked a flexible industrial pipe and turned it in such a way that the mass on the floor suggested an organic form. Along with material and scale, the process of making this piece was interesting. The importance of process was evident in the work of Umer Nawaz, too, perhaps the most exciting entry in the show as he had built a column with creaks. One presumed that due to fragmented portions, the column would fall on the floor, but these apparently disjointed parts were contained within the outline of the column due to a concealed support structure. An exercise in contradiction, the work could be read in any way depending on a spectator’s political position or social opinion. Some may interpret it as a symbol of society falling apart, and others could view it being a sign of strength and integrity.

In both cases, the pictorial pleasure or contrast between impossibility and probability was the real content of the sculpture, as in works by other artists who used geometry as their point of departure and source of inspiration. These artists can learn from Cezanne who concentrated on objects which were static, like apple. Yet his work moves millions when they are in front of his portrait of Vollard or his still lifes laden with apples.