In the aftermath of attacks in Karachi, the dominant mood across the country is to go after the militants instead of forgiving and co-opting or holding peace talks with them

All it took was one more major terrorist attack to change the upbeat mood in the country to despondency.

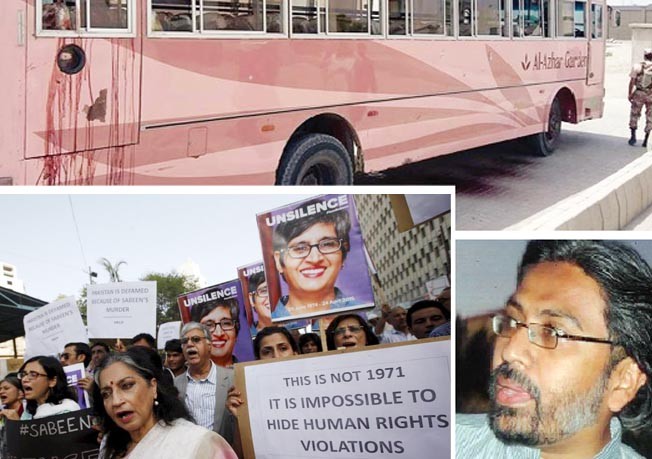

Until the May 13 incident in which 46 innocent members of the Ismaili community were mercilessly shot dead in their bus in broad daylight in Karachi’s Safoora Chowrangi, there was growing hope that the security situation was getting better. It was widely believed that the decrease in the number of bomb blasts and suicide bombings during the last year was due to the diminishing strength of the militants.

The statistics backed up the feel-good sentiment that the militants were facing defeat and the scourge of terrorism was on the wane. However, the situation changed following the latest terrorist strike to hit the seemingly ungovernable mega city of Karachi. There are again misgivings whether the terrorists could be decisively defeated in the near future so that Pakistan could move on and become a peaceful and prosperous country. Until then, the aspirations of its long suffering citizens are unlikely to be materialised.

Such a situation has arisen in the past also, but the feeling of helplessness was stronger this time as the new terrorist attack took place when the nation was given to believe that the ongoing military operations in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), particularly the ‘Zarb-e-Azb’ that was launched in North Waziristan on June 15, 2014 and the ‘Khyber-1’ and ‘Khyber-2’ undertaken last winter in the Khyber Agency had broken the back of the militants. In Karachi, the Rangers-cum-Police action had justifiably raised hopes that Pakistan’s biggest and richest city was on the way to normalcy after suffering for years due to ethnic and sectarian violence, acts of terrorism and organised crime perpetrated by target killers and drug mafias.

However, one may continue to remain hopeful that the journey toward peace and tranquility has been disrupted rather than being halted.

There are reasons to be hopeful. The arrest of the four educated young men on the charges of involvement in a number of terrorist attacks, including the one on the Shia Ismailis within a week of the incident, came as a pleasant surprise. Many felt pride in the performance of the police investigators even if there was an element of disbelief that a small cell of 15-16 members with the four detained men forming its core was capable of carrying out such complex and horrendous attacks and killing so many people.

Questions were also asked if this cell was indeed operating independently as claimed by the Sindh government and its police with no links to the known terrorist groups.

It isn’t clear if some of these questions would be answered once the trial of the arrested four men is undertaken.

Pakistan Army Chief General Raheel Sharif was referring to the kind of urban terrorism that manifested itself when the Ismailis were targeted and has ravaged Karachi for years when he told the under-training officers recently at the Command and Staff College, Quetta that the Operation Zarb-e-Azb had created space for a decisive action against terrorists in urban areas, and it is time "for political optimisation towards a meaningful and sustainable closure". He also made it clear that armies alone cannot fight wars as the nation has to put in efforts to tackle the complex, multi-dimensional and hybrid threats confronting the country.

General Raheel Sharif, who is leading from the front in the war against terrorism and has been able to push Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s government into action, opined that the ongoing surge in terrorist attacks needed something more than conventional retaliation.

The Army chief’s views appeared to be an effort to remind not only his officers but also the ruling political elite and the nation at large that the war against terrorism could be long and that it needed to be fought by whatever means necessary. Such reminders are necessary to keep attention focused on the job at hand as the political governments tend to do too many things at a time without really completing anyone. It is obvious the General wants the politicians and all other segments of the politicians to share the ownership of this difficult and costly war because the heartbreaks and hurdles on the way could dilute the nation’s commitment to continue fighting it.

Though there is no appetite right now for again holding peace talks with the militants, some well-meaning people are asking if certain militant groups could be neutralised by engaging them in a dialogue and pulling them away from the hardcore elements in a bid to divide and weaken them.

However, no politician or analyst is demanding peace talks because it is politically risky at a time when the public has almost completely turned against the militants and is seeking tougher action against them. The failure of earlier efforts at peacemaking has led to lack of interest in any more peace talks with the militants. Also, the militants have sent a strong message that they prefer the use of force by carrying out some of the most horrendous terrorist attacks in the recent past such as the one on the Army Public School Peshawar in which 153 persons including 135 school children were killed and then the brutal killing of 46 Ismaili bus passengers in Karachi.

Still the security officials managed to lure a noted militant commander, Haleem Khan in North Waziristan in a bid to cause a split in the group led by Hafiz Gul Bahadur. Many tribesmen wondered why a hardline militant commander had again been forgiven and co-opted after Operation Zarb-e-Azb. This created doubts about the government’s future plans in North Waziristan where the tribal people are under-pressure from the authorities to decisively throw in their lot with the state and abandon any thoughts of the return of the Taliban militants.

The dominant mood across the country right now is to go after the militants instead of forgiving and co-opting or holding peace talks with them. Anyone calling for peace dialogue with the militants would face the harshest criticism. One doesn’t know at this stage when such a proposal would find some support, but this is unlikely to happen anytime soon.