For creation of a rational thinking environment to counter militancy, intellectuals and educationists need to start a serious debate on Pakistani history, culture and present social structure

The Peshawar tragedy of December 16 will be remembered as an incident which quietly influenced our political and social behaviour. The gory attack on a school developed consensus among political leadership, civil and military bureaucracy, intelligentsia and general public; for an iron hand approach against militants.

While there was popular support for a hardline approach, a debate also started about the appropriate strategy to deal with militancy. The people who desired tough actions without placement of any limits; and the cautious intellectuals, lawyers and members of civil society who wanted to keep in consideration the constitutional limits, both seemed to agree on this point that long term concrete steps are required to fight the menace of militancy and terrorism. Even supporters of instant and harsh actions didn’t deny the need of long term measures, but they had different priority lists.

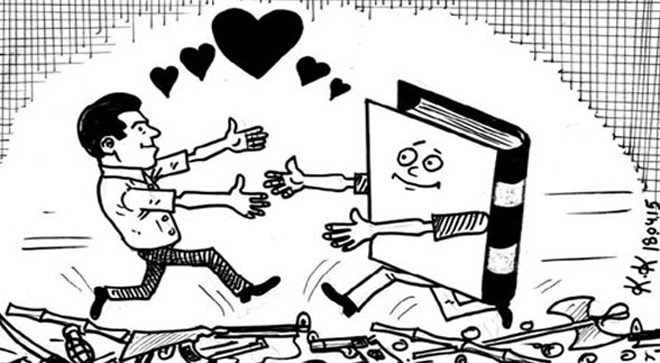

During the period when the strategy to fight militancy was debated in media, there was much talk about adoption of a new narrative. But at that time and even thereafter, no one talked about ‘contents and style’ of new narrative. Nevertheless, it could be safely presumed that the intention between the lines was to create a cultural and intellectual environment where logical reasoning, discussions, persuasion and ability to understand others point of view, is developed at least in educational institutions.

The desire may be highly commendable but the fact cannot be ignored that the new intellectual and behaviour environment cannot be created in days, months or even in few years. This requires a vision, long-term planning, general consensus among decision makers and contributors to draw a strategy and take certain decisions. But before adoption of a strategy or even thinking about it, prevailing situation needs a sound analysis.

The prevalent milieu has roots in traditions, customs and culture developed over a long period. To erase the imprints of ideas, thinking and intellectual systems require more time than consumed in the process of building the existing intellectual structure.

For creation of a rational thinking environment, intellectuals and educationists mostly talk about the changes in the curriculum. Whereas, the curriculum only lay down broad parameters under which students’ learning outcomes are assessed. Textbooks, teaching methods, open debate environment in and outside the class play crucial role in development of youth’s learning behaviour and mindset. The contents of textbooks and its presentation have quite an impact upon students’ imagination, and mould his or her thinking and approach towards family, society and nation.

Textbooks production in Pakistan needs more detailed discussion. At the moment here we will only touch the curriculum.

For decades everyone is talking about changes in curriculum. Different people have different reasons for bringing in changes in the curriculum and textbooks. Some believe that the textbooks are centered around hate material which is not in conformity with the needs of modern world which is moving toward the goal of non-violence and free from every kind of prejudices including based on religion, race and nationality. Others argue that textbooks and syllabus covers such periods of history and personalities who don’t have roots in the soil of this country. They object to the non-inclusion of local heroes and sons of soil in textbooks, belonging to certain races, colour and religions who fought against the imperialist forces.

Political activists who believe that textbooks should openly support the ideas of democracy and human rights and educate children about the negative role of dictatorship in Pakistan’s history. They claim that all ills of today’s Pakistani society are byproducts of dictators’ policy particularly adopted during the period of Zia. Hence, there may not be any such reference which eulogises the role and policies of dictators.

Then there is also a group which is still not satisfied with the measures taken to Islamise the curriculum and textbooks. They demand exclusion of material and content which they consider as secular. Many of them demand that Arabic language be the medium of teaching.

How the foundation of present curriculum was laid down? To understand curriculum in vogue in primary, secondary and higher education, (particularly for history) it is necessary to have a look at the conditions, circumstances under which the existing approach towards Pakistani history, personalities and culture was developed. People may criticise the approach but this is a fact that this was adopted as a result of consensus among the intellectuals and educationists of the time, though opponents were left out grumbling.

The first of its kind of consensus was developed after independence when two educational conferences were held in November 1947 and December 1951. In the first conference in the opening speech Fazalur Rehman, minister for interior, information and education, stated that education should be based on the Islamic conception of universal principles of man, social democracy and social justice. He also dispelled the impression that Pakistan being an Islamic state, will be a theocratic state. He said this perception is "being sedulously fostered in certain quarters with the sole object of discrediting it (the new state) in the eyes of the world". He explained that "Islam has enjoined the granting of full freedom of conscience, security for life and property and opportunity of development to all non-Muslims who are members of the body-politic."

The speech of minister for education is important because it was made part of proceedings of conference and may be viewed as a policy statement.

One of the committee of first conference recommended that religious instructions should be compulsory for Muslim students in schools but the same facility be provided for other communities in respect of their religions. The conference also resolved that the provincial and state governments be asked to take steps to bring the Madrassahs in line with the existing system of general education.

But, the second educational conference held in December 1951 resolved that education cannot exist in a vacuum and that "it must be an instrument of the kind of ideological transformation which Pakistan must stand for". The conference for the first time demanded separate educational institutions for male and female.

The major factor was passing of "Objective Resolution" which was mentioned in the second conference’s resolution as a source of inspiration.

Besides the changes in political and social conditions some personalities also played important role in development of the narrative. Leading figure among them was Dr Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi. He was admired by his students (one of his prominent student was Ziaul Haq) and any criticism on his views for a long time was considered as heretic. Coincidentally, he was also first deputy minister of education and then full minister from 1949 to 1954. He was also member of committee which drafted Qarardad Maqasad (Objective Resolution). Today what we talk about the ‘Two-Nation Theory’ is an idea which was ‘scholarly developed’ by Dr Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi.

Dr Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi (I.H. Qureshi) wrote many books on history of Pakistan. In his book ‘Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan’ he traced the history of Muslims in India from early days and found continuity in the events from the perspective of a struggle of Indian Muslims to keep a separate identity. He stressed that Muslims were a separate nation and movement of heterodoxy in sub-continent was a negative trend in Indian Muslims. Based on this thesis, he identified a line of leaders and intellectuals who struggled to save Mulsims’ identity. He connected Allama Iqbal and Mohammad Ali Jinnah to this stream starting from Mujadad Alf Thani (Sani), Sheikh Ahmed Sarhindi, Aurangzeb, Shah Waliullah, Syed Ahmed Dehlvi, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Johar Brothers (Khilafat leaders).

The thesis of Dr Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi about Muslim history influenced the intellectuals, educationists and establishment. It therefore got space in textbooks of History and Pakistan Studies. The alternate viewpoint has neither been developed in the shape of a narrative based on research and analysis of facts nor has been discussed at public level.

The alternate narrative, if presented, must also generate ‘a great debate’ which could evoke interest among general public especially youth who could produce arguments and counter-arguments from different viewpoints. Such a debate can enlighten the educated elite.

Around 1975, Pakistan Television started a series of lectures about Pakistani culture in which intellectuals from different shades participated including giants like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Prof. Karar Hussain, Dr. Nabi Bakhsh Baloch, Kaneez Yousaf and Bano Qudsia. These lectures started a debate in the press and intellectual circles about the Pakistani culture and its genesis. Do we now have any such debates on cultural issues?

Unless we don’t start a debate about our cultural and historical issues we cannot provide new ideological framework to our textbook writer. So the people who want to change the narrative to effectively fight terrorism should first start a serious debate on Pakistani history, culture and present social structure.