The UNIC has portrayed the other side of Pakistan in an exhibition of photographs at the Lahore City Heritage Museum

Most of us who carry a mobile phone in our pockets or handbags, that serves another function of a camera, have become photographers of sorts. We record our observations, impressions and experiences without a conventional skill or mastery in the art of representation. This almost democratic revolution is perhaps the greatest landmark in the realm of art -- something that has made everyone an artist.

It would be interesting to examine the history of photography in Pakistan -- divided between traditional and digital and thus offering a difference between the skilled eye and raw hand. It may also indicate how the shift in approaches towards the subject matter took place. Now instead of formal, arranged and orchestrated pictures, a casual and relaxed manner of photography (like a selfie) is preferred. Compared to earlier attempts in capturing the ethnic, exotic and authentic visuals of a society, the spread of photography has generalised the choice of subject matter in our age.

Every image, act or concept is made or thought from the standpoint of a political position. Thus the simple act of pressing a camera button denotes a person’s idea and ideology. This can be observed in the way a society is presented in the electronic and print media.

Normally, a country is introduced through the visuals associated with it. When people actually cross borders, they perceive the new surroundings in the light of their earlier-formed opinions, based largely on the images or visuals they have seen before. This is how the common tourists recognise the historic sites, monuments or famous buildings in a foreign country. They compare the mental picture with the actual place, and become happy or disappointed.

Like a single structure in faraway lands, whole communities and countries are connected with images. For example, Afghanistan and especially the capital city of Kabul was projected during the Soviet invasion as a combination of crumbling houses and haunted neighbourhoods in the Western news. This image was abandoned once the Soviet armies were ousted, and was replaced with mosques, government offices and boulevards with blossoming flowers. But as soon as the Taliban took over, the country was again put in the category of devastation.

After the ‘final’ battle was won and a new government was installed in Afghanistan, the change in the country’s images in the Western media was unmistakably noticed. Like every other developed or developing nation, this country was portrayed with avenues intact, traffic on roads, soldiers in immaculate uniforms, generals with all their regalia inspecting military parades and political representatives wearing nicely cut jackets and in their matching ties during parliamentary sessions.

This creates a false illusion. If the president is shown in a designer’s suits in his palace with expensive chandeliers, exquisite carpets and immense halls, the city of Kabul still contains war-torn areas, with broken houses, dysfunctional roads and abandoned structures. But one has to make an effort in order to recall that side of the reality.

Pakistan too is subjected to media’s modification, mystification or madness. After 9/11, the country has been of special interest for the foreign press. It has concentrated on constructing a specific picture of Pakistan: A state that has cultivated and supported Muslim militants but now is suffering from hostile and inhuman response of these state-grown monsters. Thus the reportage of a bomb explosion, footage of a sectarian shooting, pictures of religious killings and photographs of communal violence seem to satisfy the already-set ideas about a society that is suffering from extremist forces.

All these forms of portraying Pakistan are perfectly logical but, in most cases, this becomes the only view of the country; and people generally tend to forget there may be another side to this society. Near a bomb explosion, there can be a flowerbed with budding roses, or a site of numerous deaths can be close to beautiful mountains, meadows and trees. However, extending the camera’s frame to those pretty areas certainly does not suit the agenda of news agencies reporting the ‘reality’ of Pakistan; because it will contradict the required reality.

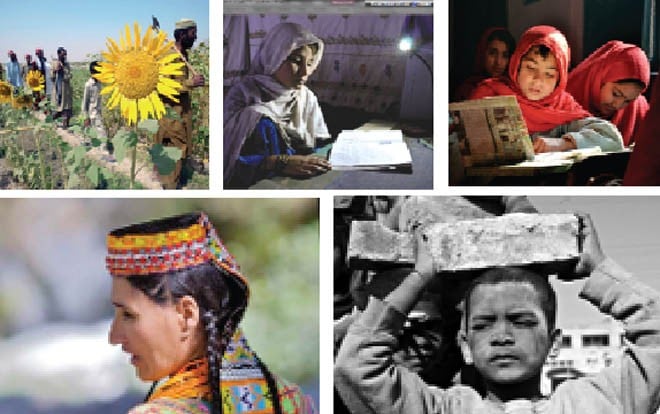

Yet an international organisation, the UNIC (United Nations Information Centre), has chosen to portray the other side of Pakistan. In its recently-held exhibition ‘Human Stories Through Photography’ (from April 16-May 17, 2015 at the Lahore City Heritage Museum) a series of photographs are shown which depict another layer of our existence: that is not sensational, temporal or dramatic, but is equally important because it helps to realise that a society is not reduced to one-dimensional entity.

In the exhibition, one comes across pictures of people busy in their routine chores, for example working in factories, schools, police stations, houses and fields. In one of these photographs, a woman wearing arms bangles is holding a sickle in a field. This unknown female from Sindh not only represents her time and locality, but is connected to five thousand years old heritage as she and the Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-Daro share the same custom of covering their arms with multiple bangles.

In a sense, the exhibition not only extends the idea of Pakistan and its people; it also excavates the links with history. In the exhibition organised by UNIC, one can detect how the artists -- rather ordinary citizens -- have portrayed their reality.

The platform provided by UNIC is significant because it connects and collects visions and views of a diverse range of individuals, some of whom have never considered themselves capable of making ‘art’. The occasion to experience this practice, pain or pleasure, is the most important aspect of this form of image-making which unites us with everyone else and with ourselves too.