Günter Grass provided the amoral and grotesque picture of German history and people’s suffering through his fiction

German speaking geniuses have brightened the intellectual firmament for at least two centuries; from Hegel and Marx in philosophy to Handel and Beethoven in music, from Einstein and Heisenberg in science to Goethe and Brecht in literature, the list is long.

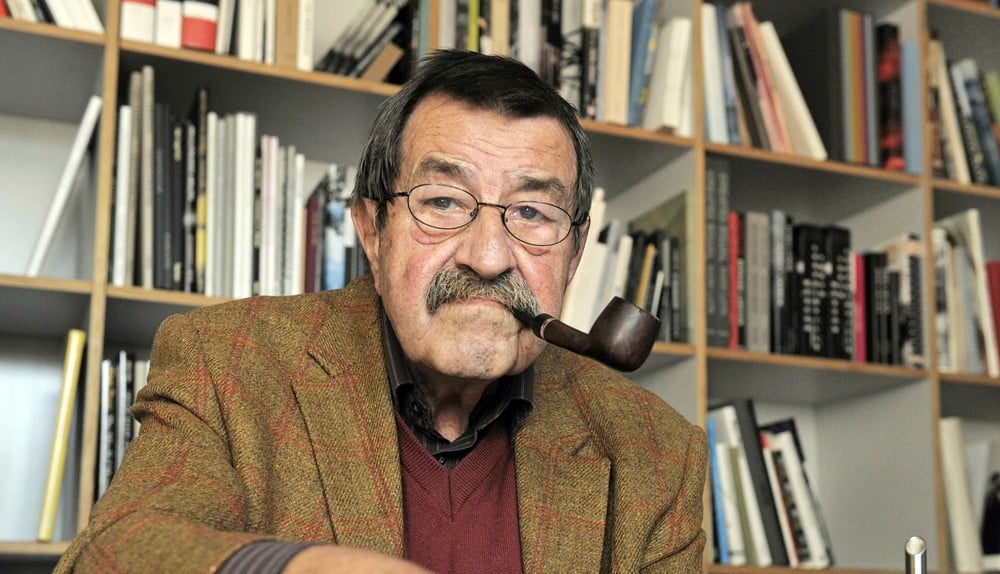

Sadly, the same nation has also produced Hitler and Goebbels who can compete with any bloodthirsty hound in history. But, probably, Pakistan could best benefit from a writer such as Günter Grass who died at the age of 88 on April 13 in Lübeck, Germany, after an illustrious career as a novelist, poet, playwright and sculptor.

Though his oeuvre is enormous, the best and probably the most relevant to countries that have witnessed dictatorships is his Danzig Trilogy consisting of The Tin Drum (1959), Cat and Mouse (1961) and Dog Years (1963). Through this trilogy, Grass became a spokesman for the German generation that grew up in the Nazi era and survived the war. He had experienced the suppression of his nation and then near complete submission of his people to the tune of war mongers.

After the war, at the young age of 30 he went to Paris and wrote his first masterpiece The Tin Drum. The war and its aftermath had profoundly affected the course of German literature and writers such as Heinrich Böll (1917-85) were impelled to come to terms with their historical and political situation. Böll was ten years senior to Grass and already -- at the age of 30 -- had written his first novel, The Train Was On Time, that outlined his war -- time experiences.

Grass, in a way, followed in Böll’s footsteps and joined the Group 47 that brought together almost all important writers of West Germany. Ultimately, both Böll and Grass won Nobel Prizes for literature in 1972 and 1999 respectively.

In comparison with Böll, Grass provided a more amoral and grotesque picture of German history. Danzig Trilogy is set in the Free State of Danzig, a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) and nearly 200 towns in the surrounding areas. The first novel of the trilogy, The Tin Drum, is an excellent portrayal of life in that part of Europe from 1900 to 1950. The narrator of the novel is Oskar Matzerath who writes his autobiography in the early 1950s in a sanatorium where he is detained for a murder he didn’t commit. The story begins in 1900s when Oskar’s mother marries a shopkeeper, but Oskar is not sure about his parenthood and thinks that he might be the son of his mother’s affair with a cousin. Oskar was a curious child born with an adult’s capacity for thought and perception.

The exuberance of this picaresque novel is reflected in a variety of styles; Grass imaginatively distorts and exaggerates his personal experiences. When Oskar is just three or four years old, his putative father declares that Oskar would inherit his grocery shop. Oskar decides, as an act of will and protest, that he would never grow up to inherit that shop.

The novel mixes magical realism with fantasy to show that Oskar is gifted with a piercing shriek that can shatter glass and be used as a weapon. By refusing to grow up he demonstrates his anger at the stupidity and wickedness of adults around him. On his third birthday he was presented with a toy tin drum, followed by many replacements because he wears them out from over-vigorous drumming.

[He remains a child while living through the beginning of World War II, becoming part of a travelling band of dwarves that entertained the troops. Through his tin drum he beats out the story of pre-war Poland and Germany, and the Nazi onslaught on Europe resulting in the defeat and partition of Germany.

Throughout, the drum remains his treasured possession and to retain it he is even willing to commit violence. Grass uses this to portray the creeping militarisation of average families and the attrition of the war years. Oskar’s shrieking voice haunts you and each time his drum is beaten to death you feel the brutalisation of society in your bones.

The next novel in the trilogy, Cat and Mouse, presents historical events through the eyes of a small group of children. The novel revolves around a fatherless child, Joachim, who dreams of becoming a clown and becomes instead a war hero. His life satirises his superiors’ preoccupation with heroism and hero worship. He still wishes to be a clown and holds the regime in contempt; he desires to perform for others and be admired for making other people happy and not by killing others or using violence to become a hero. Through this, Grass explores the contradictions at the hearts of those raised to the rank of hero. The novel has a confessional tone and moves between comic fantasy and brutality.

That was the time when the Indian subcontinent had gone through its own apocalypse, resulting in millions of people suffering from violence and upheaval. Here the writers such as Krishan Chander, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Rajendra Singh Bedi were documenting their own experiences, but the monumental scale with which Grass encompassed the tragic events in his trilogy is still missing in Urdu. Quratul Ain Hyder and Abdullah Hussain may be credited with writing their magnum opuses in Aag ka Darya and Udaas Naslain, but the craft with which Grass enmeshes reality and fantasy is superb.

In Germany, it was not easy to show the mirror to the nation that had tried to and nearly did conquer the whole of Europe, and Grass did it and earned the role of ‘conscience of his generation.’ His dwarves were the whole generation growing up in the first half of the 20th century and drummers were the folks who entertained the oppressors; his shriek was a loud protest but it came from a midget. You read his novels and realise how close he comes to portraying similar situations in many third world countries that went through military dictatorships and how most of the adult population submitted to them, apart from a lone shriek coming from an insignificant being or a drum being beaten beyond the last mountain.

The Tin Drum was adapted into a movie made in 1979 which won an Oscar Award for the best foreign language film in 1989.

During his last years, Grass kept his activism by criticising Israel for its atrocities in Palestine, for which he was not admired by many. In 2006 he revealed that as a 17-year-old boy he had joined Waffen-SS, an armed wing of the Nazi party that served alongside the regular army. At this revelation the critics jumped on him for hypocrisy, but he said he was just 17 and had no other option.

Writers such as Grass truly serve as the conscience of a nation. Sooner or later the nations have to wake up to their past and admit the atrocities committed by their rulers and officers. History usually presents a dry and unimaginative picture of events. Literature, especially in the hands of a writer of Grass’s calibre, becomes a moving account of people’s sufferings and their collaborations in crime.

Grass created characters that defied logic, but appealed to emotions and enticed to grope one’s heart. If you have not read The Tin Drum, watch the movie and you will feel the shriek much after the movie has ended.