Mohsin Shafi dwells on this course of creating newness in art in his recent exhibition at Taseer Art Gallery, Lahore

There is an unspoken deal among people who walk in public parks every morning -- they usually keep to their left. But in the park where I walk, there is this woman who walks on her right side. This causes inconvenience to all but I do admire her courage because, despite sensing the discomfort of others, she sticks to her chosen path.

A quality that puts people at unease in ordinary spheres of life is highly appreciated when it comes to the realm of art. A person who deviates from the normal course and carves an uncommon scheme is perceived as an artist of merit, compared to those who follow the routine.

It would be relevant to understand how the idea of newness got so important in art because, in many cultures, it was never even expected that a creative person must invent or innovate. In such cultures a form of perfection was preferred more than making a unique or unexpected entity. Thus in the practices of past -- from medieval European illuminated manuscripts to miniature painting of Mughal courts, traditional tunes of the West to Indian classical music -- artists were repeating or re-interpreting existing forms in order to offer examples which could surpass earlier attempts.

George Bernard Shaw observed this aspect of art as: "…in art the highest success is to be the last of your race, not the first. Anybody, almost, can make a beginning: the difficulty is to make an end, to do what cannot be bettered."

The impulse to produce unique concepts could be related to an age which revolves around manufacturing and marketing industrial products. The aspiration for the new in art can not be completely delinked from the factory production phenomenon.

But anyone who is in the business of making art knows that innovation does not appear from the void. It is always about transforming old into a revised format -- much like walking, since it is not possible to move forward unless one foot is pushed back.

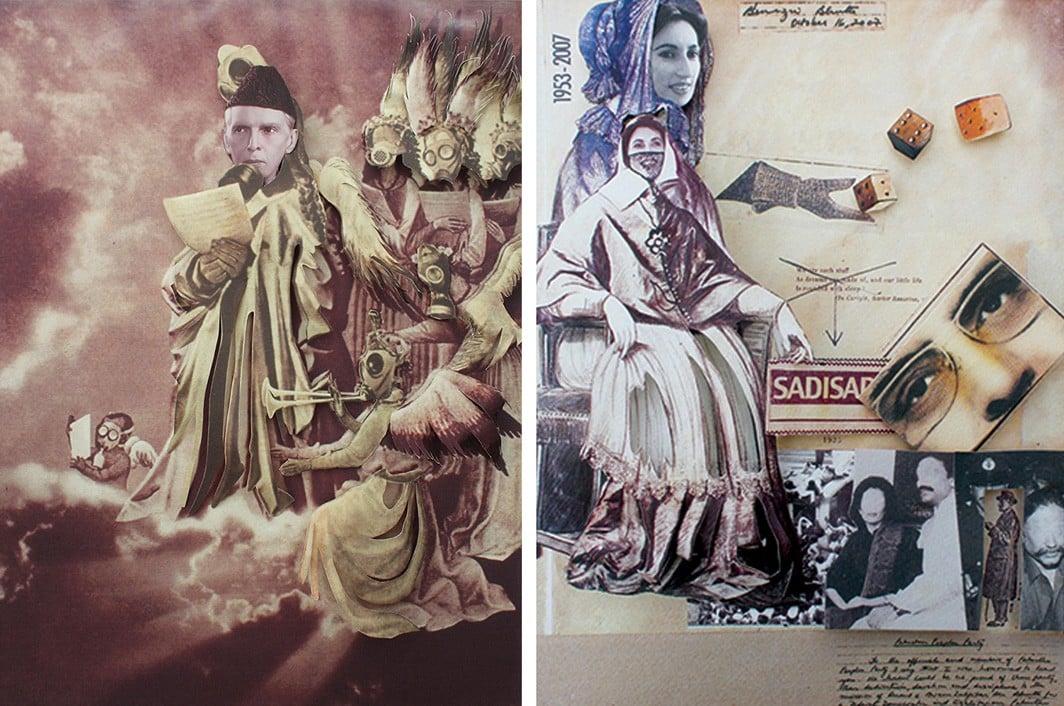

Mohsin Shafi dwels on this course of creating newness in his art. In his recent exhibition at Taseer Art Gallery, Lahore several assemblages, based on prominent political figures, were displayed. Some works were constructed with layers of paper cut-outs fixed at a small distance from each other, thus making a structure that can be contained in a box. A few others were two-dimensional collages.

Whether three dimensional or flat, all works were derived from collages of Dada Movement; hence the title of the exhibition, Sada-ism, is a pun on appropriating Dada as Our (in Punjabi). However, the relationship between the art from the first half of twentieth century and Shafi’s work is not only about combining ready-made visuals; it connects with the content too. Dada commented on the politics of their times and Shafi appears to be doing the same in his collages and assemblages.

Mohsin Shafi, from the time of his postgraduate studies at NCA, has been interested in exploring the link between the sacred and banal. In one of his past works, he put laptops inside conventional cloth covers which are used to keep sacred books. In another video, the recitation of 99 names of God (probably an Egyptian TV production) was mixed with a sequence of 99 TV channels changing constantly. The artist has been questioning the social constructs in a culture which may have their basis in custom but not in religion.

In the present body of works, too, Shafi is challenging the notion of sacred, but within the domain of politics. Thus one comes across features of former military ruler Pervez Musharraf blended in with Marcel Duchamp’s Moustached Mona Lisa. Similarly late dictator General Zia ul Haq replaces the figure of Hitler in various works. Along with these autocrats, undisputed personalities such as Jinnah, Iqbal, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto are also composed in several works. For instance, the face of Benazir Bhutto occupies the self-portrait of Farida Kahlo (titled, Bay Nazeer Kahlo). It is also composed in the photograph of Mexican painter (Bibi on White Beach). In another work, she is holding a Chinese fan and surrounded by birds (Nucleus, an appropriation of Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even) or her face is inserted in the portrait of English Queen in a UK stamp (God Did not Save the Queen).

Some other works include faces and figures of Pakistani politicians, ranging from Sharif brothers, to Bilawal Bhutto, Yusuf Raza Gilani, Sheikh Rasheed, Maulana Fazul ul Rehman, Tahir ul Qadri, Altaf Hussain and Imran Khan. Besides a few enigmatic pieces, most of these works seem closer to currently popular political comedies on our news channels in which different actors impersonate the party leaders and, instead of offering some decent political critique, entertain the public by ridiculing members of the parliament.

On surface, these programmes appear as signs of free speech and a sense of humour. But deep down these are conscious attempts to discredit democracy by ridiculing political leaders across the board. They are careful enough to avoid extremist or sectarian figures (so no Hafiz Saeed, Mullah Omer or Khalifa Abubakar Al-Baghdadi!) or prominent members of media, judiciary or establishment.

This order of things is acceptable on prime time TV but an artist must move away from such clichés, especially when he is working on the aesthetics of Dada that prided itself on defying the established order. Because it is not only state but society too that dictates dogmatic doctrines and orthodox ideas.

Perhaps the problem of Mohsin Shafi’s art practice, more than its choice of characters, is its reliance on one idea and reproducing it in various guises. Thus despite the difference of face and figure, the work appears identical with minor changes in technique, concepts and the artist’s position.