Development partners and the IMF continue to demand fiscal reforms by provincial revenue administrations

Pakistan’s overall tax-to-GDP ratio has been hovering around 10 per cent for the past decade, which is approximately 5 per cent lower than the average of comparable economies. Despite a large tax base available with all provinces, they collectively contribute only 7 per cent in overall revenues.

Our development partners and the IMF continue to remind us regarding the desired efforts by provincial revenue administrations for fiscal reform in the country.

This year provinces will announce their budgets and will also enter into an important renegotiation of National Finance Award. It is important that they should set clear objectives for budgetary reforms, which may include: revenue mobilisation in untapped productive sectors, e.g., agriculture, services and property, increased financing for high priority expenditures, e.g., education, health and pro-poor infrastructure, and improving public finance management particularly procurement systems.

On the first objective, i.e., tapping new productive sectors for revenue, provinces have continued to rely on some very old tax rates charged under property taxes, stamp duties, motor vehicle levies, agriculture income tax, electricity duties, professional tax, capital value tax, infrastructure cess, and entertainment duty. Apart from these, the non-tax revenues of provinces come from irrigation, community services, law and order and general administration.

This shows that the largest sub-sector of Pakistan’s GDP (services sector), which can be tapped by the provincial governments, is not being brought to their advantage. Some of the large sub-sectors under services include: wholesale and retail trade, electricity and gas operations, agriculture and extension services, transport, storage, communications, ownership of dwellings, banking and finance.

Currently, none of the provinces have conducted a census of services establishments or services sector incomes at provincial level. This has also given rise to a large informal sector in services which includes: private education academies, tuition centres, private medical hospitals and clinics, public transportation, accounting and legal support, retail outlets, beauty parlours, etc.

As provinces embark on implementing and revising their province-level legislation on services sector taxation (e.g. Punjab Sales Tax on Services Act 2012; Sindh Sales Tax on Services Act 2011) they have identified some sources of incomes accruing to: hotels, clubs, caterers, advertisements, telecom, insurance, banking companies, non-bank financial institutions, stock brokers, shipping agents and courier services. However, under several of these heads provinces are headed towards friction with the federal government.

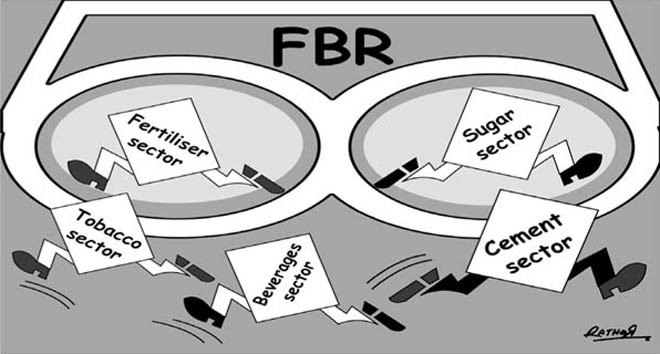

There are statutory regulatory orders (SROs) enacted by the federal government which either exempt or allow preferential rates on several income heads mentioned above. Similarly, the business community is already complaining about double taxation (by federal and provinces) under excise duties.

Some frictions also occurred when Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) asked provincial government to collect withholding tax at higher rates on registration and transfer of vehicles. This, according to the government of Sindh, led to decline of registration of new vehicles, vehicle transfer cases, and road tax payments in Sindh.

The Tax Reforms Commission (TRC) has also recently pointed out that there is incidence of double taxation particularly in services sectors. They have recommended that federal excise duty should only be charged on goods and services should be eliminated from this schedule with only exception where provincial sales taxation is not covering certain services rendered.

The TRC had also pointed out that land utilisation data in most provinces is not accurate. Correcting this data can, in fact, help in comprehensively estimating provincial tax base for property and real estate. We also understand that the work on provincial income accounts is not robust. For example, one will struggle to find official estimates of GDP of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or Sindh provinces.

The sector-specific value added is harder to find even for Punjab province. The provincial Bureaus of Statistics do not have formal mechanisms for data and information sharing on a regular basis. Their coordination with the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics is also sporadic.

Another area of concern is the fragmented manner in which taxes are being collected at the provincial level. For example in the case of Sindh, taxes are being collected by: a) Excise, Taxation and Narcotics Departments, b) Board of Revenue, c) Sindh Revenue Board and d) government of Sindh directly collecting levies (e.g. electricity duty).

Such fragmentation has been addressed to some extent in Punjab. In September 2014, the government of Punjab had decided to merge all provincial tax departments in to Punjab Revenue Authority. The excise and taxation department and Punjab board of revenue will be phased out in the next two years.

The efficiency of tax collection at provincial levels also needs attention. For example, Sindh Tax Revenue Mobilisation Plan 2014-19 correctly points out that 9 out of the total 15 provincial taxes in Sindh render 99 per cent of collected revenues. The remaining 6 taxes only contribute 1 per cent. Such taxes should be reviewed, simplified, or consolidated.

All provincial governments will need to undertake some key reforms to improve resource mobilisation. First, provincial revenue authorities need to establish a census-based baseline of tax bases for each of the provincial taxes. The baselines should highlight the current sector-wise tax gaps, administrative efficiency, and sector-wise effective revenue potential. The coordination across the provincial revenue collection bodies should also be reviewed.

Second, introduction of IT-based business processes for tax compliance should help in reducing the human interface between tax payers and payee. This will also facilitate a reduction in avenues for rent-seeking and corruption. While automation of wealth sources, including land ownership is important, however, IT-based innovations can help in detecting sales transactions in unorganised sectors, e.g., retail shops, restaurants, and beauty parlours. The GIS-based validation of land holdings, commercial wholesale and retail activity has also been proposed by some experts.

Third, provincial revenue authorities will need to develop internal capacities for analysis of data and information from audit, monitoring and evaluation functions.

For example, there are clear information gaps in: a) taxes that may be received from unorganized sectors, b) arbitrariness in assessment of provincial levies such as stamp duties, CVT, and other registration fees, c) assessing genuiness of the holder of property at the time of registration and transfer, d) assessment of market value of fixed assets and property, e) assessment of property tax on current rental value, f) tracking current status of property i.e. under commercial, residential or government use.

Fourth, revisit any exemption and preferences allowed under provincial tax laws. The provinces should also ask the federal government to remove such allowances (allowed through SROs) on incomes now forming tax base of provincial revenues.

Finally, a concerted effort is required to improve tax payers’ information regarding provincial taxes. The provincial revenue authorities should also expedite work on one-window operations and tax payer facilitation centres. A related point is that provinces will also need to strengthen tax related grievance redressal mechanisms which are almost non-existence in practice.