I do not mind saying that of all the creative works I have undertaken in my life this has been the one which did not make me squirm

If you read a piece of, let us say, Mir Amman’s prose followed by the highly ornate prose of Suroor’s Fasana-i-Ajaib, you have to evoke the stylistic difference between the two authors without resorting to histrionics. A sensitive reader should only bring out the flavour of the style and not milk it, as many of our performers do. The reader’s task is to convey the substance of the text -- as well as the sub-text -- and not embellish it with his own mannerisms. This can only come about if he has developed the sixth sense of being fully involved with the text while retaining the ability to remain detached from it.

* * * * *

Urdu is not my mother tongue, that is to say my mother did not speak to me in Urdu. My father did, mostly when he took me along on his evening walks. He saw to it that my sheen-qaaf was in order. It was because of this that at school I was chosen to recite the school motto at the morning assembly. The scholar-poet Pandit Brijmohan Dattatriya Kaifi, a friend of my father, influenced me as well. He was a wizened old man but his voice was firm and his Urdu was impeccable. He was always dressed in spotless kurta, churidar pyjama and a lightly starched muslin dopalli topi through which his bald head gleamed.

The man who influenced me the most about how to speak Urdu was Rajah Sahib Mahmoodabad, one of the most civilised men I have ever come across. His vowels had a sweet roundness and words fell from his mouth trippingly. I do not remember his sentences ever including any English words other than the names of tube stations.

I met Rajah Sahib through Atia Habibullah, the real name of the writer, Atia Hussain, the author of Sunlight on a Broken Column. He was a frequent visitor at Atia’s flat in Chelsea; they had been family friends.

In those days Atia and I were the leading performers in the BBC Urdu Service weekly dramas. She had one of those rare ‘nightingale voices’ which stay in your memory for ever. She lived not far from me and I used to drop in on weekends around mid-day to have a cup of coffee, which I had to make myself. Not only that, I had to wash the cup, the saucer and the spoon, dry it with the fancy tea-towel that hung absolutely straight over the oven rail and place everything in its precise place, making sure that the tea-towel did not hang crookedly, before leaving the kitchen. Atia was fastidious about her kitchen.

In the mid-1950s Rajah Sahib Mahmoodabad had taken up residence in Oxford where his son, the future Rajah Sahib, was studying at one of the colleges. When he visited London he spent most of the time with Atia whom he treated with a mixture of admiration and insouciance.

When I was first introduced to him, I said my Adab with my head bowed. He responded courteously and then turned to Atia to say, "In se bhi tum git-pit git-pit main baat karti ho?" (Do you speak to him in English as well?) It was a dig at Atia for she always spoke to her children in English which made him wince. "Nahin, nahin," she said "Yeh to bohat achchi Urdu boltay hain." I was chuffed. "To aao Mian, baitho", he said with a warm smile.

More on: Looking back

I had several occasions to be in his company during the summer of 1955. He was a short man with balding hair, a noble brow, alert eyes and a laid back sense of humour. His speech was precise and well-modulated. I loved listening to him. His variations in pitch within a given sentence were astounding. It was not just his intonation but the lilt that accompanied it, which left a deep impression on me. We call it lehjay ki loch (pliability) I have not come across many people who had the same loch.

* * * * *

My first Urdu recital was sponsored by Urdu Markaz in London in 1984. It was held in the main classroom of SOAS and was received enthusiastically even though I mispronounced a few words. An oriental audience is generous by nature. I chastised myself for not having been more careful. Since then I have rarely been at fault with my zer-zabar, (phonemes).

Mansoor Bokhari, the head of EMI Pakistan, was in the audience. He approached me afterwards and said that EMI would like to record Faiz’s verse in my voice. I said I was willing, provided EMI also let me record Ghalib’s letters to his friends. He readily agreed.

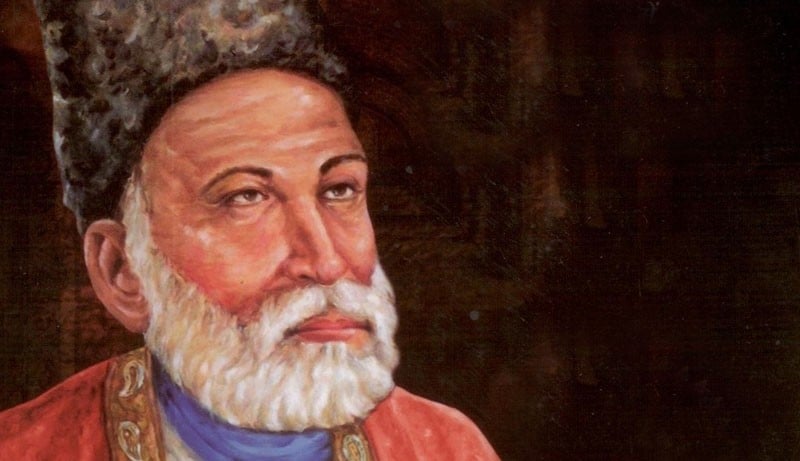

I now plunged into Ghalib’s inimitable, delectable prose. Here, I had the great advantage of having the guidance of the great scholar cum writer cum poet, the late Dr Daud Rahbar, who had spent six years on translating and annotating most of Ghalib’s letters into English I selected two of Ghalib’s best known letters, recorded them on my modest tape recorder, and posted the tape to Dr Rahbar in Boston. His reply took the wind out of my sails. In a most affectionately admonitory manner, he wrote:

"…If ever a poet had lived up to Lessing’s advice: ‘write as if you are speaking’ it is Ghalib. In his letters we have exquisite specimens of Urdu conversationlism. In my childhood I enjoyed the privilege of being in the company of many elders of classic personalities. Their style of conversation echoed Ghalib’s culture. The letters were written by a man to whom the social graces of a life of leisure come naturally. In your rendition you must try and reproduce the leisurely effect of the original. A crisp and racy manner will not do ‘Bas Sahib ko bussab mat banaayay…’ You cannot afford to throw away a single syllable of the word he uses. Your diction has to be perfect and faithful to the period.

Ashamed and abashed, I began to work again and after a week or two sent him a second recording. His reply was prompt: "You have now become too conscious of words; they seem to be dominating you. The words should stand like footmen in the presence of a Duke and assume life as he beckons them to…"

It took me the best part of two years before I thought I was ready to record Ghalib ke Khutoot in three volumes. I do not mind saying that of all the creative works I have undertaken in my life this has been the one which did not make me squirm. Could I have done it if I was not in England? I doubt it.

(concluded)