The miniature of ‘Inayat Khan Dying’ as his inspiration, Suleman Khilji expands the idea and scope of history in his solo show at Sanat Gallery Karachi

Mughal Emperor Jehangir wrote about this ailing figure Inayat Khan in his memoir who "in addition to eating opium also drank wine when he had the chance. Little by little he became obsessed with wine, and since he had a weak frame, he drank more than his body could tolerate….. Finally he developed cachexia and dropsy and grew terribly thin and weak."

Apart from giving this detailed account, he ordered the court painter Balchand to draw the likeness of Inayat Khan. What emerged was a drawing, perhaps one of the best linear works of Mughal School, along with a painting in colour.

This miniature which has inspired many painters over centuries still enchants the artists and this includes Suleman Khilji who created his recent body of work (shown from March 6-15, 2015 at Sanat Gallery, Karachi) based upon this single art piece from the Mughal era. The lean and starved body of a man tucked in sheets on a bed with large cushions in the background has captured the imagination of a painter who perceives human anatomy as a metaphor.

In fact, the history of art can be read as the history of human expressions conveyed through manifesting human bodies. In all cultures and societies, man is portrayed in diverse schemes. Compare the stick-like people drawn by African tribes and the naturalistic torsos made by Greek sculptors of Classical Age. Or match the human forms in the art of Aboriginal Australians with the flowing figures found in Chinese ink paintings. Or equate the Renaissance rendering of anatomy with the refined depiction of kings and princes by the painters of miniatures in India and Iran.

Each culture perceived and portrayed the human figure in a unique style, depending upon the conviction and imagination of the people. The various representations of Jesus Christ serve as a good example. In the miniatures during the period of Emperor Akbar, historical figures such as Alexander the Great and mythological characters like Krishna were painted wearing costumes of sixteenth century India and with features not dissimilar to the locals.

One common factor, even in this diversity, is the association of death with pain and grief. In Khilji’s new works, the attitude towards death as a subject holds a peculiar significance. Picking the miniature of ‘Inayat Khan Dying’ as his source of inspiration, Khilji has produced works dealing with the idea of death, disease and deprivation. The original drawing is an unusual specimen of realism in the traditional miniature painting. The depiction of a person on the threshold of extinction is so convincing that one can glimpse the existence of death by looking at the body on the bed.

Khilji has created a total of 21 canvases and works on paper, all variations on the initial image but extending it to contemporary times. Inclusion of shiny stickers of stars, patterns of a bed sheet with cars and English words, and many models wearing modern dresses allude to how an artist reinterprets heritage and deconstructs past. However, unlike most miniature painters who have been reviving, rather resurrecting, the genre with multiple devices and in various guises, Khilji has approached the form from history for its potential as a symbol related to its role and relevance in the past and future.

In his work, Suleman Khilji expands the idea and scope of history with inclusion from other sources in world art. For instance in ‘Marat and Inayat’, two men -- one dead (derived from French painter David’s painting) and other on the verge of annihilation -- are composed side by side. So, what one views is not a clash of civilization but a combination of basic human phenomena. Both men, who are real characters in recorded history, are composed next to each other in a way that the work on paper becomes an elegy to death beyond borders.

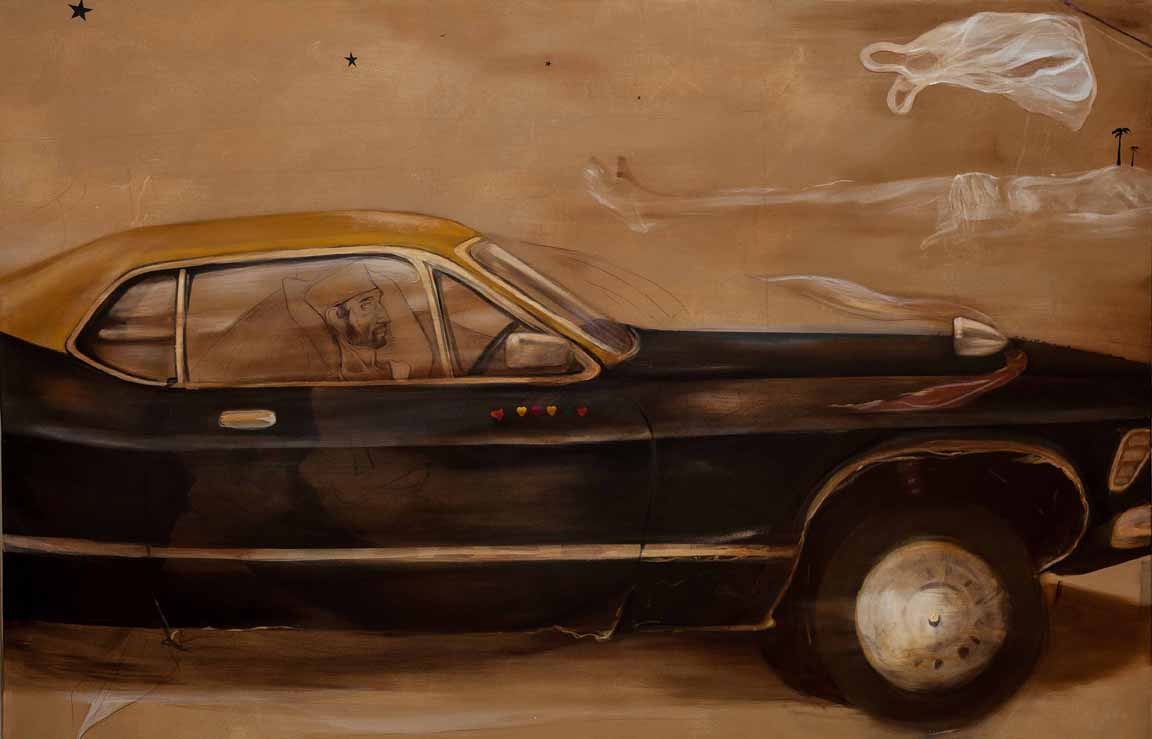

The aspect of blending time and space is as important in the art of Suleman Khilji as his ability to render minute details. In one of the works at Sanat Gallery, the dying figure of Mughal era is inserted inside a car moving in great speed. In another work, the last Mughal Emperor Bahauddur Shah Zafar is drawn (from a photograph which is probably the only one of the ailing, suffering and helpless deposed old man) in the same settings of cushions, bed and sheet, that echo the drawing of Inayat Khan.

This work particularly and others generally remind that the death in Khilji’s aesthetics is not about recreating tradition but is a pictorial device to denote the present. The bomb blasts, suicide attacks and sectarian killings depict a society’s fascination with death. More so because death is often believed not be a chemical conversion of atoms but a passage from temporary existence to eternal life.

In a sense, both the artists and those opting for terrorist acts share this desire to ensure a future after departing from this world of illusions and deceptions. But the two have different visions of death. Terrorists view it as salvation whereas the artists investigate the tendency inherent in a certain group or sect to kill. They examine the society’s miseries and present what is hidden or too disturbing to accept, admit and acknowledge.

In Khilji’s work, the depiction of death is a celebration of life because all characters, including the portraits of his acquaintances from Lahore and rendered in the posture of Inayat Khan, appear humorous, uncanny, resisting their fate. Similarly the dying figure in a moving car or against a bed sheet becomes a symbol of triumph of life over death.

In reality, Khilji is performing the same task that Balchand did in Jehangir’s court -- bestowing longer life to a man who was merely bones and skin and must have departed the world a few days after the completion of this drawing in 1618. Art ensured his eternity. In a similar way, the life of art seems to be the real aim for the artist from 2015, who has turned individuals from his own environment into a tribe of dying persons. But as long as the work remains intact, these people won’t age or disappear or disappoint!