Despite having a conspicuous representation in the Pakistani socio-cultural landscape, Tablighi Jamaat has thus far eluded a scholarly gaze. Information available either in print or on the internet is sparse and brief.

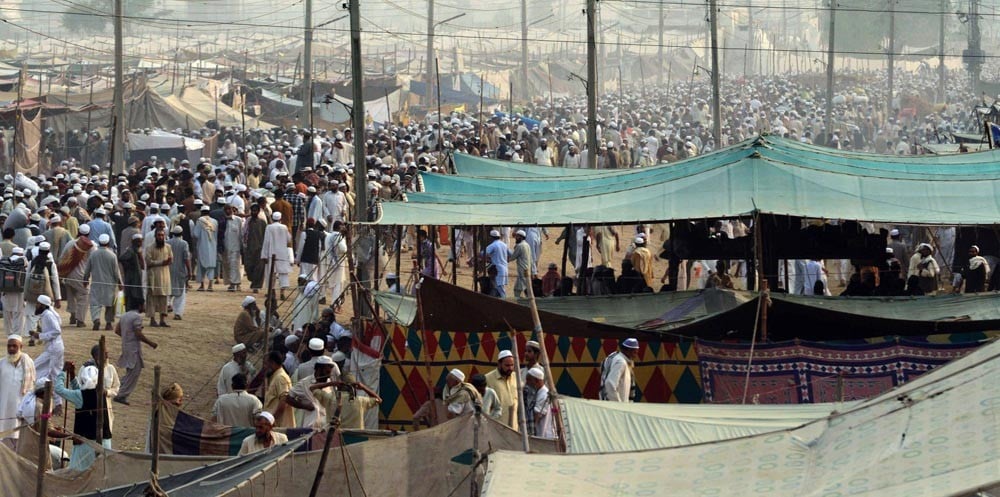

That is surprising because with the Pakistan chapter of Tablighi Jamaat set up after independence, for many years Tablighi ijtima (gathering) at Raiwind was the biggest in scale. Bishwah Ijtimah in Bangladesh overtook it much later. Only Maulana Tariq Jamil’s omnipresence on various tv channels belies that assertion. Otherwise just the word of mouth is deemed sufficient for disseminating the tablighi message, in a bid to emulate the method of the Prophet [pbuh].

Interestingly enough, Tablighi preachers are not shy of using loudspeakers in their mission to proselytise. Similarly, while travelling, they are happy to avail modern transport facilities, which were not used in the days of the Prophet.

Thus the adherence to the ways of the Prophet is quite selective.

The accounts of its annual gatherings or the minutes of the Shura meetings are not made public. That probably is why no study underlining its influence on Pakistani populace has been carried out yet.

Yoginder Sikand, an Indian writer and academic on contemporary Islam, may be the sole exception. He has produced an insightful study on the history and its evolution titled, The Origin and Development of the Tablighi Jama’at (1920-2000): A Cross Country Comparative Study. But this too excludes the Jamaat’s role and influence it has come to wield in Pakistan. His Indian nationality was an impediment in securing a research visa for Pakistan, therefore, that omission came about.

Nevertheless, Sikand must be commended for producing a brilliant piece of work in which he has mapped the colossal spread of the Jama’at’s proselytising activities across continents. The exclusion of Pakistan notwithstanding, his study has a wide scope and spectrum.

However, any watchful social analyst would vouch for the Jamaat’s soaring presence in every echelon of Pakistani society.

Tablighi Jamaat and its peculiar method of proselytisation in Pakistan have earned it a large following, which cuts across the bounds of caste, creed and kinship. That undoubtedly is a remarkable feat. The Jamaat is reputed to have always steered clear of any political allegiance. All its members try to play neutral if not absolutely indifferent in the political debate, which needs some doing because people of this country are incredibly political. People’s engagement with politics is generally through its condemnation. But then condemning politics itself is an act of politics.

Tablighi Jamaat thinks the same about fiqh (jurisprudence). Although it emanated from the Deobandi sub-school in the Hanafi fiqh, no particular interpretation of Islam has been preferred over the other -- since the Quran and Hadith from which various denominations derive their authority are considered one and immutable.

It must be added here that Fiqh-i-Jaffaria (Shias) are not countenanced among its ranks. In such a complex social scenario, Tablighi preaching is circumscribed to a handful of fundamentals. It does not get into any cultural or historical aspect in which any religious message has to be understood to mend and mould local traditions. The Tablighi nisab (curriculum), comprising a collection of books, is recommended by the Tablighi Jamaat elders for general reading. This set includes four books namely Hayatus Sahabah, Fazail-e-Amaal, Fazail-e-Sadqaat and Muntakhab Ahadith.

Tablighi Jama’at was founded by Muhammad Ilyas al-Kandhlawi, a student of Rashid Ahmad Gangohi, one of the founders of Dar ul Ulum Deoband. Initially Maulana Ilyas named it Tehreek-i-Iman (the movement for faith). Primarily, it aimed at spiritual reformation by working at the grassroots level, reaching out to Muslims across social and economic spectra to inculcate in them the awareness about the fundamentals of Islam. For that purpose the Tablighi elders put together six principles, Iman, Salat (prayer), Ilm-o-Zikr (the knowledge and remembrance of Allah), Ikraam-e-Muslim (honouring a Muslim), Ikhlas-i-Niyyat (sincerity of intention) and Dawat o Tabligh (inviting and preaching).

Tablighi Jamaat’s inception is stated to be a response to the perceived deterioration in the moral values and abnegation from the pristine practice prescribed by the Holy Prophet. Muhammad Ilyas raised the slogan which subsequently became the centre-piece of the Jamaat’s ideology: Aye Musalmano Musalman Bano (O Muslims, become Muslims). This was meant to unite Muslims in embracing the Prophet’s lifestyle.

It is important here to mention the emergence of the Jamaat coincided with Hindu revivalist movements, like Shuddi and Sanghatan, which aimed at reconverting some Muslim communities like Malkhana Rajputs of Eastern UP and Meos of Mewat. Such conversions were not many but Muhammad Ilyas got concerned over the fuzziness that blurred the boundaries between Hindus and Muslims.

One also should not lose sight of the fact that in 1920s when the Jamaat was established, Hindu-Muslim tension had peaked in Northern India. Thus the circumstances were ripe for such an organisation to take root. It therefore gained a phenomenal following in a relatively short period and nearly 25,000 people attended the annual conference in November 1941.

The movement expanded from local to national to international, and now claims to have over 20 million followers in over 210 countries. Its pan-Islamic orientation makes it inimical to the fundamentals of the nation state. Unequivocal stress on the Islamic identity, while discounting spatial, cultural and social aspects, makes the Jamaat operative a free floating missionary with skewed and simplistic prognosis for all social ailments. Such complex social structures, like Pakistan, do not make sense unless their culture and history are taken into account while devising any plan for reform or even spiritual rejuvenation.

Music, for instance, has been a part and parcel of the Muslim tradition in South Asia. Quite contrary to the methods of the Jamaat, many conversions have taken place at the hands of musical maestros like (late) Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Sain Zahur and Indian classical musician Ghulam Muhammad. Similarly Indian Music icon A.R. Rehman despite being a devout Muslim continues to compose music.

How would the Tablighi elders respond to such developments? Things are not that simple in a world riddled with complexities of myriad kind.