A voice from the past and a missing piece of history

Dear All,

The discovery that two prominent and highly placed British diplomats were actually Soviet spies was one of the dramatic high points of the Cold War. The defection of Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess in 1951 shook the anti-communist intelligence establishment: both men were trusted MI6 agents who had actually been moles at the very heart of the establishment.

Maclean and Burgess were the first of the ‘Cambridge spies’ to be identified and exposed. But in the decades that followed, the flamboyant Kim Philby and the art historian Sir Anthony Blunt were identified as the ‘third’ and then the ‘fourth’ man (in 1963 and 1979), and it now seems fairly widely accepted that the fifth man was probably another highly placed intelligence official, John Cairncross.

After Burgess and Maclean’s defection snippets of information about their life ‘behind the Iron Curtain’ filtered out to the west, the most interesting was perhaps written by Alan Bennet based on the actress Coral Browne’s account of her chance meeting with Burgess while she was on tour in Moscow in an RSC (Royal Shakespeare Company) tour of Shakepeare’s Hamlet in 1958. The TV film of An Englishman Abroad was a fascinating glimpse into Burgess’s life in Moscow, and Alan Bates’ depiction of Burgess was poignant and intriguing: he brought the person and voice of the double agent -- the traitor as he had been labelled -- to life, exiled in an alien land, yearning for English tailoring and other aspects of his past life.

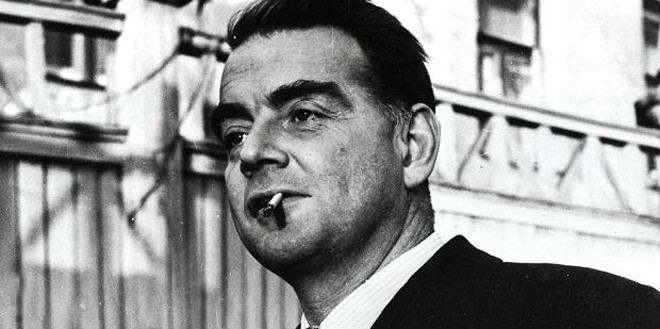

But last week we actually got to see and hear the real Guy Burgess. A startling voice from the past was heard as a forgotten interview from the archives of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) surfaced.

The interview was recorded in Moscow in 1959, more than seven years after Burgess’ flight to Moscow and was broadcast by CBC as the second item on the programme Close Up, coming after an item on poet Edith Sitwell. Astonishingly, despite it being an impressive scoop, the CBC interview went unreported and unremarked upon outside Canada. Certainly no British newspaper made any mention of it at all, and there seems to be no reference to it in any British intelligence files.

But more than 50 years later, the interview was re-discovered by Canadian archivists: it had not even been referenced separately; it was just one item inside the file archived under Edith Sitwell’s name.

The archivists made the discovery in 2011 but the interview was sent for authentication to Britain, to researchers Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert at City University, London. They confirmed its validity and Professor Purvis told the story of the ‘forgotten interview’ on the BBC programme Newsnight last week, viewing the interview along with a former Reuters correspondent (Robert Elphick) who knew Burgess in Moscow, and historians from MI5 and the British Foreign Office.

The man who actually got this scoop -- the only TV interview given by any of the defectors -- was actually Eric Durschmied who, as a young cameraman, had arrived in Moscow, tracked down Burgess (he tried for either Maclean or Burgess), phoned him, went to his flat, met Burgess and persuaded him to do the interview. Newsnight was able to speak to Durschmied about the episode and the film-maker revisited the whole episode, revealing also that after the recording of the interview Burgess had pleaded with him for help to get back to England, even if it meant going to jail.

Durschmied recalled a man who was isolated, lonely and bored; an alcoholic with a deep hankering for the country of his birth. On screen, in this black and white interview footage, you see that Burgess is wearing his old Etonian tie and camel hair overcoat, and speaking in the clipped tones of a British toff.

Elphick recalled how the defector lived his life in Moscow in a "sort of an English bubble", getting his clothes and shoes from England, and never bothering to speak Russian.

This interview is a really exciting discovery: the only instance of one of the Cambridge spies speaking to a western audience, on camera. But it does raise a couple of questions about journalism and journalists. One is the fact that it was either overlooked or else blacked out of the world media, which obviously means that journalists and editors were complicit in the process.

The second is the fact that the interview was secured and carried out by the cameraman Eric Durschmied yet it aired on CBC’s Close Up programme with the show’s host Frank Willis repeating the questions and making it look as if he had actually conducted the interview. This dishonesty of recording questions separately from the interviewee’s answers and making it look chronological in the TV broadcast is one of the basic deceits of television news journalism which, for some reason, remains a practice till today despite its essential untruthfulness.

Why is this still accepted practice half a century later? Why haven’t journalists and editors been able to change this lying practice?

And some thoughts about the archiving process: one view is that the interview remained hidden from sight largely because of inefficient labelling -- i.e. because of carelessness. Yet I tend to favour the alternate view which is that the carelessness and the labelling and referencing omissions were deliberate: a way to hide the interview away from those who might prefer to make it disappear.

Whichever one it was, it is an exciting discovery -- a voice from the past and a missing piece of history.

Best wishes.