Will Kashmir banega Pakistan? Surely this is a question that needs to be asked and a dispassionate effort be made to ferret out an answer

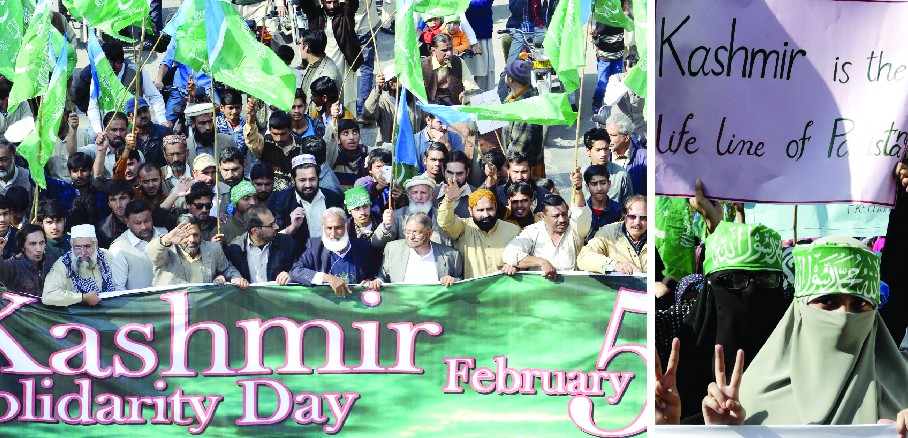

Kashmir banega Pakistan. In the shortest possible articulation, this is the cornerstone of Pakistan’s entire foreign policy in general, and certainly its super-focused India policy.

Behind this six-decade-old oversimplified assertion-made-mission lies a complexity that is arguably driving Pakistan outside the comity of nations whose commonwealth is based on aspirations of pragmatic, mutually assured existence. This especially if you consider how much of the state’s focus, energy and resources are consumed by this passion to merge Kashmir into its volatile embrace, that, in turn, determines the fates of 200 million people today, who underwrite this pursuit whether they subscribe to this duty or not.

Based on their historical distinction in terms of identity and the unfinished agenda of stability that is contemporary politics, the Kashmiris, as any other people on the planet, deserve the right to self-determination. That is the minimum promised to distinct people anywhere on the planet by the post-World War II world. Pakistan links this right to the Kashmiris with the agenda of Partition of the subcontinent of 1947. This makes it a party to the issue of Kashmir. And because the subsequent unfolding decades took Pakistan on paths unplanned for it -- dictatorial and autocratic futures based on the conspiratorial collusion between the unrepresentative military and bureaucratic establishments -- Kashmir and what would become of it came to be the lynchpin of Pakistan’s view of itself.

With the colluding non-representative establishments seeking to manufacture legitimacy for both themselves and their mission, the inability of Kashmir - the political realities of the late 1950s and early 1960s notwithstanding - to cast its lot with Pakistan presented itself as the mission statement for the nascent state of Pakistan. If they couldn’t do it, we’d do it for them.

Hence Kashmir banega Pakistan became the country’s mission.

But six decades down the line and three and a half wars (the ‘half’ being the Kargil war of Musharraf) with India later, the realisation of this mission - which is pretty much not subscribed by the rest of the world - is as distant as the day it was articulated and set in stone.

Bitter truths

But should it have been set in stone? Will Kashmir banega Pakistan? Surely this is a question that needs to be asked and a dispassionate effort be made to ferret out an answer that is no longer couched in truths manufactured by the mysterious overlords of the state. This question also needs to be asked because even a super-expensive nuclearisation of the state has failed to improve the odds of Kashmir becoming part of Pakistan.

Even though it is a taboo question, after the mutually assured destruction parity between Islamabad and New Delhi based on their nuclearisation, the question of Pakistan ever wresting Kashmir from India by force needs to be answered. How many wars has Pakistan won from India to offer an assurance on this count? Wasn’t Pakistan a declared nuclear state when in 1999 the sitting army chief invaded Indian-administered Kashmir in Kargil without even informing the prime minister? What happened next? Pakistan had to send its prime minister on a humiliating trip to Washington to request President Clinton to bail it out of a situation that was leading to an angry India contemplating a nuclear response, a military scenario it couldn’t face or didn’t want to.

Pakistan’s India-centric nuclear prowess based on the sense of self-entitlement to Kashmir dating back to the Partition has taken Islamabad, let’s face it, nowhere near justifying its raison d’etre of being nuclear. In fact, it hurt Pakistan’s plural democratic aspirations as articulated by the political forces in the constitution. How? The same army chief staged a coup against the elected government for being fired from his job for breaching his brief. This within weeks after the same prime minister had rescued the army from a no-win situation. And the same army chief, after installing himself in power did not choose the military option to force a settlement on Kashmir but offered India a surrender on its historical diplomatic policy on keeping the UN a mediator on the dispute and come to terms on a bilateral political option. Of course, that failed too. Woe betide any civilian government that could have ventured the same to India.

Questions without (willing) answers

If the United Nations is as close to helping Pakistan and India settle its dispute on Kashmir as it was in 1948, which in effect means being nowhere considering India has its eyes on the sixth permanent seat on the UN Security Council when Pakistan can kiss Kashmir goodbye, then what’s the answer? For this artificially elusive but embarrassingly painful answer, more taboo questions need to be asked first.

If Kashmir (including the two-thirds part administered by India) is part of Pakistan as part of the Partition agenda, then wasn’t East Pakistan also part of Pakistan proper? If Pakistan is not complete without its ‘jugular vein’ which has been in control of the stated enemy for over 60 years, then how come Pakistan has lived comfortably enough without East Pakistan, which stuck around for 25 years before seceding, for over 40 years since? Doesn’t this bury the concept of ‘Partition rationale’ being immutable?

If East Pakistan force-exercised its right to self-determination away from Pakistan and Islamabad accepted this (by recognising Bangladesh) then how can, theoretically speaking, Pakistan deny this to other ethnic communities within its borders who may demand it? Or was it a Bengalis-only exception? When the Bengalis found they were never meant to be Pakistanis and went their separate, happy way, did that not amount to the end of Pakistan conceptually as it was created by Mohammed Ali Jinnah? And along with it any rationale or agenda of Partition? If so, why continue pinning Pakistan’s future on an agenda that became redundant in 1971?

What if the Kashmiris don’t want to be Pakistanis, or even Indians, and just want to be free, like Pakistanis and Indians want to be free? Will this be acceptable to Pakistan? If so, how, in terms of stated policy? If we failed to make Bengalis happy enough to remain part of the family, how can we guarantee the opposite to our Kashmiri brothers and sisters?

The argument here is not to surrender support to Kashmiris but to stop being the self-appointed arbiters of their fate because that’s the chargesheet we have against India. Kya Kashmir banega Pakistan? It’s clear that it’s the Kashmiris who will decide that, not Pakistan. Or India.