Recounting the women poets of the undivided Punjab, a poetic history that lies buried under male monopoly

Punjabi poetics is unique in adopting the feminine metaphor. From our classics to contemporary poets, the most intimate and challenging verses resonate in this naturalised voice. Female protagonists of our Qissa (epics) poets from Damodar Das to Ghulam Haider Mastana are not only self-assuring and assertive but are full of defiance against male authority and a martialised society.

Najm Hosain Syed summed up this power of choice and rejection assumed by women in a striking one liner: "She stands outsides the cycles of time and society".

Punjab owes all the beauties and colours of its folklore exclusively to its womenfolk. This was the art that kept us enriched and sustained us through centuries of compressions, invasions and annexations. Those nameless women poets of the Punjab narrated our collective consciousness and protected our native identity.

However, the history of Punjabi literature, starting from the 13th century CE, hardly mentions any women poets by name. Dai Phãphal Hafzani (1800-1872) and Jeevan Khatoon Nikammi (1835-1898), two sisters who were writing verses (mainly lullabies as both were attached to our last classical poet Khawaja Ghulam Farid’s family as carers) appear in some studies. But it would be a fair conjecture to say that Piro Preman (Piro the lover; 1832-1872) was the precursor of women’s Punjabi poetry in print.

Ham bha’ay udaase (I am disinclined from the world) cried Piro when she landed in the Gulabdasi Dera at Chathiyanwala, Kasur after escaping from the infamous Heera Mandi of Lahore where it is alleged that she was sold as a prostitute. Her poetic collection comprises of 160 kafis which are full of biographical details. The impression one gets from her poetry is that she was a Muslim who joined Gulab Das (1809-1873) as one of his devotees. Das was the poet and saint who started atheistic Gulabdasi sect. She almost became the co-saint of his secular establishment. Both shared an intimate relationship and lived together inspite of all social and religious pressures. Their joint shrine still exists in the village of Chathiyanwala.

Piro’s poetry shows the influences of Bhagati saints (especially Kabir) and Bulleh Shah. She narrates in one of her kafis that she was abducted and taken to Wazirabad once from where Gulab Das’s men managed her release. During that imprisonment, she wrote this amazing Kafi that expresses her love for Lahore: Vasda chhorh Lahore ko main bande challi (leaving my flourishing Lahore I am going to a prison). She is rebellious, bold and forceful while rejecting all the religious establishments, social structures and caste relations:

JãvNa assi pardes saiyon, Turak HinduaN pare kaahavNa ee

Assi tiyãg jãna mat HinduaN da,nahin TurkaN da kuj dharavaNa ee

Jithe pahuNch Nah Turak te Hinduan di, saiyon ayse makãn mein jãvana ee

Rãm jharokRe baith ke nee, mujra kul jahãn da pãvna ee

(We will go to a foreign land, friends, far away from Turks (Muslims) and Hindus/We will sacrifice the doctrine of the Hindus, nor keep anything of the Turks/Where neither Hindus nor Turks can reach, friends let us reach such a place/Piro says sitting on Ram’s window we’ll dance away the norms of the clan and the world. [Translation: Anshu Malhotra]).

Piro’s kafis are published in the Gurmukhi script by Veer Vahab (Jalandhar: R.B. Singh Publishers, 2012).

After Piro, several women across Punjab made their niche in Punjabi poetry. Bilqis Akhtar Rani, Zeenat and Imam Bibi of Pothohar are among those illustrious women. Unfortunately, very little information is available about these three poets but few of the poetic samples available are enough to register these incredible talents. Following poem by Zeenat written in resistance to the war recruitment by the British army shows the extent of political awareness and metaphorical depths of a village woman:

Chunn chunn la’ay ga’y jawãn sãrey, ajab dhang Bartanvi sarkaar day ni

Kai Barma Sudan tay Maanday wich

India India pa’ay naam pukarday ni

Koi Misr, Iraq, Iran andar

Na’ray maarday dard hunkaarday ni

Khush’eyaaN lakh hovan tere dil Zeenat

Qasid pohnch g’ay Misr bazãr day ni

(They have picked up our youth, this is how British Raj recruits/Many of our boys in Sudan and Burma/yearn for their mother land, [United] India/Many in Egypt, Iraq and Iran, fight and cry out in pain/Whatever happiness you heart yields, Zainab/It’s the slave market of Egypt and buyers have already arrived).

This was the time when women had started using their names in their poetic compositions. Imam Bibi’s devotional verse written for Sheikh Abdul-Qadir Gilani ends with her native reference portraying pains of distance and longing:

KiviN pohnchaaN Baghdad Imam Bibi

HadyaaN sukk gyãN Pothohar andar’

(How can I arrive in Baghdad to pay my respects/My bones have dried up in waiting, here in Pothohar).

Punjabi epics are so innately invoked by Bilqees Akhtar Rani in her purely romantic lyricism in this poem:

Sassi da sidq yaqeen vekho

Tatti rait andar Punnu yaar LoRay

Jatti Rangpur di baitee choochkay di

Ranjhan yaar taa’eeN bailay paar LoRay

Issay Lo’R vich Bhulli Bilqees Akhtar

Yaar kol baithay, andar bahar LoRay

(Look at the conviction and faith of Sassi, she is looking for her darling Punnu in burning sand of the desert/She is the landlady of Rangpur and daughter of lord Chuchak but is out there searching for her beloved Ranjha across the forest/In this pursuit Bilqees Akhtar is totally lost, she is sitting with her darling but still searching for him all around).

Bibi Makhfi (b.1872), Hãjan Noor Begum (b.1880), Karam Bibi Aajiz (b.1893; maternal grandmother of the poet Anwar Masood), Fazal Noor (b.1901; Poet Sharif Kunjahi’s mother), Hakim Bibi HakmaaN (b.1904) and Independence movement activist Begum Salam Tassaduq Hussain (b.1908) and many others contributed immensely to the development of Punjabi poetic sensibility.

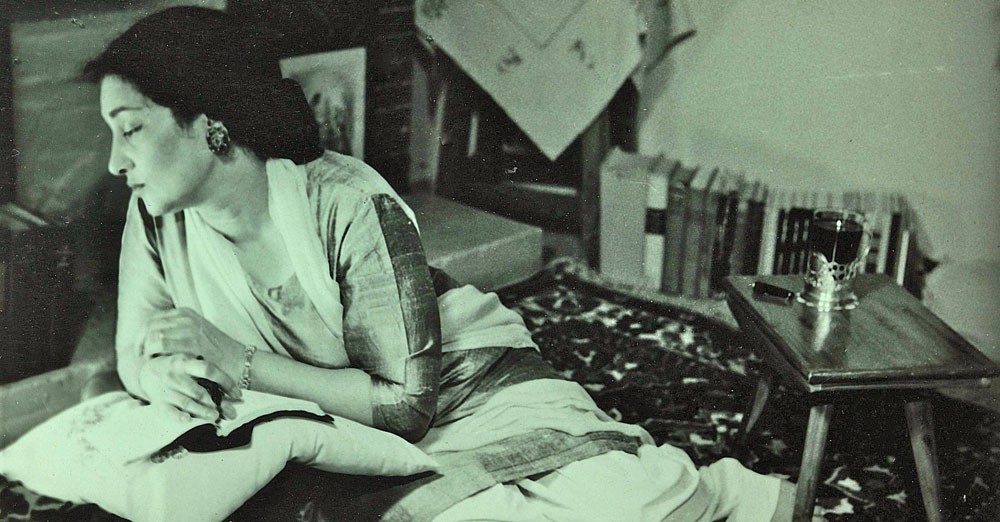

However, Harnam Kaur (1898-1976), Baljit Kaur Tulsi (1915-1997), Amrita Pritam (1919-2005) and Prabhjot Kaur (b.1924) remain major influences of the pre-partition years. Amrita’s ThandiaaN KirnaaN (1935), Harnam’s Arshi KaniaaN (1939), Prabhjot’s Latt Latt Jot Jaggay (1943) and Gujrat born, Kinnaird College Lahore’s graduate Baljit Tulsi’s Neel-Kanth (1944) are the foremost women Punjabi publications.

Most women poets of the post-Piro generation were born in West Punjab and although many among them started writing Punjabi quite late in their lives, they never abandoned their mother tongue. Santosh Sahini (b.1918 in Bhera; wife of actor and writer Balraj Sahini), Sheila Gujral (b.1924 in Lahore; wife of ex-Indian Premier IK Gujral), Surjit Sarna (b.1930 in Lahore; mother of diplomat Navtej Sarna), Mohinder Kaur Gill (b.1937 in Multan; mother of singer Rabbi Shergill), Kailash Puri (b. 1925 in Rawalpindi) and Kana Singh (b.1937 in Gujjar Khan) are some of the names who liberated our literary imagination and enriched the Punjabi poetic landscape.

Pain and agony of all these uprooted daughters of the West Punjab was captured by Parbhjot Kaur in one of her remarkable poems. She was born in Langrial, district Gujrat and earned her graduation from Khalsa College for Women, Lahore before partition. Her poem Janam BhooN di Yaad Vich (In the memory of my birthplace) opens with a whimper:

Aaee yaad Lahore di, pain dillay wich ho’l

Pujji pehlaaN jind tu, khanb kalapna khol/

Jamman vaali bhoeen vi, aj hoi pardes

Jithay khaidi guddyaaN, ohee begaana des

MuR muR pooraN poorney, likh saanjha Punjab

Langrial geraaN hay, zilla paway Gujrat

(I recall Lahore and my heart sinks/My soul has arrived there before I could gather my body/The place where I was born is not mine anymore/Where I played with my dolls has become a foreign land/I am repeating and writing word "Undivided Punjab" line after line/I belong to village Langrial and my district is Gujrat.)

Female Punjabi poetic scene was about to flourish when Punjab got bloodied and partitioned. It eventually took off with an epitaph to Waris Shah composed by the ever-lamenting daughter of Gujranwala. Let’s conclude this piece in pain and in the memory of those (to be) poets of the Punjab who were separated, erased and annihilated before they could even write a verse:

Dharti tey laho varhya, qabraan payyãn cho

Preet diyan shahzãdiãn, ajj vich mazãraan ro

(Blood upon the earth has even seeped into graves/Love’s princesses cry today in their mausoleums).