Dr Rohit De is a young and credible historian. Trained at Princeton University, he is currently teaching at Yale University. Now that his wife is pursuing her PhD at the Cambridge University, he divides his time between Yale and Cambridge. While in Cambridge, he is a frequent visitor to the Centre of South Asian Studies. It is here that I interact with him occasionally on various issues of mutual interest.

In one of our discussions on Pakistan’s history and politics came up the issue of language and its role in determining the intellectual trajectory of any nation/community. Rohit’s concern about the decline in the bilingual intellectual tradition in India drew my attention to the state of uni-lingualism that has steadily crept in Pakistan’s intellectual tradition over the last few decades. The gradual demise of bi-lingualism besets both countries but the situation obtaining in Pakistan is somewhat different.

Ramachandra Guha in his essay ‘The Rise and Fall of the Bilingual Intellectual’ which appeared in the Economic and Political Weekly has traced the genealogy of multilingualism having been substituted by the overriding supremacy of English language. That happened despite Gandhi’s exhortation to the Indians to adopt vernacular as a medium of intellectual exchange. Gandhi’s advice was not taken but, from 1920 to 1970, the multilingual tradition remained well-entrenched in the Indian intellectual tradition.

Guha notes in his essay, "Between 1920s and 1970s, the intellectual universe in India was -- to coin a word -- ‘linguidextrous’. With few exceptions, the major political thinkers, scholars and creative writers -- and many of the minor ones too -- thought and acted and wrote with equal facility in English and at least one other language." However, things started looking awry and the lingual plurality started giving space to English. Thus multilingual ethos has been shoved to a few pockets where it is fighting for its survival.

To elucidate the point, I cite Guha yet again, "The intellectual and creative world in India is increasingly becoming polarized -- between those who think and act and write in English alone, and those who think and write and act in their mother tongue alone." Ironically, in Pakistan, the intellectual activity performed in the mother tongue (the regional languages) is considered antithetical to the interests of the state. Thus the ‘bilingual’ in Pakistan’s case means Urdu and English.

The intellectual scene in Pakistan is currently divided quite tangibly between Urdu and English, with regional languages languishing in utter marginality. Like India, the bilingual tradition persisted until the 1970s. Vernaculars though were conspicuously absent from the educational curriculum. These languages had informal existence in homes and public sphere.

Till the early decades of the 20th century, children were given informal instruction of Arabic and Persian at home but one of the classical oriental languages was mandatory at school. Such intellectual engagement with more than one language resulted in cultural enrichment and also helped opening up newer creative avenues.

Talking about Punjabi, one must commend Najm Hosain Syed who has kept the flame of Punjabi language and literature burning. Najm too is bilingual and so were Shafqat Tanvir Mirza and Mushtaq Soofi. These scholars are a rare breed now.

Curiously enough, the pre-partition generation of the Pakistani intellectuals had the privilege of expressing themselves in more than one language. Majority of them were well-versed in Urdu, English, Persian and also Arabic and could write in the first three languages. Laureates like Zafar Ali Khan, Chiragh Hasan Hasrat, Faiz and Noon Meem Rashid could express themselves in more than one language. Before them Iqbal himself used three languages for expressing his thoughts and poetry. Among my own senior colleagues and friends, Gilani Kamran, Razi Abedi and Sajjad Haider Malik carried on the tradition of bilingualism.

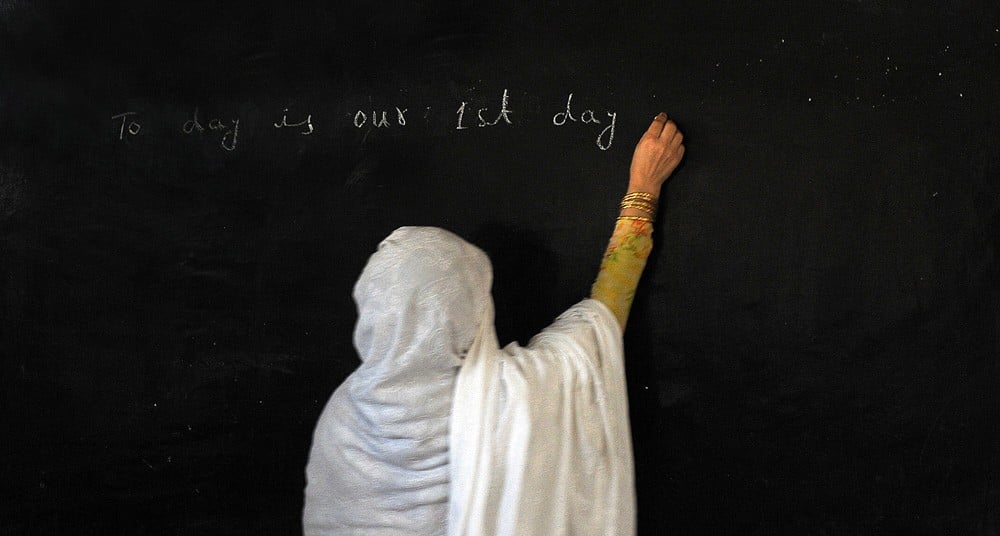

Now that tradition is a saga of the past. For the last quarter of a century, the state of Pakistan has relinquished its responsibility to educate its people. The education system in the public sector has virtually crumbled and been replaced by a mushrooming private sector. These private sector institutions tend to cater to the needs of a free market where English is perceived as a vital instrument of empowerment. Thus, cultural development ceases to be the agenda of the education system which is in place in Pakistan. Those who can afford send their children to private (English medium) schools while those with meager resources are forced to be content with public sector Urdu medium education.

Thus, the English-Urdu divide has become tangible. On top of that, Urdu is the medium of instruction in madrassas where the socially and economically marginalised are sent to study. Hence, class question becomes even more pertinent when it comes to education. Two different classes with absolutely divergent intellectual traditions and world views which are mutually exclusive are being churned out. The privileged read, act and think in English, and the under-privileged do all that in Urdu because both languages represent different thinking patterns and epistemologies.

Despite Urdu being highlighted as state’s official language and an emblem of Pakistani nationalism, Pakistani middle classes seem to be aware of Urdu’s inadequacy to guarantee a rewarding future for their children. English is the only option for them. Now that higher education has been privatised as well, the polarisation is likely to drive a social wedge alienating the rich from the poor and vice versa.

In such a scenario, the ball is in the court of the state which must bridge the yawning gap within the education systems prevailing in Pakistan. Otherwise, social anarchy is a foregone conclusion. The same holds true for India too.