Was Iqbal’s dream for the Muslims of India within a united India and in co-existence with other communities?

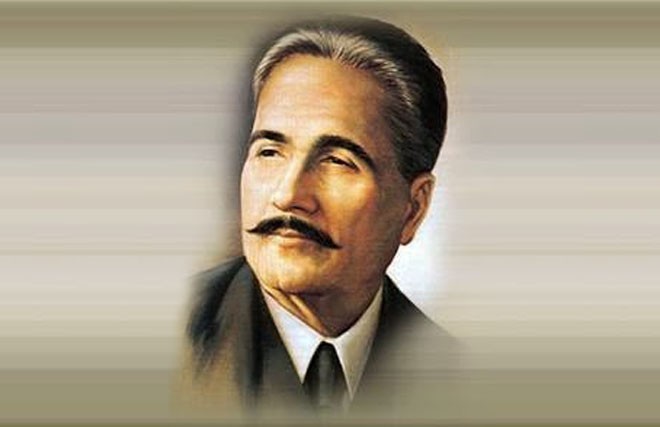

"I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single State. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North-West India." These few lines are for millions of people in Pakistan about the birth of the ‘idea’ of Pakistan. Scores of books in Pakistan quote this from Sir Muhammad Iqbal’s presidential address at the 25th Session of the All India Muslim League in Allahbad on December 29, 1930 to exhibit the genesis of the idea of Pakistan--known as Iqbal’s ‘khawab’ (dream) in Pakistan today.

So when I quoted the above speech to a Pakistan Studies class of over a hundred strong, the students must have expected the usual narration with the sole criticism fathomable being that Iqbal did not mention the north-east (Bengal) where Muslims were in a majority too. Had I done the above, the story of the idea of Pakistan would have remained the same for them and they would have been satisfied that what they had been taught and believed earlier was the ‘real truth’ (if there is a thing like that), and we would have moved on.

However, on that fateful day, I decided to shake them up a bit and pulled up on a projector screen the full speech of Iqbal. Interestingly, not even one student had even ventured to read the full speech ever--surprising since its central importance in the Pakistan narrative. The resultant discussion continued for more than an hour with most students being visibly shaken and agitated.

I began by describing the premise of the address. I asked them how many people they imagined at the session: some said a hundred thousand, other millions, and some very cautious students expected a few thousand at least. Therefore, everyone was shocked to hear the reality that when Sir Muhammad Iqbal stood up to address the session there were not even 75 members of the All India Muslim League present. In fact, poet Hafiz Jalandhri was asked to read his famous poem, Shahnama-i-Islam, to, in the words of eminent scholar Khalid Bin Sayeed "keep those who were present entertained while organisers were busy enrolling new members in the town."

At the next session of the League in 1931 at Delhi the turnout was again dismal despite the fact that the session was taking place in the capital of the country and that a sizeable percentage of the city itself was Muslim. The Hindustan Times noted of the 1931 session that it was "a languid and attenuated House of scarcely 120 people in all." By this time the League, which by 1927 only had 1330 members throughout India, was so worried about not even meeting the quorum that it lowered the annual subscription fee from Rs6 to Rs1 and abolished the five rupees admission fee in order to attract more members. Such, therefore, was the League Sir Muhammad Iqbal, undoubtedly the most celebrated Muslim poet-philosopher of India, addressed in December 1930.

As we began analysing Iqbal’s speech paragraph by paragraph his ideas became clearer and the students achieved a better picture of what he actually wanted to say. Iqbal begins his speech by describing the creation of a Muslim polity in India, and then makes a distinction between what had been happening to Christianity in the West and what will/could happen to Muslims in India. He notes that cannot be denied that Islam, regarded as an ethical ideal plus a certain kind of polity…has been the chief formative factor in the life-history of the Muslims of India." He further notes that he has despaired of Islam as a living force for freeing the outlook of man from its geographical limitations, who believes that religion is a power of the utmost importance in the life of individuals as well as States, and finally who believes that Islam is itself Destiny and will not suffer a destiny."

Iqbal then goes on to talk about the relationship between Islam and Nationalism and how the "religious ideal of Islam" is "organically related to the social order which it has created." He therefore rejects the duality between Church and State created in the West and argues that due to the different natures of Islam and Christianity, such a distinction is simply not possible within the Islamic polity.

So what about the Muslim polity (or nation) which exists in India? Here Iqbal opines that "The unity of an Indian nation, therefore, must be sought not in the negation, but in the mutual harmony and cooperation, of the many." Iqbal emphasises that it is in the harmonious co-existence of different polities or nations on which the fate of India as well as of Asia really depends."

Iqbal then carefully redefines the "higher" meaning of communalism and asserts that the right interpretation of communalism--love of one’s own community and its culture--is essential for the unity of a heterogeneous country. He notes "There are communalisms and communalisms. A community which is inspired by feelings of ill-will towards other communities is low and ignoble. I entertain the highest respect for the customs, laws, religious and social institutions of other communities." Therefore Iqbal’s ‘Muslim communalism’ means love for its own religion and culture, but without detriment to or in conflict with other communities.

It is the existence of different communal groups in India, which Iqbal argues, makes the wholesale adoption of Western democracy unsuitable for India and that in order to safeguard the interests of the Muslim community. "The Muslim demand for the creation of a Muslim India within India is, therefore, perfectly justified."

It is then within this context that Iqbal argues for the amalgamation of the Muslim majority provinces of North Western India into a new ‘Muslim India’. The creation of this Muslim India, Iqbal asserts, will be of no threat to India but will in fact "intensify their sense of responsibility and deepen their patriotic feeling." Iqbal’s dream for the Muslims of India was certainly within a united India and in co-existence with other communities.

In order to assuage fears that this ‘Muslim India’ might be religious rule, Iqbal clarifies that this will certainly not be the case since Islam has no ‘Church’ per se, and even sees the establishment of a Muslim India as opportunity’ for Indian Islam ‘ to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian Imperialism was forced to give it…’ Thus, the creation of a Muslim India would not only be advantageous for the country, but also for the community itself. In a later letter to Professor Thompson of the University of Oxford, he goes even further and lauds the Turkish experiment of the separation of religion and state and writes, "The structure of Islam permits the view that Turks have taken in accentuating separation of church and State. For this separation has meant separation of functions, not of ideas."

In sum, Iqbal argues that, "Thus it is clear that in view of India’s infinite variety in climates, races, languages, creeds and social systems, the creation of autonomous States, based on the unity of language, race, history, religion and identity of economic interests, is the only possible way to secure a stable constitutional structure in India." This is the view he presents in his December 1930 speech at Allahabad.

It is sad that while we laud the poet-philosopher and offer flowers at his grave every year on his birth and death anniversaries, we erroneously ascribe the "dream" of a separate country for Indian Muslims to him. As I explained to my students, Iqbal might have ‘inspired’ the idea of the Pakistan, but he certainly did not ‘originate’ or ‘dream’ of it. In fact, Iqbal clearly distanced himself from any scheme which called for a Muslim India outside India, and especially the ‘Pakistan’ scheme which Chaudhary Rehmat Ali and his friends had launched in 1933.

In a letter to The Times in October 1931, and then again in a letter to Professor Thompson in March 1934, Iqbal makes plain his scheme for Indian Muslims, which clearly did not envisage a separate Indian Muslim country in South Asia. Iqbal explains to Professor Thompson: "You call me a protagonist of the scheme called Pakistan. Now, Pakistan is not my scheme. The one I suggested in my address is the creation of a Muslim province, i.e. a province having an overwhelming Muslim population in the North-West of India. This new province will be, according to my scheme, a part of the proposed Indian federation. Pakistan scheme proposes a separate dominion. This scheme originated in Cambridge, the authors of the scheme believe that other Muslim roundtablists have sacrificed the Muslim nation on the order of Hindu or the so-called ‘Indian nationalism’." Nothing more needs to be said about what Iqbal said and meant.