A freedom fighter, a statesman, a prolific writer, a journalist, an educationist and a rights activist, Khan Abdul Samad Khan Shaheed sacrificed his life for a cause that benefitted the generations to come

The five-year-old Mahmood Khan Achakzai called out in alarm to his mother when he saw a man enter his house in Inayatullah Karaz in Gulistan, about 70 km from Quetta. The man was none other than his father, Khan Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai, who was released from prison in 1953, five years after the birth of Mahmood Khan Achakzai.

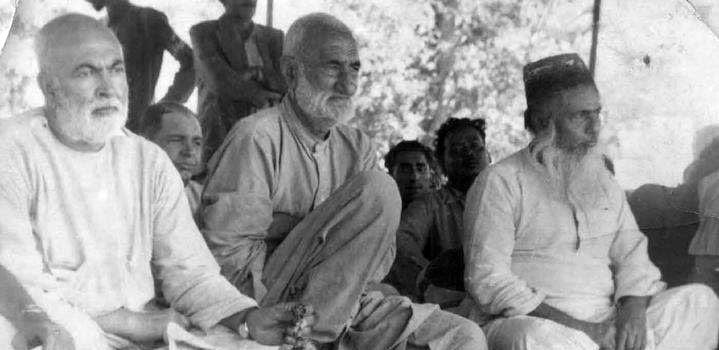

Samad Khan was a versatile personality: a freedom fighter, a statesman, a prolific writer, a journalist, an educationist and a rights activist. Samad Khan was the first Pakhtun nationalist leader of the 20th century who was not only conscious of the political rights of the Pakhtuns but was also aware of the importance of the geographical unification of Pakhtuns on this side of the Durand Line.

Khan Abdul Samad Khan (Shaheed) was born in July 1907 in a village near Afghanistan’s border, Inayatullah Karaz, Gulistan tehsil, District Killa Abdullah, in the region named by the colonial power as British Balochistan. He received his primary education in his village madrassa. As a student of class eight, Khan led a procession of school boys in support of the Khilafat Movement. He was expelled from school for such a daring act against the British empire in the sensitive border areas.

However, the turning point was the visit of the Afghan King, Ghazi Amanullah Khan, to the Chaman area, then part of the British Balochistan. The young Khan was present on the occasion and witnessing the English soldiers asking the local Pakhtun sepoys to wipe their shoes with their clothes after the guard of honour was presented to the king. Thereupon, Khan decided to formally become part of the independence movement of the subcontinent.

Khan Abdul Samad Khan was arrested for the first time in May 1930 for his political struggle against the colonial British rule. Prior to the arrest, he had been served two warnings by the colonial authorities for his involvement in political activities. The first interrogation followed by warning by the colonial authorities was against his initiative of translating the Holy Quran into Pakhtu for villagers who came to the local mosque attended by Samad Khan as a young man.

He was struggling to organise a political movement but could not succeed before May 30, 1938 when he founded the Anjuman-i-Watan. In 1954, he founded ‘Rora Pakhtun’ movement. Later he merged his movement into the National Awami Party (NAP). Khan separated from the NAP in the aftermath of incorporation of Pakhtun’s belt in the current Balochistan province in the Constitution of 1973.

The struggle for independence, democracy and equal constitutional rights for his people resulted in his spending more than half of his adult life in various prisons of British India and Pakistan. And as a reward for his struggle, apart from multiple house arrests, he was imprisoned from 1930 to 1947 by the British and from 1947 to 1973 after independence. He was arrested on the second day of Ayub’s martial law and was released after his downfall.

He completed his education, from middle to graduation, in prison and taught his illiterate jail mates. During his years in jail, he penned Tafseer and translated various books -- ‘The future of freedom’ into Urdu and Maulana Shibli Naumani’s Seerat-un-Nabi into Pakhtu. Khan also authored a biography "Zama Jowand Aw Jowandun’ (the way of my life) in three volumes.

He also introduced Pakhtu script by omitting alphabets of other languages that Pakhtuns could not pronounce. He was a great advocate of imparting education, at least up to the primary level, in mother tongue. Based on his personal teaching experience in prison, he claimed that an illiterate can learn and write in six months if imparted education in his/her mother tongue.

This great leader published the first newspaper ‘Istiqlal’ in January 1938 from Quetta. He struggled for seven years, even at time of his imprisonment, through political mobilisation and writing to the colonial authorities to extend the ‘The Indian Press Act’ to Balochistan. Besides his political struggle for independence, being editor of Istiqlal, Khan raised voice for press freedom from the platform of ‘All India Editors Conference’.

He spent the last four years of his life (1969-1973), the longest spell in his political life out of prison, struggling for universal franchise, one-man one-vote in Balochistan and the tribal areas where only members of official Jirga were entitled to vote. During this period, he contested the election of 1970 and was elected as the member of first Provincial Assembly of Balochistan and presided its first session to take oath from the elected members.

Khan’s political thinking and stance on national, regional and international political issues reflects his far sightedness, political acumen and statesmanship. Today, his vision and stance about international relations and foreign policy stand vindicated. He predicted that becoming part of SEATO can only benefit the Western block and will destabilise the region by antagonising another superpower, the then Soviet Union. He considered such alliances as a threat to international peace and stability.

Khan opposed a foreign policy, particularly toward neighbours, based on hatred and hostility rather peaceful co-existence. He believed that without political independence, genuine democracy and equal citizen rights, economic independence and prosperity that characterized a welfare state is a far cry.

He was also conscious of urban rural development disparity. In late 1960s, he sensed that the concentration of development projects, job opportunities and social services in urban areas at the cost of rural was leading to uneven development that will consequently shift the demographic pressure to the cities. The great Khan was considering a just and transparent tax system, capable of netting the taxable to avoid indirect taxation which ultimately affects the poor.

Being himself a grower, Khan was also mindful of introducing scientific and new techniques in agriculture and emphasised on the government’s support and assistance, particularly for small farmers.

He was a great advocate of labour rights. He wanted labour rights like fix time and adequate wages for rural, including agriculture, labourers.

This visionary leader, hailing from a tribal region, was staunch advocate of women rights. He challenged the tribal taboos by campaigning for registration of women voters before the first general election based on universal suffrage in 1970. During his campaign, Khan forcefully argued that women votes carry equal importance and weight.

He set personal example in the tribal environment by educating all his children, sons as well as daughters. In the absence of transport, he encouraged his daughters to ride a bicycle to school in Gulistan.

He considered tribalism and tribal chiefs as retrogressive tool in the hand of bureaucracy to suppress and keep people backward. Khan also struggled against the black law of the Frontier Crime Reglation (FCR).

Khan was the only nationalist politician sitting in opposition in Balochistan Assembly until he was martyred. This icon of independence, a champion of constitutionalism, democracy, rights and a torchbearer of peace was assassinated in his Quetta residence on December 2, 1973 by an unknown assassin who threw a grenade in his bedroom via a ventilator.

The great Khan sacrificed his present for the future generations. However, his political legacy of struggle will continuously illuminate the horizon of oppressed nations.

Today, Khan Abdul Samad Khan Shaheed stands tall as the world relishes independence, democracy and peace more than ever which makes him victorious in the annals of history.