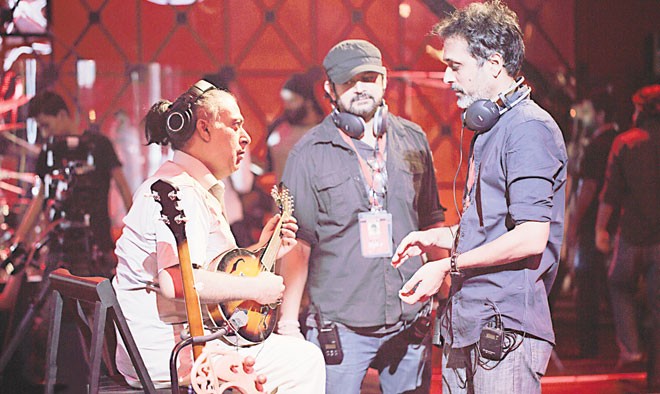

Season Seven, produced by Strings, saw a change in the show's philosophy but then it had to create a new legacy instead of continuing Rohail Hyatt's standing one.

The seventh season of the super-hit Pakistani music show Coke Studio marked the beginning of a new era for this iconic program. After six seasons of being produced by the man most readily associated with the show – Rohail Hyatt – this season marked a new pair at the helm. Bilal Maqsood and Faisal Kapadia, more famously known from the veteran pop band Strings, were the producers for this edition.

While there were many overt similarities between this season and those that came before, this year’s Coke Studio had many fundamental changes in it. In order to be able to appreciate these, it would help to get a sense of why Rohail Hyatt conceived of this show, and how it evolved over time.

When Strings were first announced as the producers of Season Seven, the news was largely received very positively. The last two seasons of Coke Studio had come under increasing criticism and clamour for change, and this reaction seemed to reflect an increasing distance between the intentions of the show, and the popular perception of it.

For many people, Coke Studio had come to represent a television show about music. Consequently, audiences wanted hit songs, famous guests and renditions of solid-gold classics. It was also (loudly) claimed by many that the show’s music was too predictable and had become formulaic, with people particularly criticizing the constant fusion with devotional music.

Yet while the hits and the fame were happy by-products of the show’s development, it was intended for something quite different. At the start of Season Four, Rohail Hyatt explained in an interview how he had first come to develop the show.

"I personally ventured onto classical music by myself. Perhaps discovered it about a year before Coke Studio, and I was pretty blown away by the fact that here I was, a musician all my life, and I had no idea about a treasure of an art form that we had such little knowledge about and it was so different from the western music that we had grown up with."

The show was developed as a way to showcase this vast cache of music and make it culturally relevant to Pakistani society again. After an experimental first season, where the team went in several directions, the duet between Ali Zafar and Saeein Tufail was what provided a creative breakthrough. In Rohail’s own words "The first season was different – you can tell the concept of fusion was there, but it was limited to something like a dholak in every song. The real experimentation was with ‘Allah Hu’ by Saieen Tufail and Ali Zafar, because I had put that out there as a test reaction … It was a very mesmerising moment when Ali Zafar finished that song – there was a pause, and then the audience started clapping, and they just wouldn’t stop. And I instantly knew ‘yaar this tune has connected.’ It gave us all the confidence and encouragement to move on to the next season."

One of the most central tenets of the production process was to set each song to the architecture of eastern classical music. Rohail called this the ‘entire engine’ of the show, and claimed it was the main reason people were resonating with the music so much.

The entire idea was to make the traditional and organic music of this region relevant again and this was one reason why there were so many cross-genre collaborations, as more popular pop stars performed together with classical and folk musicians. By season five, this evolution had firmly established its own internal logic, one reason that less discerning audiences began to feel repetition. Safieh Shah, a music critic who wrote extensively on the show, said at the time that "the question isn’t why does Coke Studio sound the same – the question becomes what is this sound that Coke Studio is making? With each of the songs in this episode, you begin to realise that this familiarity is the architecture of a Coke Studio song – an architecture that pervades not just individual songs, but the whole oeuvre of this program."

Season Six, the most delayed and ambitious of the Rohail Hyatt era saw the show travel internationally, collaborating with musicians from a wide range of countries and cultures. For many, this came across as terribly indulgent and wasteful. Few noted the ramifications of what this change meant, articulated here by Safieh Shah.

"This season represents a seismic shift in the flow of cultural influences, with external musicians internalizing ours (musical sensibilities), which can clearly be seen as the focus of the behind the scenes (BTS) of every production thus far this season. This may not seem momentous but musically things have indeed come full circle with Coke Studio, so instead of us trying to find ourselves through other cultural influences, we now have an identity that others turn to when seeking themselves."

So this was where the show found itself when the big changes came. The start of Season Seven immediately made clear the extent of the new start – along with Rohail, a large part of the house band had also left. Initial press releases and interviews also reflected a desire to incorporate more of Pakistan’s oft-forgotten film music, which was a genuinely exciting idea.

The songs also showed a change in philosophy. For starters, the ubiquitous synth-based start to each song – which was the direct link to the eastern architecture – was replaced by more pop or rock-styled openings, often beginning with a piano solo. The band also incorporated an orchestral section, which was prominent in many songs. The season also saw an end to cross-genre fusions, with almost all the collaborations involving artists from similar musical backgrounds and styles. Most noticeably, the covers for most songs were largely similar to their original compositions. While previous seasons would often deconstruct songs to the point of not being recognisable anymore, the covers in Season Seven stayed far more faithful.

In terms of the playcounts, the biggest hit of the season was Sajjad Ali’s ‘Tum Naraz Ho’, whose playcount on Soundcloud (the most common platform for listening to the show online after the banning of Youtube) was well over twice the numbers for its closest rivals. It was also a fitting representation of the season, comfortably familiar to the original and sung by a big star.

Yet the two artists after Sajjad on the playcounts were both young musicians who were the breakout stars for the season. Asrar’s ‘Sab Akho Ali Ali’ was perhaps the most critically acclaimed song of the season, and represented the continuing appeal of fusing devotional music with contemporary sounds. The other big success was Jimmy Khan, whose pop-infused love songs were almost equally popular. The two artists also showed two divergent possibilities for the show – Asrar’s songs were largely the continuation of the devotional fusion the show had come to be known for, while the fusion of Jimmy Khan’s ‘Nadiya’ with ‘Gaari Ko Chala Babu’ (from the 1956 film, Anokhi) pointed towards shifting the focus towards our film music tradition. Unfortunately, neither stream was pursued more often across the season, and perhaps could serve as a template for the next season.

Personally, there were several songs in this season that continued the show’s tradition of producing some understated gems. Sajjad Ali’s ‘Suth Gana’ was an immensely enjoyable composition, embracing the joy and vitality of the song’s lyrics. Usman Riaz’s ‘Descent to the Ocean’ was another brilliant track, capturing the spectrum of his prodigal talent. The Niazi Brothers’ rendition of ‘Lai Beqadran Yaari’ was also extremely enjoyable, and its triumph was the lovely mandolin melody played by Ustad Tanveer. Indeed, he was the standout addition to the houseband this year, with his various percussive pieces adding enjoyable layers to several songs.

For the producers, one has to conclude that this has been a bracing season. After all the hype that is inevitably associated with Coke Studio, they were suddenly expected to answer everyone’s demands. While there was much already to build upon, there is a sense that Strings have yet to fully impose their own vision on the show. Given that Season One was where Rohail and his team were mostly finding their own sound, the same leeway must be given here as well. But what is important going forward is that there is an impeccable and unwavering commitment to an idea of what this show means. That should be the basis for the creative avenues the show explores in the future, and can be a way for it to be reinvented.

That said, there is also something to be said about music ‘fans’ and ‘critics’ across the country. Reading reviews and reactions to the final episode, there was a palpable sense of disappointment from people who had expected lots of different things. Perhaps because Coke Studio was seen as a TV show (rather than successive music albums that were recorded on video) there was a demand for the cast to change, without an appreciation of the impact of such changes. Indeed, the last two seasons had become the focus of misdirected outrage, and the limitations of Season Seven reminded many people of the quality of what they once had. Unfortunately, like with most things in Pakistan, we only came to appreciate this once it was too late.