Revolutions never work from the point of view of humanist values and human rights. Now that young Pakistanis are talking of revolution, it is imperative to remind them that they should talk of strengthening institutions and not a leader however promising

Though associated with the left since the middle of the nineteenth century in Europe, revolution is now also a slogan of the religious right. While the wall-chalkings in South Asia proclaimed ‘Asia surkh hai’ (Asia is Red) in the 1960s, the more catchy slogan now is ‘Islamic Revolution’ at least in Pakistan.

Indeed, the status-quo oriented, well to do youth of the Pakistani educated elite also calls itself revolutionary nowadays without, however, confronting the thorny question of their own status if a revolution actually came about.

It is easy to understand where the appeal of revolution comes from -- from the so much corruption, cruelty, mismanagement and sheer misery in the world.

The trouble is that in practice revolutions bring misery to even more people than the corrupt old system. They are generally cruel in the extreme. Revolutionary leaders do not consider themselves subservient to the rule of law and feel so persecuted by enemies, real and imagined, that they let loose a reign of terror killing millions of people for dubious gains.

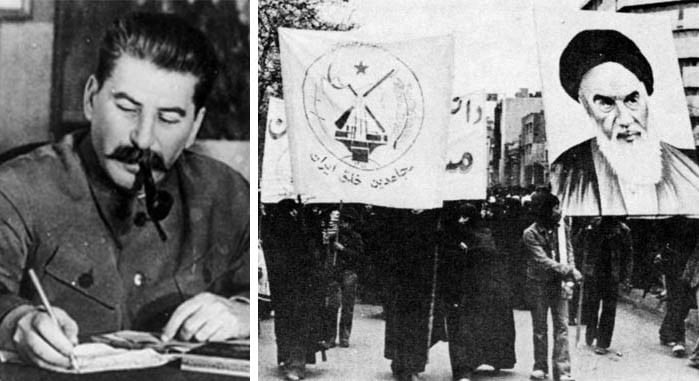

They also bring about real progress in certain domains but the cost at which it is achieved is so terrible, so mind-bogglingly bloody, that it’s a wonder anyone should praise or desire a revolution. I can give many examples from the reign of terror following the French Revolution (1789-1799), the Cultural Revolution of China (1966-76), the dictatorship in North Korea etc. The list is long but I will confine myself to two examples: Stalin’s rule following the Russian Revolution and the Iranian Revolution.

I will focus on two books about both: first, Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Stalin: the Court of the Red Tsar (2003) and the other Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003).

The first is a voluminous book in 720 pages even without the huge bibliography which runs into many more pages. It is a book of history written by a painstaking researcher who has delved deep into the Russian archives and other relevant historical sources. It is written in a lucid, dramatic style which makes for riveting reading but 672 pages in small print would tax anybody’s patience. I, for one, enjoyed it as if it were a novel -- a novel of the macabre! The central character of this Russian tragedy is Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (1878-1953).

The second autocrat of the Soviet Union, like his predecessor Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), had no time for something as ‘bourgeois’ as the rule of law or democratic institutions. Lenin had established the Cheka, an organisation meant to ensure censorship and punish supposed enemies without a proper trial, which sent at least 70,000 people to labour camps by 1921. Stalin went further establishing about 500 Gulags and sending millions to labour and death. Lenin had created famines and dislocation by his policies but Stalin created a genocide. His policy of forcing farmers (Kulaks) to work in collective farms or work as labourers in factories created appalling starvation for them.

The book gives conversations and letters as evidence that Stalin did not want even to hear of the miseries and starvation of the kulaks and so they died like flies. Incidentally, the same thing happened in Mao’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ in China in the late 1950s.

In all cases these autocratic leaders had one obsession--how to force-march their countries from being backward agricultural countries into modern, industrial powers. All of them succeeded but the human cost is so appalling that no sane person will agree that such methods should be used anywhere.

When there is no due process and no institutions to ensure the rule of law, one man’s word decides the fate of millions. His closest comrades are at tremendous risk because powerful people, unchecked by any institution or subject to replacement by elections, become cruel and often suffer from jealousy of others and paranoia.

The turning of Stalin into a monster is described in fine detail. His reliance on Beria, his trusted executioner, is much blamed for some of his atrocities; yet the book makes it clear that Stalin knew that people were imprisoned, made to write false confessions under torture and then killed ruthlessly. Even generals of the army were given this treatment till people feared their own shadow. Yet for those who romanticise revolutions there is the scene of members of the Politburo going in and out of each others’ flats in the Kremlin and Stalin’s wife Nadya writing to him for 50 roubles.

But this Bolshevik simplicity was short-lived. In due course, Stalin and the others lived in dachas and lacked for nothing. Some, like Beria, preyed upon girls whom he simply got lifted out from the streets while for others the intoxication of power and sadism was enough. The chapters of the book dealing with the witch-hunt of the comrades of the Communist Party itself -- ‘The Executioner: Beria’s poison and Bukharin’s dosage’--are a difficult read. It is not the language or the concepts which are difficult, however; it is the despair one finds oneself sinking into by this manifestation of human cruelty and depravity.

And one is surprised at the way the war (World War II) was mismanaged. First, Stalin would not believe Hitler would attack Russia. And secondly, when he did, Stalin interfered with the generals in his bid to keep control or because he had such delusions of grandeur that he thought he knew best about everything including warfare. The Russians won because the winter was on their side and Hitler was just as mistake-prone and dictatorial as Stalin.

And yet, after all these years, some people still believe in Stalin’s greatness. Vladimir Alliluyev, whose parents were destroyed by Stalin’s orders, still believes he was a great man with some bad aspects to his character. Human beings are so impressed by power, even by destruction, that they hero-worship monsters. History is full of it.

The other book Reading Lolita in Tehran is not such a detailed book at all. Nor is it so studded with references and proofs. It is the personal account of Dr Azar Nafisi, a university professor of English literature, at the University of Tehran. It is partly like a memoir in so far as she talks of Tehran during the years of the revolution (1978-1981). But it is not a straight biographical account since major portions of the book deal with the classics of literature in English -- Jane Austen, Nabakov, Scott Fitzgerald -- which serve as metaphors about Iranian society. But such symbolic devices can only be appreciated by those who understand the functioning of literary texts.

Why then is the novel so moving?

Not because there are no histories and journalistic accounts of the Iranian revolution. There are many. But one reason of the power of the book lies in the way Nafisi just wants to go on teaching literature. She even arranges a class of girls in her own house. They want to get away from the revolution which prevents them from pursuing their lives. Nafisi cannot teach in the university since she refuses to wear the head scarf and others are imprisoned for their beliefs. The book is about the impossibility of living an ordinary life in a revolutionary country where young men roam around as vigilante groups to curb freedom of expression and ideas. But Iran is much better than Stalin’s Russia since Nafisi leaves for the United States in 1997 so the comparison with Stalinism would be invidious.

The major point is that revolutions, no matter what their ideology or justification, are oppressive. They give excessive powers to their leaders who generally turn cruel since there are no institutions to stop them. These leaders may well bring about great changes for the better in some fields -- like industrialisation of Russia and China or the increase of the GDP in Hitler’s Germany -- but it is at an appalling human cost.

This point is captured hauntingly by George Orwell’s novel Animal Farm which makes the point that revolutionary leaders become like the tyrants they replace through violence. Revolutions never work, not from the point of view of humanist values and human rights.

Now that young Pakistanis are talking of revolution, it is imperative to remind them that they should talk of strengthening institutions and not a leader however promising. They should adhere to the norms of democracy and wait for its slow evolutionary processes to weed out the evils they hate and not opt for the revolutionary path of vigilantism.

Not heroes and leaders but institutions; not revolution but evolution; not bloodshed but tolerance; not purges but trial by law and due process -- this is the best way for Pakistan.