The changes proposed by the JI will add more details about Islam, ideology and nationalism in textbooks taught in KP

Back in 2004, when Pervez Musharraf ruled, the senior minister of the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) in the then North West Frontier Province (NWFP) assembly, Sirajul Haq, warned the federal government that students of the province were united against the intended changes that were to be made in the syllabi. He stressed that if the students didn’t want to read a textbook that has been modified by the federal government, no power in the world could compel them to do so.

The minister hadadded in the same breath that the federal government should come up with a curriculum, which had the potential to produce good Muslims, besides churning out good doctors and engineers.

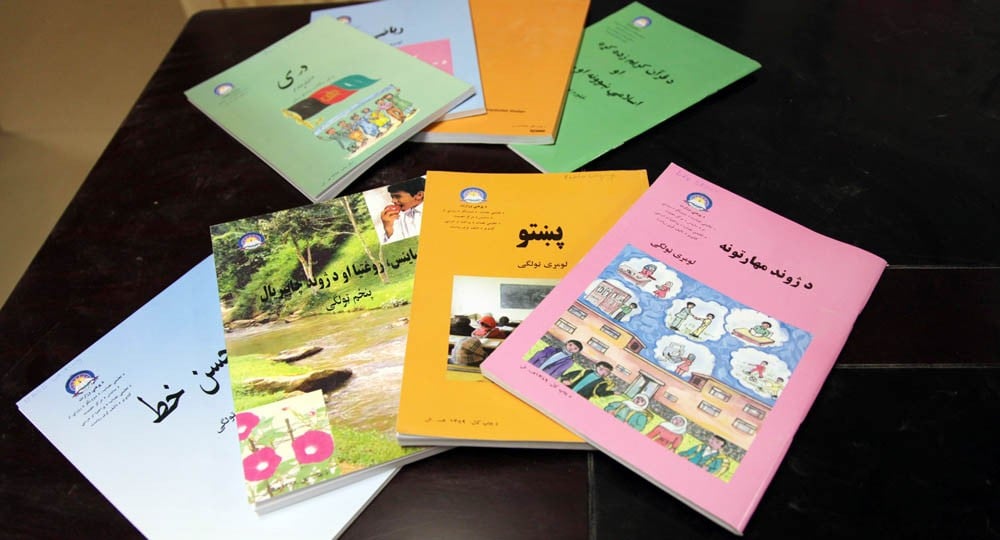

Come 2014 and the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) led provincial government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa succumbed to the regressive demands of its coalition partner Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) to revert to the curriculum in public sector educational institutes set in 2004. The cognitive educational specialists view this as a move to poison the minds of next generation.

The gradual change of syllabus in educational institutes started with the educational reform committee in 2006, which called on experts in education from all over Pakistan to come up with recommendations that would put the students of this country at par with the rest of the world. Back then the religious parties conglomerate MMA was ruling the province and it failed miserably to come up with even a single recommendation to standardise the curriculum.

Unfortunately, the misguided approach of the past is being replicated in the present by the self-proclaimed torchbearers of change.

The passage of the 18th Amendment in 2010 transferred the power to run educational affairs to all provincial governments of Pakistan. The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government, alongside the Punjab government, started implementing the recommendations made by the Educational Reform Committee. In 2012, the ANP government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa introduced the reformed curriculum in schools amid hue and cry raised by the religious parties that viewed the new syllabus as secular, Godless and a work of the devil itself.

The need for changes was felt because the curriculum was thought to be regressive, where local nationalism and a particular religious mindset was imposed on a large portion of the population. This led to the demonisation of minority groups living in the country. This form of educational curriculum has disillusioned many young generations of Pakistanis in the past. Now, how would an approach that has let us down in the past do wonders in present and future?

The present educational committee has moved verses related to jihad from grade 9 to grade 12 course books, maintaining grade 9 students are not mature enough to understand the essence of jihad and a misdirected surge of testosterone might result in children falling into the wrong hands.

In order to draw a clear distinction between religion and science, the previous provincial government deleted 18 Quranic verses from the grade 9 chemistry textbook. The proposal that a new topic would soon be introduced in the Islamiyat course where science would be discussed under the Quranic teachings was also put forth. Similarly, from physics book for Grade 9 and 10, the Quranic verses and Hadiths regarding creation of the universe and the ecosystem were omitted. The education policymakers believed at the time that by doing so the non-Muslim students could study sciences without having to learn the Quranic verses.

The JI misunderstood this as a move to poison the minds of students against Islam.

Similarly, the grade 8 Pakistan Studies textbook that was reprinted by the previous provincial government carried chapters on Raja Dahir and Maharaja Ranjit Singh. But religious parties objected to this content change. Little do they know that both these personalities are revered by various communities in the country, especially in Sindh where the execution of Raja Dahir at the hands of Arab invaders is still commemorated as a day when a Sindhi ruler was martyred at the hands of a foreign military force.

In order to avoid overlapping of lessons in various course books related to the Holy Prophet (PBUH), the four Caliphs and Muhammad Ali Jinnah in the Social Studies grade 4 textbook were replaced by lessons on Khushaal Khan Khattak, Haji Sahab Tarangzai, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Sardar Abdul Rab Nishter, Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum Khan, Maulana Mufti Mahmood and Jalal Baba. Full fledge chapters on the lives of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and the caliphs were already present in the course books of Islamiyat.

Similarly chapters on Nelson Mandela, Karl Marx, Marco Polo, Ibne Batoota, Vasco da Gama and Neil Armstrong were introduced in the social studies books of grade 5. Here again, topics on Hazrat Khadija (RA), Hazrat Fatima (RA), Hazrat Imam Hussain (RA), Muhammad Bin Qasim, Mahmood Ghaznavi, Aurangzeb Alamgir, Shah Waliullah, Tipu Sultan, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Allama Iqbal and Jinnah were dropped. The changes were made to open up new topics for the students.

Dr Khadim Hussain, educationist and author of Re-thinking Education, terms the changes in curriculum proposed by the PTI-led provincial government as "Radicalisation 2.0".

Dr Hussain, who was also a member of the Educational Reform Committee says, "What these political parties perceive as objectionable material in the curriculum were topics related to the current crises that we are facing as a nation. Instead of teaching our children about war heroes of centuries past, we tried to introduce them to various contemporary movements and personalities of the last century that shaped the affairs of the present day world."

He adds that such concessions will embolden the JI to keep demanding changes until their interpretation of Islam is imposed on the people of this country.

As things are, it would not be surprising that chapters on Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and his poet son Ghani Khan in the Pashto books of grade 12 also come under scrutiny soon.

Have we not yet learnt important lessons from our past mistakes? Are we producing cannon fodder for the next jihadi project on purpose? The questions cannot be avoided any longer.