Focusing attention on the instance of bonded labour in the kilns despite a host of decisions by the superior courts against it

The brutal murder of Shahzad and Shama Masih in Chak 59 near Kot Radha Kishan is being seen as a sign of the decadence and degeneration that defines the state of our society. That indeed is a sad fact.

There are some other facts surrounding the incident, many of which are in the realm of grey and may not help any investigator in a straightforward manner. Of these, one fact stands out for its sheer clarity -- that Shahzad and Shama were locked inside a room along with their little daughter by the bhatta management because they had loaned money from the owner and he feared they would run away.

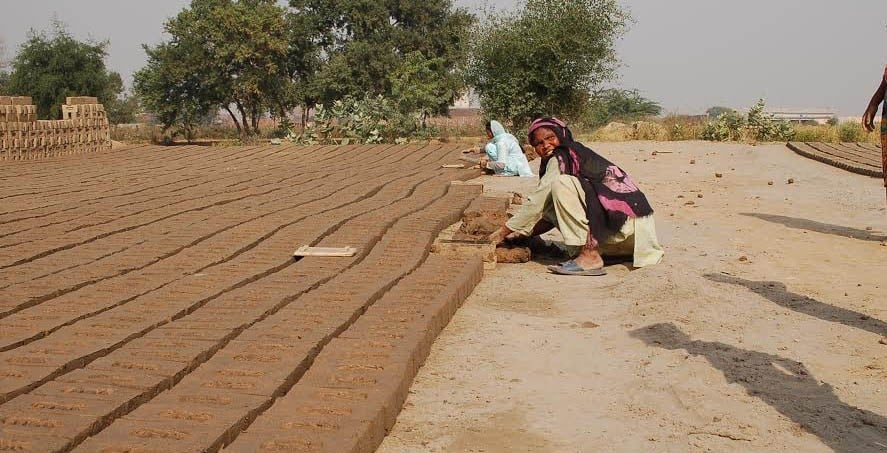

They were physically stopped from escaping from the claws of death (if not actually driven to these claws) even when five of Shahzad’s brothers and their families worked on the same kiln. This fact draws attention to the state of labour in the brick kiln industry which is said to employ about 4.5 million people all across Pakistan. The kilns in Punjab province employ many Christian households too.

We have in today’s Special Report focused attention on the instance of bonded labour in the kilns despite a host of decisions by the superior courts against it. There indeed have been measures taken by successive governments as well as the courts to not just preclude bonded labour and the potential of violence but also to institute safety nets in terms of social security.

A lot of these measures remain cosmetic since most of the industry operates in the informal sphere, where either the kilns are not registered and cannot be held accountable for or the workers are not registered to be able to benefit from the safeguards available.

Thankfully there are organisations and courts available for legal redressal which is constantly sought and provided but that happens only for isolated cases. The sector at large remains exploitative; the system of payment is such that workers are bound to stay in a bonded state, without any education and health cover for them. Even if instances of active violence have decreased compared to the 1980s, there is violence latent in bonded labour.

These and many other issues are discussed in today’s Special Report.