The young miniaturists who have come into their own during the 1990s and 2000s have no experience of colonialism; they do not exhibit any of the apologetic guilt at being artists. Many of them profess a postmodernist orientation: having recovered for themselves a buoyant confidence in relation to the archive of the world’s heritage

Even as they mediated the influence of Euro-American modernism, the artists in Pakistan had to negotiate with the more immediate pressures of the quest for a postcolonial national identity. How were they to modulate the compulsions of ideology with the dictates of imagination? How could they achieve reconciliation between their ambitions and the various syndromes of hesitancy, inferiority and prickly sensitivity that their situation as postcolonial subjects inflicted upon them?

Their peculiar cultural position exposed these artists to the charge of elitism: they remained harried by the problem of address and audience. What imagined community were they reaching out to? What intervention, if any, were they making in that arena of human interplay, the public sphere?

Such were the dilemmas which afflicted early Pakistani modernism.

The preoccupation with the quest for an indigenous aesthetic, to be constructed and expressed through the pictorial image, ensured that the first generation of postcolonial Pakistani artists remained formally conservative and thematically unadventurous. Its chosen idioms -- the iconic, even heroic single image, the mythic narrative, the national allegory -- were pure forms characterised by composure, as though in reaction to the confusions of experience.

Within two decades, these idioms had lost, for the most part, the emancipatory and transfigurative vigour of their intention. They acquired, instead, the mannered stylisation of hieratic classicism, or worse, permitted a static and picturesque Orientalism to overwhelm the fluctuations of actuality.

Such was the state in which miniature painting as a genre floundered until the early 1990s.

Propelling themselves away from the grand fictions of indigenous symbology and abstract idealism, a group of younger artists in the Department of Miniature Painting at the NCA, Lahore, asserted their desire to engage with the immediate and necessarily hybrid realities of their society while functioning within the traditional (read narrow) confines of the historical practice. Some of these dissidents, in the quest to reinvent a moribund genre entrenched in classicism, insisted on painting the local in autobiographical gestures, as a private sphere of emotion approached through subtle fables and crafty parables.

In accentuating a provisional locality -- the sense of a particular region that can nevertheless carry a freight of emotional and ideological associations which link it to the wider world - these artists expanded the space of art to include a dimension of dialogue and with its nuances of solitude, terror, nostalgia and intimacy, the recognition of the unique human presence as the first step towards the revolutionary transformation of the world, a secular redemption.

It is in the art of Shahzia Sikander that the affirmation of the human predicament reaches its most deliberate pitch. She believed that to paint the human being (with all its vulnerability, confusion and determination to survive) implies empathy and an ethical, even political, responsibility towards the subject of representation. Similarly, to paint a particular territory -- recording its transition across a period of tumultuous personal and historical change -- is to approach the landscape with participatory and loving attention rather than an exploitative conquistador ambition.

This is how, as they painted the hoi polloi, immortalising their proletarian resilience without romanticising their tragedy, the constellation of miniature artists opened up for themselves a possibility of social and political action. Along the same tangent, painters like Waseem Ahmed also arrived at a figurative idiom in which the human figure held out the gifts of surreal satire, erotic vigour or simply a riddle-like disquiet.

The young miniaturists who have come into their own during the 1990s and 2000s have no experience of colonialism; they do not exhibit any of the apologetic guilt at being artists, the anxieties of cultural identity which haunted the generations preceding theirs. Many of them profess a postmodernist orientation: having recovered for themselves a buoyant confidence in relation to the world, and to the archive of the world’s heritage, these miniaturists would have no hesitation in endorsing the new internationalism that Salman Rushdie outlines in his essay, Imaginary Homelands:

"Art is a passion of the mind. And the imagination works best when it is most free. Western writers have always felt free to be eclectic in their selection of theme, setting, form; Western visual artists have, in this century, been happily raiding the visual storehouses of Africa, Asia, the Philippines. I am sure that we must grant ourselves an equal freedom."

It is this internationalism which has enabled Pakistan’s younger generation of artists to survive and flourish in a time of upheaval. It has allowed them to tap into the ‘information state’ and subvert the cultural imperialism that the global market order has insinuated into Pakistan; it has imparted to them the dexterity and finesse required to make their way across a consumerist pattern of patronage and yet savour the possibilities of cultural renewal.

These are the instincts that equip them to carve interstitial spaces in a nation-state bedevilled by internecine power struggles, low-intensity warfare, and collapsing infrastructures.

At the same time, and as an outcome of the same processes of globalisation, the artists who constitute this generation are no longer necessarily products of the metropolis. They emerge from various centres and circulate among them: Hyderabad, Quetta, Faisalabad, Gujrat, and so forth. Recognising their cultural identity to be unstable and in flux, they are almost prodigally experimental in the formal languages they adopt. Practicing a diversity of idioms, they are markedly multi-disciplinary in propensity; often, they abandon the painterly frame altogether, to express themselves through the assemblage and installation.

As against the compositional bias of their predecessors, this generation prefers the risky procedure of improvisation, applying itself to mixed-media assemblages, graphics and installations. This choice is not without its own dangers: if the composition suffered from the innate peril of the formula, the improvisation often flattens out into the high finish of the designed image, a seductive mail-order concept gleaned from the generic glossaries that are presented through exhibition catalogues emanating from New York and Venice, Hong Kong and Kassel.

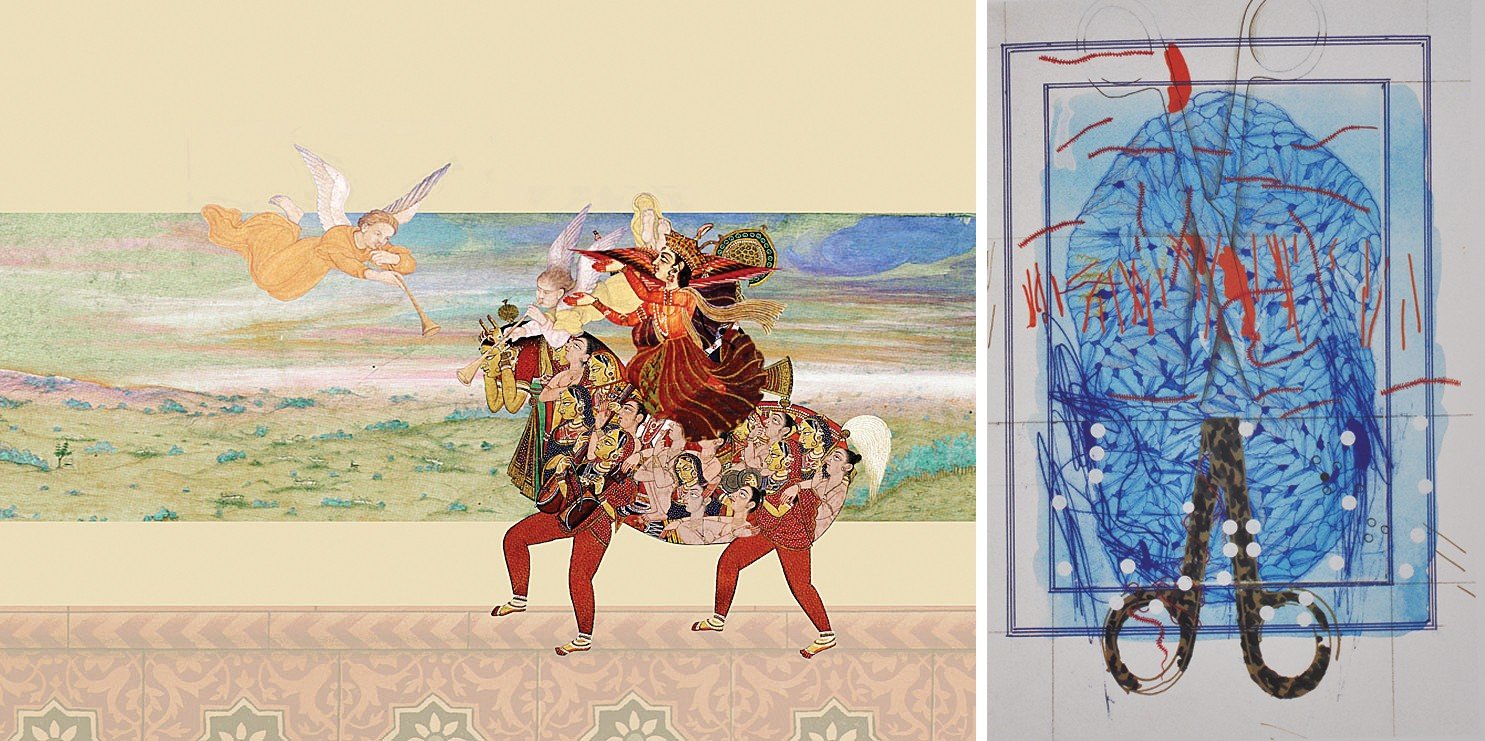

Mediating history through the exhibition space, these younger miniaturists have adopted an array of montage techniques to address contemporary experience. Bizarre as these altered conceptions of space and context may seem to viewers habituated to an earlier and more reassuring style of painting, these audacities signify a nascent aesthetic, one that must invent new modes of editing a cosmopolitan reality. In this existential jigsaw, the television image is as important an element as the quotation of the Jehangiri miniature.

These young miniaturists are united in their recovery of play as a serious principle of construction, as the first move towards the creation of a parallel reality. These artists create a space, therefore, in which argument and theatre, ritual and circus can all take place, often simultaneously. Here, they dispute received mythologies and bring contemporary mythologies into being, however fragmentary and notational they may be.

For example, Muhammad Zeeshan celebrates the quirky, the quizzical and the private meaning. He questions the ceremonial relations that bind the self to the world; the joyous fantasies of sexuality are contrasted with its fearful obsessions, in his works. The human figure is repeatedly interrogated and dismembered, translated into cybernetic form; its hopes are contained, its terrors spill over.

An anti-aesthetic impulse is most noticeable in Imran Qureshi: knocking the art work off its pedestal, he shifts the viewer’s focus from product to process. He emphasises the act of making: he reveals the stitches, scratches and marks of the maker, which encode both an artisanal roughness and a tender lyricism, while constructing and deconstructing new forms as experiments in recycling and metamorphosis.

The quiet insistence on exploring the miniature and its potential for compassing the epic is a departure from the norm. In an epoch dominated by young artists who extol the virtues of magnified scale, extend their work through massed multiples, employ platoons of assistants, and operate through an assembly-line model of production, Qureshi prefers the consolations of solitude and reflection. He plays sophisticated visual and conceptual games with his viewers, resonant with the wit and philosophical deftness of Magritte, and yet communicating the meditative quality of the Dunhuang scrolls and the Ajanta murals.

In Khadim Ali’s work, the demons are largely drawn from the representation of Asuras in the Kangra miniatures. Here, they appear as machines of caricature and calisthenics, rather than as things of blood. Their traditional role in mythology was to wreck the sacred sacrifice, and wreak havoc on figures of power and authority. The sword, an intricately decorated prop which may imply the aestheticisation of violence in popular culture, recurs in each miniature, to mow down the demons.

Sometimes, it becomes possible to see the demonisers as themselves being the demons: such reversals of perception are probed in Saira Waseem’s work. This is significant in an age when George Bush launches a brutal war of occupation in the name of containing jihad; the Hindutva fundamentalists organise pogroms in revenge for events that are alleged to have taken place a thousand years ago; and the Israeli state engages in daily rites of slaughter to defend a homeland secured by the expropriation of a territory and the expulsion of its people.

It is instructive that Waseem breaks the solemnity of her portraits by inserting them within a comic-strip narrative of violence and retribution. The drama unfolds through energetic play mirrored in a portfolio of small works which the artist has composed as a gallery of rogues based on characters from Italian baroque theatre.

Individual as their quests are the neo-miniaturists, united by certain tendencies: their works flirt with the viewer, who participates as fully as the artist in the process of activating meaning. Rejoicing in paradox and interactivity, these artworks draw on an intriguing gamut of concerns and formal techniques. They draw narratives from popular culture and cosmology, autobiography and shamanistic ritual, the artifacts of daily life and the formulae of magic.

In this panoply of hybrid signs, we may discern the directions that artists will take in this century. Certain features are clear: for one, our younger artists have chosen quite deliberately to de-classicise the practice of art through the creation of new vernaculars; by projecting themselves through such eclectic strategies, they lay an insistent if imperious claim upon the viewer’s attention.

And yet, they are reluctant Duchampists, balancing precariously on the seesaw between artistic convention and ‘viewerly’ feeling. While they wish to project images that have a sensuous appeal to a wide audience, they are also tempted to tease the viewer, to employ techniques of evasion and surprise; they desire, simultaneously, to console and shock their parent culture.