The Gandhi-Bacha combine is a role model for all of us to emulate for achieving a more tolerant and peaceful society

For a decade now, violence from within remains the biggest security challenge in Pakistan. Enmeshed primarily in religion, the killing frenzy is deeply embedded in socio economic and political factors. Seen through democratic lens, ends sought are not problematic as such as is often the case with means pursued. For Gandhi, the quest for truth, being the sacrosanct objective of life, necessitates the sacred means of nonviolence. A peaceful Pakistan is well set to be at peace with itself, its neighbours and the world at large.

On October 2 every year, world celebrates international nonviolence day in commemoration of Mahatma Gandhi’s (1869-1948) peaceful struggle against the British colonial rule in India. For Mohandas K. Gandhi, "ahimsa" or nonviolence was a means to an end, the truth. The two were so inextricably linked that hardly one can exist without other. The truth is God, its proximity and service to humanity without any materialistic calculations. Although we have no control over truth--they were, are and will be the same--we can control of the means. The only means to truth is nonviolence.

Mahatma conceded that treading nonviolent path was invariably a difficult task. The truth in Gandhi’s life time was the struggle for Indian independence against the British yoke. Nonviolence was the noblest means he adopted to that end. It was never a passive resistance but a passionate struggle. It took the forms of civil disobedience, non-cooperation and the likes of fasting and peaceful protests. Goals through nonviolent means were not an idealistic utopia.

Besides Indian independence, Gandhi’s innumerable experiences of the mundane life had vindicated this before him. The search for truth was bereft of violent means. "There are many causes that I am prepared to die for but no causes that I am prepared to kill for," said Gandhi.

Gandhi was averse to exclusion. Indian nationalism much like any other nationalism was a stepping stone to internationalism. Gandhi conceived of independent India as a role model of nonviolence for the rest of the world to emulate. Not nationalism but exploitation was a bane.

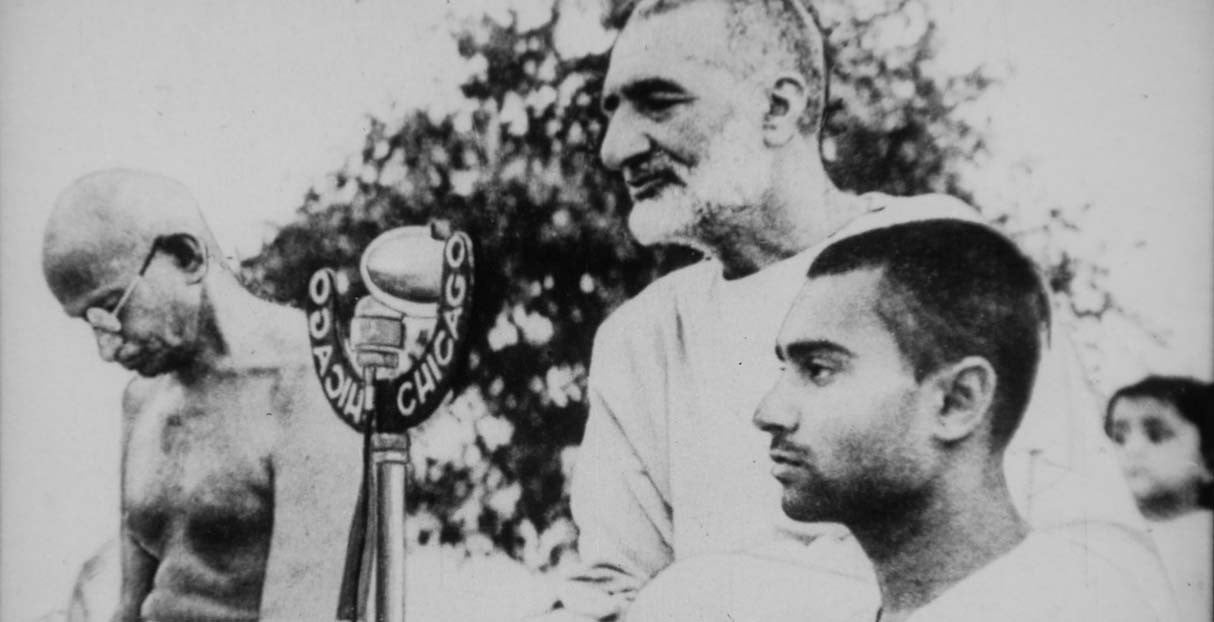

If Gandhi was the apostle of nonviolence on the all India level, he had a paragon of his philosophy in the Indian North West Frontier Province. Abdul Ghaffar Khan aka Bacha Khan (1889-1986) had a huge responsibility to discharge. Also known as "frontier Gandhi" for his avowed belief in nonviolence, the Pakhtun reformer preached ahinsa in a volatile region.

His socio political reforms among the Pakhtuns were the best incarnation of the man’s nonviolent and progressive views. Imparting religious and secular education was his first target.

In 1910, along with Haji Fazli Wahid popularly known as Haji Turangzai, Bacha Khan opened an educational institute called Darul Ulum at Utmanzai and Gaddar in Mardan. On April 1921, he established Anjuman-i-Islah-ul-Afaghana (Society for the Reformation of Afghans) meant for eradicating social evils, promotion of Pashto literature and inculcating ‘real love’ for Islam.

On 10 April 1921, he inaugurated Azad Islamia Madrassah at Utmanzi. Dozens more were established in other parts of the Pakhtun North West. The curriculum comprised the Holy Quran, Hadith, Fiqah, Pashto, Mathematics, English and Arabic.

Bacha Khan and his elder brother Dr Khan were the first to admit their children in madrassah. The education was free and enrolled students irrespective of caste and even religion. In 1926, Bacha Khan performed Haj. In May 1928, he issued the first publication of monthly magazine entitled Pakhtun.

On September 1, 1929, Bacha Khan founded Zalmojirga (council of youths). Two pre requisites to joining the council were being literate and the pledge of shunning communalism. In order to guide the vast majority of illiterate and the elderly, in November 1929, Bacha Khan formed Khudai Khidmatgars (servants of God). The two organisations were anchored in the eradication of social evils from the Pakhtun society and getting rid of British colonialism. High ethical ethos was the hallmark of joining the KK. The aspirants pledged to strictly adhere to nonviolence, shun family feuds and among others refrain from intoxicants.

Bacha Khan invoked religion while inculcating nonviolence and forbearance. He would quote to people how the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and his companions tolerated the worst kind of repression with great patience. On 23 April, KK joined the Gandhi’s civil disobedience movement launched in April 1930.

The colonial government’s shooting of the unarmed demonstrators in Qissa Khwani Bazar Peshawar killed 200 members of KK. Bacha Khan was nabbed and sentenced to three years punishment. On 31 May, the police firing caused 12 fatalities on a similar gathering in Peshawar.

On 24 August, in Bannu the police shot to death 72 people. Resultantly, KK and ZalmoJirga were proscribed. Within a couple of months, the KK’s membership swelled from 1200 to 25,000. On 30 March 1931, Bacha Khan announced his association with the AINC while retaining KK’s separate identity. By 1947, as an independence fighter, Ghaffar Khan had languished 14 years in prison for leading his red-shirted followers in nonviolent protests against the Raj.

At the time of partition, Bacha Khan nurtured the dream of an independent Pakhtunistan state. Since that was not entertained, Ghaffar Khan reformulated the Pakhtunistan demand as a demand for provincial autonomy within Pakistani state.

In the first week of September 1947, KK pledged its loyalty to Pakistan. On 23 February 1948, as member of Constituent Assembly, Bacha Khan formally swore his allegiance to Pakistan. As a goodwill gesture, Jinnah invited him for meal. On the invitation of Bacha Khan, in April 1948, Jinnah met the former in Peshawar.

Jinnah invited Bacha Khan to join Muslim League, which the latter politely declined. A man of impeccable integrity, Bacha Khan accused Chief Minister Abdul Qayyum of creating misunderstanding between him and Jinnah.

After independence, successive governments in Pakistan jailed him. Last time he was jailed in 1972 and set free in 1976. In all, Bacha Khan spent 47 years either in prison or exile. Aged 98, Bacha khan breathed his last on 20 January 1988.

Perhaps at no time of our history did we need non-violence as a way of life as we desperately need it today. Politically motivated violence has claimed the lives of more than 45,000 people. One may disagree with Gandhi and Bacha Khan’s objectives but may never question their full devotion to nonviolence.

In our capacities as the proud citizens of Pakistan, we all have the right to cherish goals how unacceptable they may appear to others. The duo’s demand for independence was never acceptable to the colonial Britain. What we all need indisputably is to pursue our goals in a nonviolent fashion.

The Gandhi-Bacha combine is a role model for all of us to emulate. For that to happen, we genuinely need to revisit our syllabi. In the wake of 18th Amendment, with education becoming a provincial subject, provinces have the privilege to change the syllabi.