A comparison of textbooks taught in India and Pakistan has enabled The History Project to raise questions that challenge the narrow historical narrative created on both sides of the border

What would you call it -- the independence of Pakistan or the partition of India? This choice of words, the manner in which we describe history, is largely dependent on which side of the border we stand on.

The events of 1947 were brutal and violent at the end, leaving bitterness on both sides, which seeped into our historical narrative. As a result, we told only one side of the story, and we distorted it to guise ourselves as martyrs at one point and victors at another. We justified our own existence by dehumanising the other.

The History Project began informally around 13 years ago at a conflict resolution camp organised by the Seeds of Peace, an organisation that brings together teenagers from conflict regions. It was here that Qasim Aslam, co-founder of the project saw and felt, first-hand, the damage that historical biases can wreak on the peace-building process, especially between India and Pakistan.

"Without taking sides, keeping our personal biases or statements of facts as far at bay as possible, we’re juxtaposing the contrasting narratives to highlight the differences, to showcase that suffering is a shared phenomenon and there is always another side to every story. To give insights to our younger generations on why the other side thinks the way they do, and how that might be the root of why we all behave the way we do," says Qasim Aslam.

The History Project aims to raise questions that will challenge the narrow historical narrative created on both sides. The last book that was launched on April 20, 2013 in Mumbai, looked at the events leading up to the partition. And, on introducing it in schools, they got the response they were looking for.

Barkat ul Nisa Kamili, an editor with The History Project from the Indian side, says, "it has actually helped in shedding many biases and preconceived notions that I had."

Since resources were scarce, the first book was launched in only a handful of schools on both sides of the border.

Lavanaya Julaniya, another editor from Delhi joined the team shortly before the launch of the first book, remembers clearly some of the reactions they got. "In workshops, we had this game in which the students had to come up with all possible words when we threw a few names around," she says.

She recalls the reaction of Indian students when asked about Jinnah. One student responded by saying, "evil, horrible, traitor, Voldemort". When asked about partition, the students said, "we were one nation, yet we are separated", "shouldn’t have happened", "uncalled for", "could have been avoided", "loss", "bloodshed", "tragedy".

But when we threw the same words around to their Pakistani counterparts, the partition meant, "happiness", "jubilation", "victory", "freedom from not just British but Hindus as well".

The History Project is working on a new book to continue to challenge this mindset.

Julaniya talks about the Young India Fellowship (YIF) she was attending in New Delhi when she thought of starting work on the second book. "As part of the rigorous schedule of YIF, we had to work on client projects with a team of three fellows. When the list of project was emailed to us, an idea struck me -- how about I start writing the second book of The History Project?"

And, so began the skype calls, the long winding emails and endless discussions between Qasim Aslam and Ayyaz Ahmad, the original masterminds behind The History Project, and the Indian team consisting of Lavanya Jhulania, Anil K. George and Barkat ul Nisa Kamili.

The book focuses on six personalities: Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Iqbal and Tilak.

Initially, there was a lot of debate about the sixth personality -- whether to choose Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Abul Kalam Azad, B.R. Ambedkar or Sardar Patel over Tilak. But the team made the final cut, taking into account the importance each personality was given in the history books from both sides and also the controversial way in which the role of some of these personalities is discussed.

The second edition will give a detailed account of the way one leader is remembered on both sides. For instance, Indian textbooks from grades 6 to 10 traditionally define Gandhi’s role in the non-cooperation movement of the 1920s as, "Gandhi ji put forward the programme of action which was to proceed in stages. The movement was a great success. Gandhi, Tagore, Subramaniya Aiyar, Jamnalal Bajaj and many distinguished Indians renounced their titles and honours conferred upon them by the British. Gandhi ji gave up the title of ‘Kaiser-e-Hind’."

Pakistani textbooks, ranging from grade 6 to 10, on the other hand, present an entirely different perspective -- "Gandhi being a shrewd politician had planned to use the Khilafat agitation to pressurise the government to come to terms for Indian Independence from British Rule. Whether the Muslims won or lost on Khilafat issue was immaterial to Gandhi, what mattered was the purpose the movement could be made to serve."

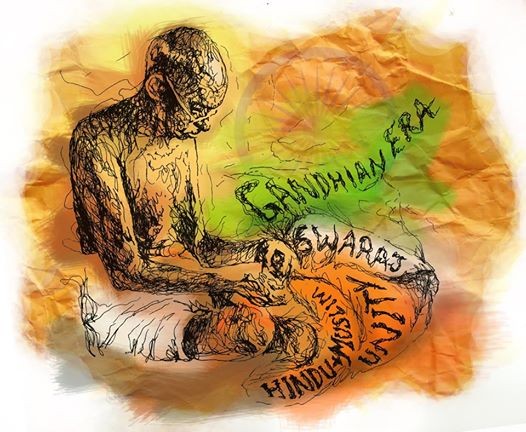

This book, like the previous one, also relies on carefully constructed images to help get the message across. "The graphical illustrations will accompany each chapter, perhaps, increase in frequency. In order to make the book more tangible for teachers, we’re introducing in-page thought boxes. Without trying to directly call upon biases or introducing our own opinions, we’re asking questions that will encourage children to think on the source of certain excerpts," Aslam explains some of the changes they are making this time.

At times the questions asked are the same: In one line -- tell us why ‘Satyagraha’ was the term used for Gandhi’s political activism? Because the definitions differ.

Aslam explains, "We aren’t picking sides. What we want is for the children to, firstly, know that there is always another side to every story and, secondly, question narratives before they assimilate them as a set of facts. And I think our unique approach is achieving that."

The Project is truly unique since it has dispelled a lot of historical misconceptions among the team as well. By putting together the discussion of the partition from both sides they have been able to forgo the biases and understanding of history that they grew up with. "I contributed towards Gandhi and Iqbal in the second book," says Kamili, "After having read the Pakistani textbooks and knowing the personalities through their lens, I sometimes think the partition of subcontinent could have been avoided. Maybe Gandhi was not completely a supporter of Hindu-Muslim unity. Maybe Jinnah was forced to consider the partition as the only solution. We are taught History in black and white but it actually exists in shades of grey."

The team is aiming to release the next book sometime in mid-2015 and is currently trying to raise funds for it. They are using various platforms that make use of crowd funding - a concept that allows independent individuals to put money in a project they feel is worthwhile. And this project should definitely top the list.

To fund the project log on to igg.me/at/thehistoryproject