As the political contest has been largely personalised, political speech is being drained of elementary decency

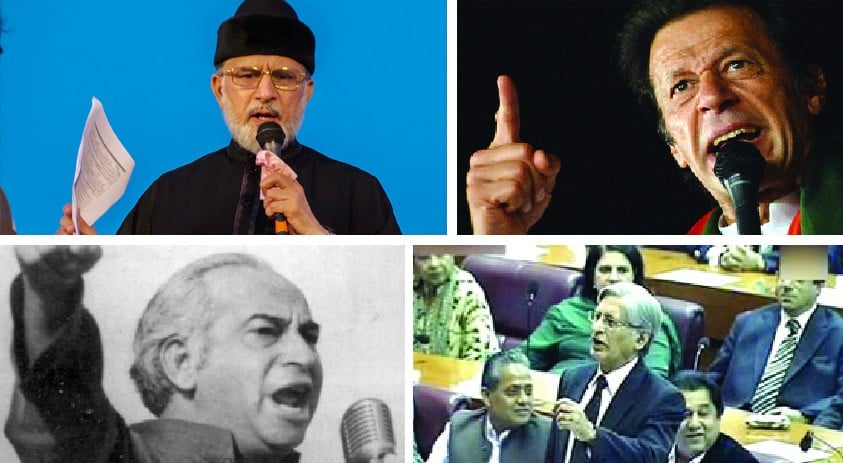

If Pakistan’s politics has suffered for want of a rational, democratic idiom of expression the deficiency has been greatly aggravated during the current Imran/Qadri-government confrontation.

That Imran and Qadri have developed the container as a new version of the palace balcony, the Kremlin Wall, the Nazi rostrum, the Red Fort or the high dais at Mochi Gate, from where the custodians of power have been speaking down to their subjects, is understandable.

This stage puts them much higher than hamashuma and gives them the same feeling of superiority over the wretched of the earth that people driving along elevated motorways derive from their advantage over people occupying house at a lower level.

This is understandable because despite all the hullabaloo about bad governance the new challengers have not questioned the basic assumptions of a coercive state. They only promise to treat the subjects somewhat better than they have so far been. Which matters but not much.

On one of the vehicles used in the marches one saw a banner bearing the couplet:

Perhaps the idea was to proclaim that the man in the container possessed all the attributes of a leader of the faithful Allama Iqbal had identified. It is debatable if capturing state power is the highest objective possible (nigeh buland) for an enlightened human being, and there is no means of ascertaining the capacity to feel human anguish (jan pur-soze) in the march commander’s heart, but the speech that puts balm on lacerated hearts (sukhan dil-nawaz) has been little in evidence.

On the contrary, political speech is being drained of elementary decency.

The political contest has been largely personalised. The dominant refrain is that the other fellow is an incompetent ruler, a heartless manager and an incorrigible thief and ‘I’ am the opposite. Such total reliance on demonisation of the other betrays political immaturity and goads an unsuspecting public into passing ex-parte judgment on the other without examining the alternatives the challengers are offering, assuming that they have clearly thought-out alternatives.

Pakistanis should be aware of the pitfalls on this path. More than once they have made the mistake of accepting the denunciation of governments (of politicians) by coup-makers without looking into the latter’s baggage. Thus, personalised and vitriolic rhetoric to which the people have been subjected for weeks has not been a source of edification; instead it has degraded political discourse.

Contrary to the universal practice, which is also reflected in the subcontinent’s tradition, whereby political decisions are expressed in the name of the collective, our politicians have become obsessed with ‘I’. The complexes of Maulana Qadri become clear the moment he assumes the title of Sheikh-ul-Islam. Imran Khan has never shared the glory of winning the World Cup, or building the Shaukat Khanum Hospital or nurturing Tehreek-e-Insaf with his team. But one was appalled to hear too much of "I" on the other side too.

When politicians of decades-old standing give long lectures on their personal achievements, which should have been known to the people, they unnecessarily challenge the latter’s right and capacity to judge what the various actors have done. This extra-generous use of "I" in political harangues lays the foundation of personality cults that are totally incompatible with democratic politics or any thinking based on reason.

The politics of resistance does admit the need to tear off the mask of power and righteousness all oppressive authorities use. The heroes of the sub-continent’s terrorist movement recognised the need to rid the people of their fear of the empire and awaken their will to fight for freedom. Mandela had to do the same. But the targets of freedom fighters were the systems of oppression and not the members of the ruling race or group.

In today’s Pakistan it is not necessary to drown the government or its representatives in a sea of scorn and contempt. The people are not afraid of taking the government to task. The media has been doing this all the time, especially since Gen. Musharraf’s abdication. Public associations do not spare the authorities either. Those who are not organised are attacking electricity suppliers and police posts.

In this situation calling political rivals’ names (which is being done by both sides) and ridiculing them reinforces the view that this is all that politics is about. The possibility of raising the level of debate to issues of governance is closed.

It is important for the development of healthy politics that politicians respect one another regardless of their differences and rivalries. Unfortunately we have had some questionable precedents -- such as the Quaid-i-Azam calling Abul Kalam Congress Showboy or attempts by Liaquat Ali Khan, Ghulam Mohammad and Iskander Mirza to malign their political rivals or Bhutto giving his opponents derogatory appellations, but these references need to be forgotten.

There is something to be learnt from the states’ tradition of addressing one another with a prologue of courtesy. Lawyers appearing in courts call the opposing counsel learned friends (even though a Suhrawardy may turn around and declare that his adversary is neither learned nor a friend). The police have power to arrest a criminal but no right to violate his dignity of person.

Apart from the question of mutual respect that must subsist between two adversaries in any arena, what is involved is the prestige of the forum. The respect members of the colonial period assemblies paid one another or lawyers show to each other actually amounts to respecting assemblies/courts. The need to target fellow parliamentarians in a manner that the institution of parliament is not maligned can in no circumstance be ignored.

After all wit can be used (by anyone possessing it) to chide a political animal, like Aitzaz Ahsan did with the help of an allegorical tale.

An expression bandied about rather thoughtlessly is ‘change’. Now, the people are more convinced of the need for change than the present chorus leaders. You hold a referendum and anyone voting against change will be denounced as an irredeemable idiot. But what change? Changing a system that is rooted in an exploitative social order and has become part of the people’s habit is no push-button affair.

Uprooting a system without the availability of enforceable alternatives will only lead to chaos. Thus, the contours of a progressive change must first be spelt out by social and political scientists and the people invited to own them, through an open debate, before they can be handed over to legislators.

This is not happening. No political outfit can claim to have developed a national thesis, that is, a thesis that meets the aspirations of all national units and various communities. In such a situation the call for change is quite misleading and when a new line-up of rulers will be presented as change, the people will feel frustrated no end.

The symbols used for ‘change’ may be noted, such as ‘Tsunami’ and ‘passion’. The former denotes an irresistible force and the latter an extraordinary commitment to achieve a goal. All political movements need mass support and a determined cadre. But force and passion divorced from reason and public weal can only cause upheavals instead of a people-friendly turn of events.

All political events offer lessons -- good or bad -- to the people and there will be time to count the plus and minus of the contribution to the politics of Pakistan made during the present agitation but neither side will be able to claim having improved the idiom of political discourse.